Multiregional origin of modern humans

The hypothesis contends that the mechanism of clinal variation through a model of "centre and edge" allowed for the necessary balance between genetic drift, gene flow, and selection throughout the Pleistocene, as well as overall evolution as a global species, but while retaining regional differences in certain morphological features.

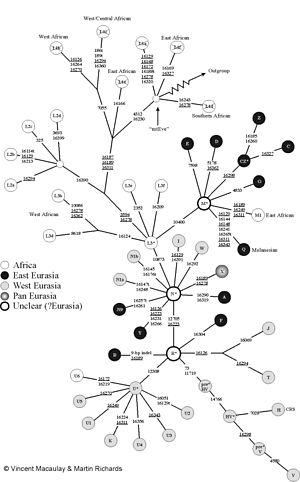

"The African replacement model has gained the widest acceptance owing mainly to genetic data (particularly mitochondrial DNA) from existing populations.

[10][11][1] Wolpoff credits Franz Weidenreich's "Polycentric" hypothesis of human origins as a major influence, but cautions that this should not be confused with polygenism, or Carleton Coon's model that minimized gene flow.

Alan Templeton for example notes that this confusion has led to the error that gene flow between different populations was added to the Multiregional hypothesis as a "special pleading in response to recent difficulties", despite the fact: "parallel evolution was never part of the multiregional model, much less its core, whereas gene flow was not a recent addition, but rather was present in the model from the very beginning"[15] (emphasis in original).

[21] However, James Leibold, a political historian of modern China, has argued the support for Wu's model is largely rooted in Chinese nationalism.

[23] Chris Stringer, a leading proponent of the more mainstream recent African origin theory, debated Multiregionalists such as Wolpoff and Thorne in a series of publications throughout the late 1980s and 1990s.

[24][25][26][27] Stringer describes how he considers the original Multiregional hypothesis to have been modified over time into a weaker variant that now allows a much greater role for Africa in human evolution, including anatomical modernity (and subsequently less regional continuity than was first proposed).

But in 2002, Alan Templeton published a genetic analysis involving other loci in the genome as well, and this showed that some variants that are present in modern populations existed already in Asia hundreds of thousands of years ago.

For example, in 2001 Wolpoff and colleagues published an analysis of character traits of the skulls of early modern human fossils in Australia and central Europe.

They concluded that the diversity of these recent humans could not "result exclusively from a single late Pleistocene dispersal", and implied dual ancestry for each region, involving interbreeding with Africans.

He found that: "a plurality (eight) of the seventeen non-metric features link Sangiran to modern Australians" and that these "are suggestive of morphological continuity, which implies the presence of a genetic continuum in Australasia dating back at least one million years"[41] but Colin Groves has criticized Kramer's methodology, pointing out that the polarity of characters was not tested and that the study is actually inconclusive.

Many are also commonly found on the crania and mandibles of anatomically-modern Homo sapiens from other geographical locations, being especially prevalent on the robust Mesolithic skeletal material from North Africa.

Durband (2007) in contrast states that "features cited as showing continuity between Sangiran 17 and the Kow Swamp sample disappeared in the new, more orthognathic reconstruction of that fossil that was recently completed".

[45] Baba et al. who newly restored the face of Sangiran 17 concluded: "regional continuity in Australasia is far less evident than Thorne and Wolpoff argued".

[47][48] The sequence is said to start with Lantian and Peking Man, traced to Dali, to Late Pleistocene specimens (e.g. Liujiang) and recent Chinese.

However, according to Chris Stringer, Habgood's study suffered from not including enough fossil samples from North Africa, many of which exhibit the small combination he considered to be region-specific to China.

[51][52] Stringer (1992) however found that shovel-shaped incisors are present on >70% of the early Holocene Wadi Halfa fossil sample from North Africa, and common elsewhere.

[54][55][56] The sequence starts with the earliest dated Neanderthal specimens (Krapina and Saccopastore skulls) traced through the mid-Late Pleistocene (e.g. La Ferrassie 1) to Vindija Cave, and late Upper Palaeolithic Cro-Magnons or recent Europeans.

"[33]Frayer et al. (1993) consider there to be at least four features in combination that are unique to the European fossil record: a horizontal-oval shaped mandibular foramen, anterior mastoid tubercle, suprainiac fossa, and narrowing of the nasal breadth associated with tooth-size reduction.

[61] More recent claims regarding continuity in skeletal morphology in Europe focus on fossils with both Neanderthal and modern anatomical traits, to provide evidence of interbreeding rather than replacement.

In addition, the Y chromosome data indicated a later expansion back into Africa from Asia, demonstrating that gene flow between regions was not unidirectional.

[95][96] For example, analyses of a region of RRM2P4 (ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit pseudogene 4) showed a coalescence time of about 2 Mya, with a clear root in Asia,[97][98] while the MAPT locus at 17q21.31 is split into two deep genetic lineages, one of which is common in and largely confined to the present European population, suggesting inheritance from Neanderthals.

[110] In a 2005 review and analysis of the genetic lineages of 25 chromosomal regions, Alan Templeton found evidence of more than 34 occurrences of gene flow between Africa and Eurasia.