Monumental sculpture

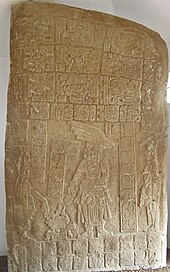

The term is also used to describe sculpture that is architectural in function, especially if used to create or form part of a monument of some sort, and therefore capitals and reliefs attached to buildings will be included, even if small in size.

It is only in wealthy societies that the possibility of creating sculptures that are large but merely decorative really exists (at least in long-lived materials such as stone), so for most of art history the different senses of the term cause no difficulties.

The ability to summon the resources to create monumental sculpture, by transporting usually very heavy materials and arranging for the payment of what are usually regarded as full-time sculptors, is considered a mark of a relatively advanced culture in terms of social organization.

[8] Some undoubtedly advanced cultures, such as the Indus Valley civilization, appear to have had no monumental sculpture at all, though producing very sophisticated figurines and seals.

Byzantine art, which had largely avoided the societal collapse in the Western Roman Empire, never resumed the use of monumental figurative sculpture, whether in religious or secular contexts, and was to ban even two-dimensional religious art for a period in the Byzantine iconoclasm.

"Monumental sculpture" is still used within the stoneworking and funeral trades to cover all forms of grave headstones and other funerary art, regardless of size.

[9] Sculptures covered by the term in modern art are likely to be over two metres in at least one dimension, and sufficiently large not to need a high plinth, though they may have one.