Muscle contraction

[1] In natural movements that underlie locomotor activity, muscle contractions are multifaceted as they are able to produce changes in length and tension in a time-varying manner.

[1][7] In natural movements that underlie locomotor activity, muscle contractions are multifaceted as they are able to produce changes in length and tension in a time-varying manner.

A concentric contraction of the triceps would change the angle of the joint in the opposite direction, straightening the arm and moving the hand towards the leg.

[11] During an eccentric contraction of the biceps muscle, the elbow starts the movement while bent and then straightens as the hand moves away from the shoulder.

During an eccentric contraction of the triceps muscle, the elbow starts the movement straight and then bends as the hand moves towards the shoulder.

During a concentric contraction, contractile muscle myofilaments of myosin and actin slide past each other, pulling the Z-lines together.

Exercise featuring a heavy eccentric load can actually support a greater weight (muscles are approximately 40% stronger during eccentric contractions than during concentric contractions) and also results in greater muscular damage and delayed onset muscle soreness one to two days after training.

[10][12] While unaccustomed heavy eccentric contractions can easily lead to overtraining, moderate training may confer protection against injury.

Smooth muscle forms blood vessels, the gastrointestinal tract, and other areas in the body that produce sustained contractions.

The brain sends electrochemical signals through the nervous system to the motor neuron that innervates several muscle fibers.

[16] In the case of some reflexes, the signal to contract can originate in the spinal cord through a feedback loop with the grey matter.

As a result, the sarcolemma reverses polarity and its voltage quickly jumps from the resting membrane potential of -90mV to as high as +75mV as sodium enters.

Excitation–contraction coupling (ECC) is the process by which a muscular action potential in the muscle fiber causes myofibrils to contract.

The close apposition of a transverse tubule and two SR regions containing RyRs is described as a triad and is predominantly where excitation–contraction coupling takes place.

As ryanodine receptors open, Ca2+ is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the local junctional space and diffuses into the bulk cytoplasm to cause a calcium spark.

This fine myofilament maintains uniform tension across the sarcomere by pulling the thick filament into a central position.

When Ca2+ is no longer present on the thin filament, the tropomyosin changes conformation back to its previous state so as to block the binding sites again.

In multiple fiber summation, if the central nervous system sends a weak signal to contract a muscle, the smaller motor units, being more excitable than the larger ones, are stimulated first.

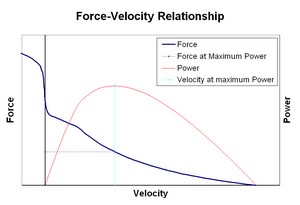

When stretched or shortened beyond this (whether due to the action of the muscle itself or by an outside force), the maximum active tension generated decreases.

The motor system can thus actively control joint damping via the simultaneous contraction (co-contraction) of opposing muscle groups.

Multiunit smooth muscle cells contract by being separately stimulated by nerves of the autonomic nervous system.

The two sources for cytosolic Ca2+ in smooth muscle cells are the extracellular Ca2+ entering through calcium channels and the Ca2+ ions that are released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

During contraction of muscle, rapidly cycling crossbridges form between activated actin and phosphorylated myosin, generating force.

Conversely, postganglionic nerve fibers of the sympathetic nervous system release the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, which bind to adrenergic receptors that are also metabotropic.

In both skeletal and cardiac muscle excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling, depolarization conduction and Ca2+ release processes occur.

At high heart rates, phospholamban is phosphorylated and deactivated thus taking most Ca2+ from the cytoplasm back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

In annelids such as earthworms and leeches, circular and longitudinal muscles cells form the body wall of these animals and are responsible for their movement.

[44][45] These alternating waves of circular and longitudinal contractions is called peristalsis, which underlies the creeping movement of earthworms.

In 1952, the term excitation–contraction coupling was coined to describe the physiological process of converting an electrical stimulus to a mechanical response.

[50] This process is fundamental to muscle physiology, whereby the electrical stimulus is usually an action potential and the mechanical response is contraction.