William Morris

After university, he married Jane Burden, and developed close friendships with Pre-Raphaelite artists Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti and with Neo-Gothic architect Philip Webb.

[8] He took an interest in fishing with his brothers as well as gardening in the Hall's grounds,[9] and spent much time exploring the Forest, where he was fascinated both by the Iron Age earthworks at Loughton Camp and Ambresbury Banks and by the Early Modern Hunting Lodge at Chingford.

[13] Aged 9, he was then sent to Misses Arundale's Academy for Young Gentlemen, a nearby preparatory school; although initially riding there by pony each day, he later began boarding, intensely disliking the experience.

[27] Through Burne-Jones, Morris joined a group of undergraduates from Birmingham who were studying at Pembroke College: William Fulford (1831–1882), Richard Watson Dixon, Charles Faulkner, and Cormell Price.

[30] Morris was heavily influenced by the writings of the art critic John Ruskin, being particularly inspired by his chapter "On the Nature of Gothic Architecture" in the second volume of The Stones of Venice; he later described it as "one of the very few necessary and inevitable utterances of the century".

Funded mainly by Morris, who briefly served as editor and heavily contributed to it with his own stories, poems, reviews and articles, the magazine lasted for twelve issues, and garnered praise from Tennyson and Ruskin.

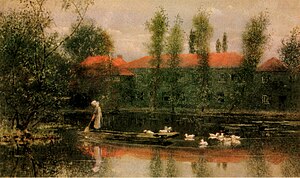

[46] William Morris became increasingly fascinated with the idyllic Medievalist depictions of rural life which appeared in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, and spent large sums of money purchasing such artworks.

[54] They were married in a low-key ceremony held at St Michael at the North Gate church in Oxford on 26 April 1859, before honeymooning in Bruges, Belgium, and settling temporarily at 41 Great Ormond Street, London.

[64] They aided him in painting murals on the furniture, walls, and ceilings, much of it based on Arthurian tales, the Trojan War, and Geoffrey Chaucer's stories, while he also designed floral embroideries for the rooms.

[71] Their stained glass windows proved a particular success in the firm's early years as they were in high demand for the surge in the Neo-Gothic construction and refurbishment of churches, many of which were commissioned by the architect George Frederick Bodley.

[98] In August 1867 the Morrises holidayed in Southwold, Suffolk,[99] while in the summer of 1869 Morris took his wife to Bad Ems in Rhineland-Palatinate, central Germany, where it was hoped that the local health waters would aid her ailments.

[117] His two visits to the country profoundly influenced him, in particular in his growing leftist opinions; he would comment that these trips made him realise that "the most grinding poverty is a trifling evil compared with the inequality of classes.

"[118] Morris and Burne-Jones then spent time with one of the Firm's patrons, the wealthy George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle and his wife Rosalind, at their Medieval home in Naworth Castle, Cumberland.

[123] Now in complete control of the Firm, Morris took an increased interest in the process of textile dyeing and entered into a co-operative agreement with Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer who operated the Hencroft Works in Leek, Staffordshire.

[129] The Firm was obtaining increasing numbers of commissions from aristocrats, wealthy industrialists, and provincial entrepreneurs, with Morris furnishing parts of St James's Palace and the chapel at Eaton Hall.

[130] As a result of his growing sympathy for the working-classes and poor, Morris felt personally conflicted in serving the interests of these individuals, privately describing it as "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich".

[147] Turning SPAB's attention abroad, in Autumn 1879 Morris launched a campaign to protect St Mark's Basilica in Venice from restoration, garnering a petition with 2000 signatures, among whom were Disraeli, Gladstone, and Ruskin.

[153] Morris described his mixed feelings toward his deceased friend by stating that he had "some of the very greatest qualities of genius, most of them indeed; what a great man he would have been but for the arrogant misanthropy which marred his work, and killed him before his time".

[161] In November 1883 he was invited to speak at University College, Oxford, on the subject of "Democracy and Art" and there began espousing socialism; this shocked and embarrassed many members of staff, earning national press coverage.

[186] The Black Monday riots of February 1886 led to increased political repression against left-wing agitators, and in July Morris was again arrested and fined for public obstruction while preaching socialism on the streets.

First published in February 1885, it would contain contributions from such prominent socialists as Engels, Shaw, Paul Lafargue, Wilhelm Liebknecht, and Karl Kautsky, with Morris also regularly writing articles and poems for it.

Set in Kent during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, it contained strong socialist themes, although it proved popular among those of different ideological viewpoints, resulting in its publication in book form by Reeves and Turner in 1888.

[193] Combining utopian socialism and soft science fiction, the book tells the tale of a contemporary socialist, William Guest, who falls asleep and awakens in the early 21st century, discovering a future society based on common ownership and democratic control of the means of production.

"[211] In December 1895 he gave his final open-air talk at Stepniak's funeral, where he spoke alongside the socialist Eleanor Marx, trade unionist Keir Hardie, and anarchist Errico Malatesta.

"[34] In December 1888, the Chiswick Press published Morris's The House of the Wolfings, a fantasy story set in Iron Age Europe which provides a reconstructed portrait of the lives of Germanic-speaking Gothic tribes.

[223] In July 1896, Morris went on a cruise to Norway with construction engineer John Carruthers, during which he visited Vadsø and Trondheim; during the trip his physical condition deteriorated and he began experiencing hallucinations.

The Wood Beyond the World is considered to have heavily influenced C. S. Lewis's Narnia series, while J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired by Morris's reconstructions of early Germanic life in The House of the Wolfings and The Roots of the Mountains.

[265] During his lifetime, Morris produced items in a range of crafts, mainly those to do with furnishing,[266] including over 600 designs for wall-paper, textiles, and embroideries, over 150 for stained glass windows, three typefaces, and around 650 borders and ornamentations for the Kelmscott Press.

[254][279] Morris's patterns for woven textiles, some of which were also machine made under ordinary commercial conditions, included intricate double-woven furnishing fabrics in which two sets of warps and wefts are interlinked to create complex gradations of colour and texture.

[303] The collection includes books, embroideries, tapestries, fabrics, wallpapers, drawings and sketches, furniture and stained glass, and forms the focus of two published works (produced to accompany special exhibitions).