Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was dominated by a warrior elite society and consisted of a network of palace-centered states that developed rigid hierarchical, political, social, and economic systems.

This land is geographically defined in an inscription from the reign of Amenhotep III (r. c. 1390–1352 BC), where a number of Danaya cities are mentioned, which cover the largest part of southern mainland Greece.

[2] Historian Bernard Sergent notes that archaeology alone is not able to solve the issue and that the majority of Hellenists believed Mycenaeans spoke a non-Indo-European Minoan language before Linear B was deciphered in 1952.

[29] Notwithstanding the above academic disputes, the mainstream consensus among modern Mycenologists is that Mycenaean civilization began around 1750 BC,[1] earlier than the Shaft Graves,[30] originating and evolving from the local socio-cultural landscape of the Early and Middle Bronze Age in mainland Greece with influences from Minoan Crete.

[33] A number of centers of power emerged in southern mainland Greece dominated by a warrior elite society;[3][31] while the typical dwellings of that era were an early type of megaron buildings, some more complex structures are classified as forerunners of the later palaces.

[38] In the early 15th century BC, commerce intensified with Mycenaean pottery reaching the western coast of Asia Minor, including Miletus and Troy, Cyprus, Lebanon, Palestine and Egypt.

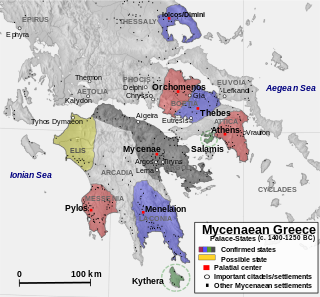

[3] Additional palaces were built in Midea and Pylos in Peloponnese, Athens, Eleusis, Thebes and Orchomenos in Central Greece and Iolcos, in Thessaly, the latter being the northernmost Mycenaean center.

[54] Moreover, Ahhiyawa achieved considerable political influence in parts of Western Anatolia, typically by encouraging anti-Hittite uprisings and collaborating with local vassal rulers.

[76] The site of Mycenae experienced a gradual loss of political and economic status, while Tiryns, also in the Argolid region, expanded its settlement and became the largest local center during the post-palatial period, in Late Helladic IIIC, c. 1200–1050 BC.

[83] Mycenaean palatial states, or centrally organized palace-operating polities, are recorded in ancient Greek literature and mythology (e.g., Iliad, Catalogue of Ships) and confirmed by discoveries made by modern archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann.

The preserved Linear B records in Pylos and Knossos indicate that the palaces were closely monitoring a variety of industries and commodities, the organization of land management and the rations given to the dependent personnel.

[99] The archives of Pylos display a specialized workforce, where each worker belonged to a precise category and was assigned to a specific task in the stages of production, notably in textiles.

[104] The Mycenaean economy also featured large-scale manufacturing as testified by the extent of workshop complexes that have been discovered, the largest known to date being the recent ceramic and hydraulic installations found in Euonymeia, next to Athens, that produced tableware, textiles, sails, and ropes for export and shipbuilding.

[107] Based on archaeological findings in the Middle East, in particular physical artifacts, textual references, inscriptions and wall paintings, it appears that Mycenaean Greeks achieved strong commercial and cultural interaction with most of the Bronze Age people living in this region: Canaanites, Kassites, Mitanni, Assyrians, and Egyptians.

The throne was generally found on the right-hand side upon entering the room, while the interior of the megaron was lavishly decorated, flaunting images designed intentionally to demonstrate the political and religious power of the ruler.

The principal Mycenaean centers were well-fortified and usually situated on an elevated terrain, like on the Acropolis of Athens, Tiryns and Mycenae or on coastal plains, in the case of Gla.

[162] Cyclopean is the term normally applied to the masonry characteristics of Mycenaean fortification systems and describes walls built of large, unworked boulders more than 8 m (26 ft) thick and weighing several metric tonnes.

The observed uniformity in domestic architecture came probably as a result of a shared past among the communities of the Greek mainland rather than as a consequence of cultural expansion of the Mycenaean Koine.

[174] Later in the 13th century BC, Mycenaean warfare underwent major changes both in tactics and weaponry and armed units became more uniform and flexible, while weapons became smaller and lighter.

This is less true of pottery, although the (very untypical) Mycenaean palace amphora with octopus (NAMA 6725) clearly derives directly from the Minoan "Marine Style", and it ceases to be the case after about 1350 BC.

Mycenaean drinking vessels such as the stemmed cups contained single decorative motifs such as a shell, an octopus or a flower painted on the side facing away from the drinker.

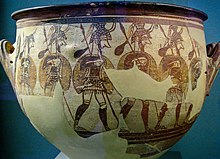

[188] The Mycenaean Greeks also painted entire scenes (called "Pictorial Style") on their vessels depicting warriors, chariots, horses and deities reminiscent of events described in Homer's Iliad.

The statuary of the period consists for the most part of small terracotta figurines found at almost every Mycenaean site in mainland Greece—in tombs, in settlement debris, and occasionally in cult contexts (Tiryns, Agios Konstantinos on Methana).

[202] It has been argued that this form dates back to the Kurgan culture;[203] however, Mycenaean burials are in actuality an indigenous development of mainland Greece with the Shaft Graves housing native rulers.

[216] In the 8th century BC, after the end of the so-called Greek Dark Ages, Greece emerged with a network of myths and legends, the greatest of all being that of the Trojan Epic Cycle.

[222] The Mycenaean Greeks were also pioneers in the field of engineering, launching large-scale projects unmatched in Europe until the Roman period, such as fortifications, bridges, culverts, aqueducts, dams and roads suitable for wheeled traffic.

This is corroborated by sequenced genomes of Middle Bronze Age individuals from northern Greece, who had a much higher proportion of steppe-related ancestry; the timing of this gene flow was estimated at 2,300 BCE, and is consistent with the dominant linguistic theories explaining the emergence of the Proto-Greek language.

[238] In a comment on the study by Lazaridis et al. (2022), Paul Heggarty of the Max Planck Institute expressed doubts regarding the connection between the "small contribution in Mycenaean Greece" of the "ancestral mix of Yamnaya culture" and the steppe as the "earliest, original source" of Indo-European languages.

[239] A study by Skourtanioti et al. (2023) generated genome-wide data from 95 Bronze Age individuals from mainland Greece and the Aegean, which was analysed in the context of all previously published samples from the region.

[241] This influx of steppe-related ancestry was related to Mycenaean domination of the island from the 15th century BC onwards, and was possibly also due in part to later migrations from more distant areas such as Italy.