Molecular imaging

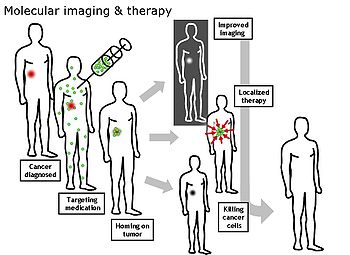

The ultimate goal of molecular imaging is to be able to noninvasively monitor all of the biochemical processes occurring inside an organism in real time.

Current research in molecular imaging involves cellular/molecular biology, chemistry, and medical physics, and is focused on: 1) developing imaging methods to detect previously undetectable types of molecules, 2) expanding the number and types of contrast agents available, and 3) developing functional contrast agents that provide information about the various activities that cells and tissues perform in both health and disease.

This ability to image fine molecular changes opens up an incredible number of exciting possibilities for medical application, including early detection and treatment of disease and basic pharmaceutical development.

Furthermore, molecular imaging allows for quantitative tests, imparting a greater degree of objectivity to the study of these areas.

Organizations such as the SNMMI Center for Molecular Imaging Innovation and Translation (CMIIT) have formed to support research in this field.

For example, at 1.5 Tesla, a typical field strength for clinical MRI, the difference between high and low energy states is approximately 9 molecules per 2 million.

To date, many studies have been devoted to developing targeted-MRI contrast agents to achieve molecular imaging by MRI.

[2] In particular, the recent development of micron-sized particles of iron oxide (MPIO) allowed to reach unprecedented levels of sensitivity to detect proteins expressed by arteries and veins.

[citation needed] The downside of optical imaging is the lack of penetration depth, especially when working at visible wavelengths.

Because the absorption coefficient of tissue is considerably lower in the near infrared (NIR) region (700-900 nm), light can penetrate more deeply, to depths of several centimeters.

Some researchers have applied NIR imaging in rat model of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), using a peptide probe that can binds to apoptotic and necrotic cells.

Quantum dots, with their photostability and bright emissions, have generated a great deal of interest; however, their size precludes efficient clearance from the circulatory and renal systems while exhibiting long-term toxicity.

It has been shown to be valuable for diagnostic inhalation studies for the evaluation of pulmonary function; for imaging the lungs; and may also be used to assess rCBF.

Detection of this gas occurs via a gamma camera—which is a scintillation detector consisting of a collimator, a NaI crystal, and a set of photomultiplier tubes.

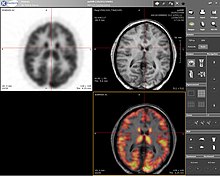

By rotating the gamma camera around the patient, a three-dimensional image of the distribution of the radiotracer can be obtained by employing filtered back projection or other tomographic techniques.

Additionally, due to the radioactivity of the contrast agent, there are safety aspects concerning the administration of radioisotopes to the subject, especially for serial studies.