Music for the Requiem Mass

This church service has inspired hundreds of compositions, including settings by Victoria, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi, Fauré, Dvořák, Duruflé and Britten.

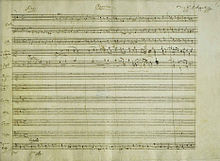

By Mozart's time (1791) it was standard to embed the dramatic and long Day of Wrath sequence, and to score with orchestra.

Eventually many settings of the Requiem, not least Verdi's (1874), were essentially concert pieces unsuitable for church service.

In Paradisum was traditionally said or sung as the body left the church, and the Libera Me is said/sung at the burial site before interment.

These became included in musical settings of the Requiem in the 19th century as composers began to treat the form more liberally.

The sequence employed in the Requiem, Dies irae, attributed to Thomas of Celano (c. 1200 – c. 1260–1270), has been called "the greatest of hymns", worthy of "supreme admiration".

Domine Iesu Christe, Rex gloriæ, libera animas omnium fidelium defunctorum de pœnis inferni et de profundo lacu: libera eas de ore leonis, ne absorbeat eas tartarus, ne cadant in obscurum: sed signifer sanctus Michael repræsentet eas in lucem sanctam: Quam olim Abrahæ promisisti, et semini eius.

Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, deliver the souls of all the faithful departed from the pains of hell and from the bottomless pit: deliver them from the lion's mouth, that Tartarus swallow them not up, that they fall not into darkness, but let the standard-bearer holy Michael lead them into that holy light: Which Thou didst promise of old to Abraham and to his seed.

We offer to Thee, O Lord, sacrifices and prayers: do Thou receive them in behalf of those souls of whom we make memorial this day.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: dona eis requiem sempiternam.

Lux æterna luceat eis, Domine: Cum Sanctis tuis in æternum: quia pius es.

Eternal rest give to them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them: With Thy Saints for evermore, for Thou art gracious.

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna, in die illa tremenda: Quando cæli movendi sunt et terra: Dum veneris iudicare sæculum per ignem.

Tremens factus sum ego, et timeo, dum discussio venerit, atque ventura ira.

Chorus Angelorum te suscipiat, et cum Lazaro quondam paupere æternam habeas requiem.

The Requiem by Johannes Ockeghem, written sometime in the later half of the 15th century, is the earliest surviving polyphonic setting.

There was a setting by the elder composer Guillaume Du Fay, possibly earlier, which is now lost: Ockeghem's may have been modelled on it.

Fauré omits the Dies iræ, while the very same text had often been set by French composers in previous centuries as a stand-alone work.

The Introit and Kyrie, being immediately adjacent in the actual Roman Catholic liturgy, are often composed as one movement.

Beginning in the 18th century and continuing through the 19th, many composers wrote what are effectively concert works, which by virtue of employing forces too large, or lasting such a considerable duration, prevent them being readily used in an ordinary funeral service; the requiems of Gossec, Berlioz, Verdi, and Dvořák are essentially dramatic concert oratorios.

A counter-reaction to this tendency came from the Cecilian movement, which recommended restrained accompaniment for liturgical music, and frowned upon the use of operatic vocal soloists.

These often include extra-liturgical poems of a pacifist or non-liturgical nature; for example, the War Requiem of Benjamin Britten juxtaposes the Latin text with the poetry of Wilfred Owen, Krzysztof Penderecki's Polish Requiem includes a traditional Polish hymn within the sequence, and Robert Steadman's Mass in Black intersperses environmental poetry and prophecies of Nostradamus.

Recent requiem works by Taiwanese composers Tyzen Hsiao and Fan-Long Ko follow in this tradition, honouring victims of the February 28 Incident and subsequent White Terror.

Igor Stravinsky's Requiem Canticles mixes instrumental movements with segments of the "Introit," "Dies irae," "Pie Jesu," and "Libera me."