Irish mythology

The Mythological Cycle consists of tales and poems about the god-like Tuatha Dé Danann, who are based on Ireland's pagan deities, and other mythical races like the Fomorians.

The Ulster Cycle consists of heroic legends relating to the Ulaid, the most important of which is the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("Cattle Raid of Cooley").

[2] The Fenian Cycle focuses on the exploits of the mythical hero Finn and his warrior band the Fianna, including the lengthy Acallam na Senórach ("Tales of the Elders").

[2] There are also mythological texts that do not fit into any of the cycles; these include the echtrai tales of journeys to the Otherworld (such as The Voyage of Bran), and the Dindsenchas ("lore of places").

They are also said to control the fertility of the land; the tale De Gabáil in t-Sída says the first Gaels had to establish friendship with the Tuath Dé before they could raise crops and herds.

Many are associated with specific places in the landscape, especially the sídhe: prominent ancient burial mounds such as Brú na Bóinne, which are entrances to Otherworld realms.

[3] Several of the Tuath Dé are cognate with ancient Celtic deities: Lugh with Lugus, Brigid with Brigantia, Nuada with Nodons, and Ogma with Ogmios.

[3] Many of the Tuath Dé are not defined by singular qualities, but are more of the nature of well-rounded humans, who have areas of special interests or skills like the druidic arts they learned before traveling to Ireland.

[7] Irish goddesses or Otherworldly women are usually connected to the land, the waters, and sovereignty, and are often seen as the oldest ancestors of the people in the region or nation.

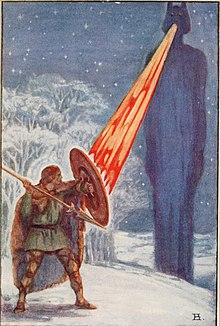

Badb Catha, for instance, is "the Raven of Battle",[13] and in the Táin Bó Cúailnge, The Morrígan shapeshifts into an eel, a wolf, and a cow.

[20] Other 15th-century manuscripts, such as The Book of Fermoy, also contain interesting materials, as do such later syncretic works such as Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (The History of Ireland) (c. 1640).

Most of these manuscripts were created by Christian monks, who may well have been torn between a desire to record their native culture and hostility to pagan beliefs, resulting in some of the gods being euhemerised.

Many of the later sources may also have formed parts of a propaganda effort designed to create a history for the people of Ireland that could bear comparison with the mythological descent of their British invaders from the founders of Rome, as promulgated by Geoffrey of Monmouth and others.

The revisionists point to passages apparently influenced by the Iliad in Táin Bó Cuailnge, and to the Togail Troí, an Irish adaptation of Dares Phrygius' De excidio Troiae historia, found in the Book of Leinster.

The people include Cessair and her followers, the Formorians, the Partholinians, the Nemedians, the Firbolgs, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the Milesians.

The Metrical Dindshenchas is the great onomastics work of early Ireland, giving the naming legends of significant places in a sequence of poems.

Texts such as Lebor Gabála Érenn and Cath Maige Tuireadh present them as kings and heroes of the distant past, complete with death-tales.

Even after they are displaced as the rulers of Ireland, characters such as Lugh, the Mórrígan, Aengus and Manannán Mac Lir appear in stories set centuries later, betraying their immortality.

Nuada is cognate with the British god Nodens; Lugh is a reflex of the pan-Celtic deity Lugus, the name of whom may indicate "Light"; Tuireann may be related to the Gaulish Taranis; Ogma to Ogmios; the Badb to Catubodua.

It consists of a group of heroic tales dealing with the lives of Conchobar mac Nessa, king of Ulster, the great hero Cú Chulainn, who was the son of Lug (Lugh), and of their friends, lovers, and enemies.

These are the Ulaid, or people of the North-Eastern corner of Ireland and the action of the stories centres round the royal court at Emain Macha (known in English as Navan Fort), close to the modern town of Armagh.

The cycle consists of stories of the births, early lives and training, wooing, battles, feastings, and deaths of the heroes.

Other important Ulster Cycle tales include The Tragic Death of Aife's only Son, Bricriu's Feast, and The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel.

The Exile of the Sons of Usnach, better known as the tragedy of Deirdre and the source of plays by John Millington Synge, William Butler Yeats, and Vincent Woods, is also part of this cycle.

The text records conversations between Caílte mac Rónáin and Oisín, the last surviving members of the Fianna, and Saint Patrick, and consists of about 8,000 lines.

Two of the greatest of the Irish tales, Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne) and Oisín in Tír na nÓg form part of the cycle.

[20] It was part of the duty of the medieval Irish bards, or court poets, to record the history of the family and the genealogy of the king they served.

However, the greatest glory of the Kings' Cycle is the Buile Shuibhne (The Frenzy of Sweeney), a 12th century tale told in verse and prose.

Suibhne, king of Dál nAraidi, was cursed by St. Ronan and became a kind of half-man, half bird, condemned to live out his life in the woods, fleeing from his human companions.

The adventures, or echtrae, are a group of stories of visits to the Irish Other World (which may be westward across the sea, underground, or simply invisible to mortals).