Currency

[1][2] A more general definition is that a currency is a system of money in common use within a specific environment over time, especially for people in a nation state.

[3] Under this definition, the British Pound sterling (£), euros (€), Japanese yen (¥), and U.S. dollars (US$) are examples of (government-issued) fiat currencies.

[5] Digital currencies that are not issued by a government monetary authority, such as cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, are different because their value is market-dependent and has no safety net.

Various countries have expressed concern about the opportunities that cryptocurrencies create for illegal activities such as scams, ransomware (extortion), money laundering and terrorism.

By the late Bronze Age, however, a series of treaties had established safe passage for merchants around the Eastern Mediterranean, spreading from Minoan Crete and Mycenae in the northwest to Elam and Bahrain in the southeast.

It is thought that the increase in piracy and raiding associated with the Bronze Age collapse, possibly produced by the Peoples of the Sea, brought the trading system of oxhide ingots to an end.

It was only the recovery of Phoenician trade in the 10th and 9th centuries BC that led to a return to prosperity, and the appearance of real coinage, possibly first in Anatolia with Croesus of Lydia and subsequently with the Greeks and Persians.

Most major economies using coinage had several tiers of coins of different values, made of copper, silver, and gold.

Gold coins were the most valuable and were used for large purchases, payment of the military, and backing of state activities.

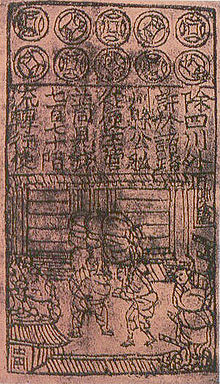

In premodern China, the need for lending and for a medium of exchange that was less physically cumbersome than large numbers of copper coins led to the introduction of paper money, i.e. banknotes.

It began as a means for merchants to exchange heavy coinage for receipts of deposit issued as promissory notes by wholesalers' shops.

In the 10th century, the Song dynasty government began to circulate these notes amongst the traders in its monopolized salt industry.

At around the same time in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the 7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar).

Innovations introduced by Muslim economists, traders and merchants include the earliest uses of credit,[8] cheques, promissory notes,[9] savings accounts, transaction accounts, loaning, trusts, exchange rates, the transfer of credit and debt,[10] and banking institutions for loans and deposits.

[10] In Europe, paper currency was first introduced on a regular basis in Sweden in 1661 (although Washington Irving records an earlier emergency use of it, by the Spanish in a siege during the Conquest of Granada).

By 1900, most of the industrializing nations were on some form of gold standard, with paper notes and silver coins constituting the circulating medium.

Private banks and governments across the world followed Gresham's law: keeping the gold and silver they received but paying out in notes.

Banknotes were initially mostly paper, but Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation developed a polymer currency in the 1980s; it went into circulation on the nation's bicentenary in 1988.

As of 2016,[update] polymer currency is used in over 20 countries (over 40 if counting commemorative issues),[12] and dramatically increases the life span of banknotes and reduces counterfeiting.

In 1978 the International Organization for Standardization published a system of three-digit alphabetic codes (ISO 4217) to denote currencies.

For example, Article I, section 8, clause 5 of the United States Constitution delegates to Congress the power to coin money and to regulate the value thereof.

This power was delegated to Congress in order to establish and preserve a uniform standard of value and to insure a singular monetary system for all purchases and debts in the United States, public and private.

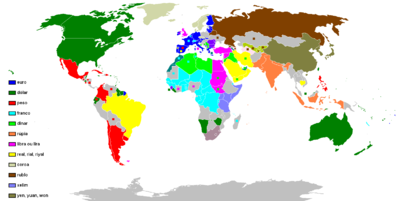

Several countries can use the same name for their own separate currencies (for example, a dollar in Australia, Canada, and the United States).

The large number of international tourists and overseas students has resulted in the flow of services and goods at home and abroad.

It also represents that the competitiveness of global goods and services directly affects the change of international exchange rates.

The impact of monetary policy on the total amount and yield of money directly determines the changes in the international exchange rate.

Such policies determine the mechanism of linking domestic and foreign currencies and therefore have a significant impact on the generation of exchange rates.

In addition, the government should use macro policies to make mature adjustments to deal with the impact of currency exchange on the economy.

The exchange rate of freely convertible currency is too high or too low, which can easily trigger speculation and undermine the stability of macroeconomic and financial markets.

Opponents of this concept argue that local currency creates a barrier that can interfere with economies of scale and comparative advantage and that in some cases they can serve as a means of tax evasion.