Murphy's law

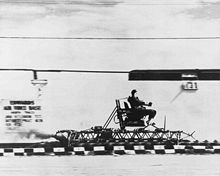

Though similar statements and concepts have been made over the course of history, the law itself was coined by, and named after, American aerospace engineer Edward A. Murphy Jr.; its exact origins are debated, but it is generally agreed it originated from Murphy and his team following a mishap during rocket sled tests some time between 1948 and 1949, and was finalized and first popularized by testing project head John Stapp during a later press conference.

The perceived perversity of the universe has long been a subject of comment, and precursors to the modern version of Murphy's law are abundant.

As quoted by Richard Rhodes,[4]: 187 Matthews said, "The familiar version of Murphy's law is not quite 50 years old, but the essential idea behind it has been around for centuries.

[…] The modern version of Murphy's Law has its roots in U.S. Air Force studies performed in 1949 on the effects of rapid deceleration on pilots."

[6] ADS member Stephen Goranson found a version of the law, not yet generalized or bearing that name, in a report by Alfred Holt at an 1877 meeting of an engineering society.

Whether we must attribute this to the malignity of matter or to the total depravity of inanimate things, whether the exciting cause is hurry, worry, or what not, the fact remains.

The law's name supposedly stems from an attempt to use new measurement devices developed by Edward A. Murphy, a United States Air Force (USAF) captain and aeronautical engineer.

[15] The phrase was coined in an adverse reaction to something Murphy said when his devices failed to perform and was eventually cast into its present form prior to a press conference some months later – the first ever (of many) given by John Stapp, a USAF colonel and flight surgeon in the 1950s.

Edward Murphy proposed using electronic strain gauges attached to the restraining clamps of Stapp's harness to measure the force exerted on them by his rapid deceleration.

During a trial run of this method using a chimpanzee, supposedly around June 1949, Murphy's assistant wired the harness and the rocket sled was launched.

George E. Nichols, an engineer and quality assurance manager with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was present at the time, recalled in an interview that Murphy blamed the failure on his assistant after the failed test, saying, "If that guy has any way of making a mistake, he will.

The phrase first received public attention during a press conference in which Stapp was asked how it was that nobody had been severely injured during the rocket sled tests.

Nichols believes Murphy was unwilling to take the responsibility for the device's initial failure (by itself a blip of no large significance) and is to be doubly damned for not allowing the MX981 team time to validate the sensor's operability and for trying to blame an underling in the embarrassing aftermath.

The next citations are not found until 1955, when the May–June issue of Aviation Mechanics Bulletin included the line "Murphy's law: If an aircraft part can be installed incorrectly, someone will install it that way",[21] and Lloyd Mallan's book Men, Rockets and Space Rats, referred to: "Colonel Stapp's favorite takeoff on sober scientific laws—Murphy's law, Stapp calls it—'Everything that can possibly go wrong will go wrong'."

"[23] ADS member Stephen Goranson, investigating this in 2008 and 2009, found that Anne Roe's papers, held in the American Philosophical Society's archives in Philadelphia, identified the interviewed physicist as Howard Percy "Bob" Robertson (1903–1961).

John Paul Stapp, Edward A. Murphy, Jr., and George Nichols were jointly awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2003 in engineering " for (probably) giving birth to the name".

Examples of these "Murphy's laws" include those for military tactics, technology, romance, social relations, research, and business.