Money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context.

[1][2][3] The primary functions which distinguish money are: medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and sometimes, a standard of deferred payment.

[4] Its value is consequently derived by social convention, having been declared by a government or regulatory entity to be legal tender; that is, it must be accepted as a form of payment within the boundaries of the country, for "all debts, public and private", in the case of the United States dollar.

[6] The use of barter-like methods may date back to at least 100,000 years ago, though there is no evidence of a society or economy that relied primarily on barter.

[citation needed] This occurred because gold and silver merchants or banks would issue receipts to their depositors, redeemable for the commodity money deposited.

In the 13th century, paper money became known in Europe through the accounts of travellers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck.

[17] Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made Into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country.

After World War II and the Bretton Woods Conference, most countries adopted fiat currencies that were fixed to the U.S. dollar.

[4][22][23] There have been many historical disputes regarding the combination of money's functions, some arguing that they need more separation and that a single unit is insufficient to deal with them all.

Having a medium of exchange can alleviate this issue because the former can have the freedom to spend time on other items, instead of being burdened to only serve the needs of the latter.

Also known as a "measure" or "standard" of relative worth and deferred payment, a unit of account is a necessary prerequisite for the formulation of commercial agreements that involve debt.

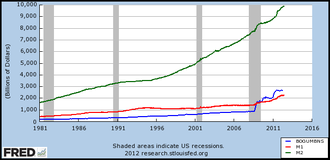

In other words, the money supply is the number of financial instruments within a specific economy available for purchasing goods or services.

Many items have been used as commodity money such as naturally scarce precious metals, conch shells, barley, beads, etc., as well as many other things that are thought of as having value.

[32] Examples of commodities that have been used as mediums of exchange include gold, silver, copper, rice, Wampum, salt, peppercorns, large stones, decorated belts, shells, alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis, candy, etc.

[34][38] Fiat money, if physically represented in the form of currency (paper or coins), can be accidentally damaged or destroyed.

In Europe, this system worked through the medieval period because there was virtually no new gold, silver, or copper introduced through mining or conquest.

In premodern China, the need for credit and for circulating a medium that was less of a burden than exchanging thousands of copper coins led to the introduction of paper money.

In the 10th century, the Song dynasty government began circulating these notes amongst the traders in their monopolized salt industry.

At around the same time in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the 7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar).

Innovations introduced by economists, traders and merchants of the Muslim world include the earliest uses of credit,[40] cheques, savings accounts, transactional accounts, loaning, trusts, exchange rates, the transfer of credit and debt,[41] and banking institutions for loans and deposits.

By 1900, most of the industrializing nations were on some form of a gold standard, with paper notes and silver coins constituting the circulating medium.

Private banks and governments across the world followed Gresham's law: keeping gold and silver paid but paying out in notes.

Commercial bank money or demand deposits are claims against financial institutions that can be used for the purchase of goods and services.

[43] Commercial bank money differs from commodity and fiat money in two ways: firstly it is non-physical, as its existence is only reflected in the account ledgers of banks and other financial institutions, and secondly, there is some element of risk that the claim will not be fulfilled if the financial institution becomes insolvent.

The stability of the demand for money prior to the 1980s was a key finding of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz[56] supported by the work of David Laidler,[57] and many others.

That is, when buying a good, a person is more likely to pass on less-desirable items that qualify as "money" and hold on to more valuable ones.

[60] Historically, objects that were difficult to counterfeit (e.g. shells, rare stones, precious metals) were often chosen as money.

[61] Before the introduction of paper money, the most prevalent method of counterfeiting involved mixing base metals with pure gold or silver.

Today some of the finest counterfeit banknotes are called Superdollars because of their high quality and likeness to the real U.S. dollar.

However, in several legal and regulatory systems the term money laundering has become conflated with other forms of financial crime, and sometimes used more generally to include misuse of the financial system (involving things such as securities, digital currencies, credit cards, and traditional currency), including terrorism financing, tax evasion, and evading of international sanctions.