Mysticism

Derived from the Greek word μύω múō, meaning "to close" or "to conceal", mysticism came to refer to the biblical, liturgical (and sacramental), spiritual, and contemplative dimensions of early and medieval Christianity.

[2] During the early modern period, the definition of mysticism grew to include a broad range of beliefs and ideologies related to "extraordinary experiences and states of mind".

A passage of Cretans by Euripides seems to explain that the μύστης (initiate) who devotes himself to an ascetic life, renounces sexual activities, and avoids contact with the dead becomes known as βάκχος.

[10] Parsons warns that "what might at times seem to be a straightforward phenomenon exhibiting an unambiguous commonality has become, at least within the academic study of religion, opaque and controversial on multiple levels".

Dan Merkur also notes that union with God or the Absolute is a too limited definition, since there are also traditions which aim not at a sense of unity, but of nothingness, such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Meister Eckhart.

[web 4][note 6] Parsons stresses the importance of distinguishing between temporary experiences and mysticism as a process, which is embodied within a "religious matrix" of texts and practices.

[33] Comparable Asian terms are bodhi, kenshō, and satori in Buddhism, commonly translated as "enlightenment", and vipassana, which all point to cognitive processes of intuition and comprehension.

This kind of mysticism was a general category that included the positive knowledge of God obtained, for example, through practical "repentant activity" (e.g., as part of sacramental participation), rather being about passive esoteric/transcendent religious ecstasy: it was an antidote the "self-aggrandizing hyper-inquisitiveness" of Scholasticism and was attainable even by simple and uneducated people.

By the middle of the 17th century, "the mystical" is increasingly applied exclusively to the religious realm, separating religion and "natural philosophy" as two distinct approaches to the discovery of the hidden meaning of the universe.

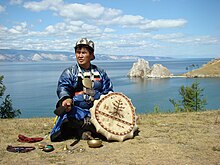

[64] A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into trance during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.

[66][67] The Eleusinian Mysteries, (Greek: Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια) were annual initiation ceremonies in the cults of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, held in secret at Eleusis (near Athens) in ancient Greece.

The Eastern Orthodox Church has a long tradition of theoria (intimate experience) and hesychia (inner stillness), in which contemplative prayer silences the mind to progress along the path of theosis (deification).

Theosis, practical unity with and conformity to God, is obtained by engaging in contemplative prayer, the first stage of theoria,[71][note 16] which results from the cultivation of watchfulness (nepsis).

[note 17][71] It is the main aim of hesychasm, which was developed in the thought St. Symeon the New Theologian, embraced by the monastic communities on Mount Athos, and most notably defended by St. Gregory Palamas against the Greek humanist philosopher Barlaam of Calabria.

The Late Middle Ages saw the clash between the Dominican and Franciscan schools of thought, which was also a conflict between two different mystical theologies: on the one hand that of Dominic de Guzmán and on the other that of Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, Bonaventure, and Angela of Foligno.

Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between an unchanging, eternal and mysterious Ein Sof (no end) and the mortal and finite universe (his creation).

These teachings are thus held by followers in Judaism to define the inner meaning of both the Hebrew Bible and traditional Rabbinic literature, their formerly concealed transmitted dimension, as well as to explain the significance of Jewish religious observances.

20th-century interest in Kabbalah has inspired cross-denominational Jewish renewal and contributed to wider non-Jewish contemporary spirituality, as well as engaging its flourishing emergence and historical re-emphasis through newly established academic investigation.

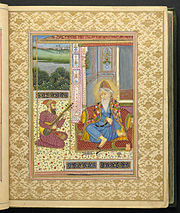

Some sufic beliefs and practices have been found unorthodox by other Muslims; for instance Mansur al-Hallaj was put to death for blasphemy after uttering the phrase Ana'l Haqq, "I am the Truth" (i.e. God) in a trance.

Notable classical Sufis include Jalaluddin Rumi, Fariduddin Attar, Sultan Bahoo, Sayyed Sadique Ali Husaini, Saadi Shirazi, and Hafez, all major poets in the Persian language.

An interest in Sufism revived in non-Muslim countries during the modern era, led by such figures as Inayat Khan and Idries Shah (both in the UK), Rene Guenon (France), and Ivan Aguéli (Sweden).

[84] In Hinduism, various sadhanas (spiritual disciplines) aim at overcoming ignorance (avidya) and transcending one's identification with body, mind, and ego to attain moksha, liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

[citation needed] There is no concentration on the breath (as in other Dharmic religions), but chiefly, the practice of simran consists of the remembrance of God through the recitation of the Divine Name.

[107] Buddhism originated in India, sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, but is now mostly practiced in other countries, where it developed into a number of traditions, the main ones being Therevada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

[110] It is best known in the west from the Vipassana movement, a number of branches of modern Theravāda Buddhism from Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Sri Lanka, and includes contemporary American Buddhist teachers such as Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield.

[note 21] Vijñapti-mātra, coupled with Buddha-nature or tathagatagarba, has been an influential concept in the subsequent development of Mahayana Buddhism, not only in India, but also in China and Tibet, most notable in the Chán (Zen) and Dzogchen traditions.

[133] The monistic type, which according to Zaehner is based upon an experience of the unity of one's soul,[133][note 23] includes Buddhism and Hindu schools such as Samkhya and Advaita vedanta.

"[7]Yet, Gellman notes that so-called mystical experience is not a transitional event, as William James claimed, but an "abiding consciousness, accompanying a person throughout the day, or parts of it.

The term "mystical experience" evolved as a distinctive concept since the 19th century, laying sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior.

Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.