White War

Extending southwards towards the River Po, it potentially allowed Austro-Hungarian forces to strike towards the lower Adige and Mincio, cutting off Veneto and Friuli-Venezia from the rest of Italy.

In practical terms however, the road and rail systems did not allow the Italian commander Luigi Cadorna to mass his forces here, so instead he concentrated on the Isonzo front further east, where he hoped to make a decisive breakthrough.

[7]: 63 The 4th Army was deployed on the Dolomites sector under General Luigi Nava, based in Vittorio Veneto, which its forces from the Cereda Pass to Mount Peralba, over about 75 km as the crow flies, and about double the distance on the ground.

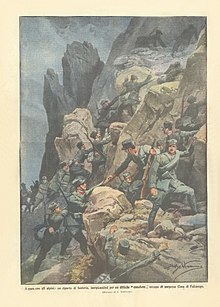

By spreading their guns over isolated positions on the slopes and peaks, the Austrians exploited the Dolomite terrain very effectively, securing every possible advantage in an attempt to confine the Italians to the lower valleys and prevent them from accessing the strategic passes.

[10]: 33 Their guns were moved to more favourable positions less detectable by the enemy; the buildings were highly visible and at times the Austro-Hungarians continued to pretend that they were occupied in order to divert Italian fire towards useless targets.

[12]: 41 In Cortina the gendarmes, the financial police, the few Standschützen present and the elderly or veterans repatriated for illness or injuries, retreated behind Som Pouses to reinforce the defences that closed the Conca to the north.

Although he had declared taking the Conca d'Ampezzo as his priority, General Nava, worried about strong resistance and ambushes from the woods, delayed in issuing orders, advising the commanders of the army corps to operate with great caution; so May 24 passed quietly.

The last winter of the war also coincided with the hardest period for the civilian population, with the terrible food shortage that hit the Habsburg Empire, compelling the Austro-Hungarian troops to seize the few provisions the inhabitants had in occupied places.

[12]: 46 The action planned by the Italian command anticipated attacking the Austrian defences with three assault columns, supported by field artillery and batteries of howitzers, 149mm guns and 210mm mortars placed on the hills surrounding Cortina.

[10]: 148–149 This series of attacks did not obtain the desired objectives, but allowed the Italians to position themselves along a more advanced and more advantageous line that went from Ponte Alto to Rio Felizon, in the locality of Rufiedo.

The Italian command failed to exploit the political advantage of capturing some Bavarian Jägers at Ponte Alto, which unequivocally demonstrated the presence of German troops deployed offensively, despite the fact that Italy was not still at war with Germany.

[12]: 121–122 Advancing up to the Italian lines the Austro-Hungarians were eventually forced to retreat by artillery and rifle fire, returning in the evening to the positions of Piramide Carducci and Forcella dei Castrati.

[12]: 124–125 The Italians decided to wait for the arrival of additional artillery and built up overwhelming numerical superiority and it was not until July 15 that General Ottavio Ragni launched the attack on enemy positions.

For five days there were attacks in three directions, which managed to drive the Austro-Hungarians back off the southern plateau and conquer Forcella dei Castrati, but did not take the strategic northern edge of the mountain.

The winter was particularly hard for the Austro-Hungarians in their precarious position, lacking water or fuel and supplied only by slow columns of porters ascending from Landro along a steep path targeted by Italian artillery.

In August they managed to take the so-called "Fosso degli Alpini", a long depression on the eastern edge of the plateau, delimited by a grassy hill known to the Austro-Hungarians as "Kuppe K".

This position was important because it tied the Austro-Hungarians down on another side of the mountain, and allowed the Italians to protect the ascent route along the Castrati valley, from which they could directly attack enemy lines.

The Austro-Hungarians had one of the best guides in the area, Sepp Innerkofler [de], and, from July, support from the German Alpenkorps who hoisted two mountain guns onto the northern slope of the summit, to strike at a possible Italian advance from the Monte Croce pass.

[10]: 63 In August and September 1915 the Italians mounted a number of probing attacks at the Sentinella Pass, but autumn weather brought fighting to a standstill, with both sides leaving only small garrisons in position.

[10]: 72 With the front lines unchanging after March 1916 the only significant action was from the giant 280mm and 305mm Italian howitzers positioned around the Misurina basin and on the Comelico side of the Monte Croce Pass.

The Italians decided to focus on dislodging the Austrians from various high points around the eastern entrance to the Pass, particularly the rocky outcrop called the Casteletto on the Tofana di Rozes.

[9]: 47 The first action took place on 8 June 1915 when Italian batteries on Monte Padon and Col Toront bombarded the La Corte and Tre Sassi forts as well as Austro-Hungarian infantry positions.

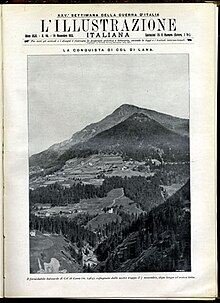

[9]: 48 The Italians launched ten further attacks against Col di Lana and five against the adjoining Mount Sief until General Rossi called a halt on 20 July to await reinforcements.

On April 17, 5020 kilograms of explosives devastated the summit of Col di Lana, killing 110 Austro-Hungarians instantly, while the rest of the garrison was taken prisoner by the I Battalion, 59th Infantry Regiment of the Brigade "Calabria".

Shortly afterwards, after Caporetto, the Italians fell back to the line of the Piave and Monte Grappa, leaving the mountain in Austro-Hungarian hands and thousands of bodies of fallen men.

Apart from some skirmishes between enemy patrols, who had pushed themselves up onto the Marmolada di Punta Penia at 3344m, the sector remained calm until the spring of 1916, when Austro-Hungarian units occupied a number of strongpoints facing the glacier.

[18]: 144 But the Italians, after learning that they were under fire, accelerated the countermining work, and thanks to the help of drilling machines in a short time they managed to reach under the enemy positions, which were blown up in several points, eliminating the danger of artillery attack.

[18]: 150–156 The first action in this sector was a surprise Italian attack on 9 June 1915 by the ""Morbegno battalion" on the Presena glacier at the north end of the Adamello: however they were detected and forced back by sniper fire.

[22] The following spring hostilities resumed on 12 April, when the Alpini at the Giuseppe Garibaldi refuge successfully attacked the Austrian defensive line between Lobbia Alta and Monte Fumo.

Along the Sarca valley, the 4th Division reached Tione and continued towards Trento; Without encountering much resistance, the Pavia brigade pushed its vanguards up to Arco, upstream from Riva del Garda.