Mourning

[11][14] In Ethiopia, an Edir (variants eddir and idir in the Oromo language) is a traditional community organization whose members assist each other during the mourning process.

The traditional period of mourning was nominally 3 years, but usually 25–27 lunar months in practice, and even shorter in the case of necessary officers; the emperor, for example, typically remained in seclusion for just 27 days.

Counting nine days from moment of death, a novena of Masses or other prayers, known as the pasiyám (from the word for "nine"), is performed; the actual funeral and burial may take place within this period or after.

Widows and other women in mourning wore distinctive black caps and veils, generally in a conservative version of any current fashion.

In areas of Russia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Greece, Albania, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain, widows wear black for the rest of their lives.

In 1393, Parisians were treated to the unusual spectacle of a royal funeral carried out in white, for Leo V, King of Armenia, who died in exile.

In the present, no special dress or behavior is obligatory for those in mourning in the general population of the United Kingdom, although ethnic groups and religious faiths have specific rituals, and black is typically worn at funerals.

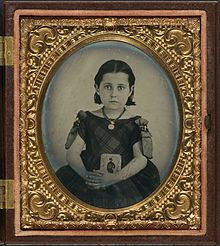

[26] Special caps and bonnets, usually in black or other dark colours, went with these ensembles; mourning jewellery, often made of jet, was also worn, and became highly popular in the Victorian era.

To change one's clothing too early was considered disrespectful to the deceased, and, if the widow was still young and attractive, suggestive of potential sexual promiscuity.

Formal mourning customs culminated during the reign of Queen Victoria (r. 1837–1901), whose long and conspicuous grief over the 1861 death of her husband, Prince Albert, heavily influenced society.

Although clothing fashions began to be more functional and less restrictive in the succeeding Edwardian era (1901-1910), appropriate dress for men and women—including that for the period of mourning—was still strictly prescribed and rigidly adhered to.

[30] The customs were not universally supported, with Charles Voysey writing in 1873 "that it adds needlessly to the gloom and dejection of really afflicted relatives must be apparent to all who have ever taken part in these miserable rites".

[31] The rules gradually relaxed over time, and it became acceptable practice for both sexes to dress in dark colours for up to a year after a death in the family.

[citation needed] In the antebellum South, with social mores that imitated those of England, mourning was just as strictly observed by the upper classes.

In the 19th century, mourning could be quite expensive, as it required a whole new set of clothes and accessories or, at the very least, overdyeing existing garments and taking them out of daily use.

[32][full citation needed] At the end of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dorothy explains to Glinda that she must return home because her aunt and uncle cannot afford to go into mourning for her because it was too expensive.

This is a large vinyl window-cling decal memorializing a deceased loved one, prominently displayed in the rear windows of cars and trucks belonging to close family members and sometimes friends.

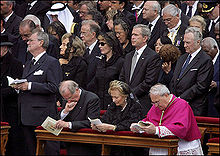

In the case of the death of royalty, the entire country adopts mourning dress and black and purple bunting is displayed from most buildings.

In January 2006, on the death of Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, the emir of Kuwait, a mourning period of 40 days was declared.

In traditional Orthodox communities, the body of the departed would be washed and prepared for burial by family or friends, and then placed in the coffin in the home.

Customs vary among denominations and include temporarily covering or removing statuary, icons and paintings, and use of special liturgical colours, such as violet/purple, during Lent and Holy Week.

Death is not seen as the final "end" in Hinduism, but is seen as a turning point in the seemingly endless journey of the indestructible "atman", or soul, through innumerable bodies of animals and people.

Hence, Hinduism prohibits excessive mourning or lamentation upon death, as this can hinder the passage of the departed soul towards its journey ahead: "As mourners will not help the dead in this world, therefore (the relatives) should not weep, but perform the obsequies to the best of their power.

Hinduism associates death with ritual impurity for the immediate blood family of the deceased, hence during these mourning days, the immediate family must not perform any religious ceremonies (except funerals), must not visit temples or other sacred places, must not serve the sages (holy men), must not give alms, must not read or recite from the sacred scriptures, nor can they attend social functions such as marriages and parties.

The family in mourning are required to bathe twice a day, eat a single simple vegetarian meal, and try to cope with their loss.

This mourning is held in the commemoration of Imam Al Husayn ibn Ali, who was killed along with his 72 companions by Yazid bin Muawiyah.

Mourning is observed in Islam by increased devotion, receiving visitors and condolences, and avoiding decorative clothing and jewelry.

[50] What is prohibited is to express grief by wailing ("bewailing" refers to mourning in a loud voice), shrieking, tearing hair or clothes, breaking things, scratching faces, or uttering phrases that make a Muslim lose faith.

The most known and central stage is Shiva, which is a Jewish mourning practice in which people adjust their behavior as an expression of their bereavement for the week immediately after the burial.

In the West, typically, mirrors are covered and a small tear is made in an item of clothing to indicate a lack of interest in personal vanity.