Naive set theory

Naive set theory suffices for many purposes, while also serving as a stepping stone towards more formal treatments.

It was created at the end of the 19th century by Georg Cantor as part of his study of infinite sets[5] and developed by Gottlob Frege in his Grundgesetze der Arithmetik.

It may refer to The assumption that any property may be used to form a set, without restriction, leads to paradoxes.

Some believe that Georg Cantor's set theory was not actually implicated in the set-theoretic paradoxes (see Frápolli 1991).

One difficulty in determining this with certainty is that Cantor did not provide an axiomatization of his system.

It is "naive" in that the language and notations are those of ordinary informal mathematics, and in that it does not deal with consistency or completeness of the axiom system.

It follows from Gödel's incompleteness theorems that a sufficiently complicated first order logic system (which includes most common axiomatic set theories) cannot be proved consistent from within the theory itself – even if it actually is consistent.

In everyday mathematics the best choice may be informal use of axiomatic set theory.

Likewise, formal proofs occur only when warranted by exceptional circumstances.

It is considerably easier to read and write (in the formulation of most statements, proofs, and lines of discussion) and is less error-prone than a strictly formal approach.

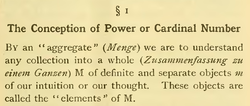

He wrote in his 1915 article Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre: Unter einer 'Menge' verstehen wir jede Zusammenfassung M von bestimmten wohlunterschiedenen Objekten unserer Anschauung oder unseres Denkens (welche die 'Elemente' von M genannt werden) zu einem Ganzen.A set is a gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception or of our thought—which are called elements of the set.It does not follow from this definition how sets can be formed, and what operations on sets again will produce a set.

The problem, in this context, with informally formulated set theories, not derived from (and implying) any particular axiomatic theory, is that there may be several widely differing formalized versions, that have both different sets and different rules for how new sets may be formed, that all conform to the original informal definition.

For example, Cantor's verbatim definition allows for considerable freedom in what constitutes a set.

The purpose is to keep the often deep and difficult issues of consistency away from the, usually simpler, context at hand.

An explicit ruling out of all conceivable inconsistencies (paradoxes) cannot be achieved for an axiomatic set theory anyway, due to Gödel's second incompleteness theorem, so this does not at all hamper the utility of naive set theory as compared to axiomatic set theory in the simple contexts considered below.

Note the following points: (These are consequences of the definition of equality in the previous section.)

Usually when trying to prove that two sets are equal, one aims to show these two inclusions.

For instance, when investigating properties of the real numbers R (and subsets of R), R may be taken as the universal set.

It is written as A \ B or A − B. Symbolically, these are respectively The set B doesn't have to be a subset of A for A \ B to make sense; this is the difference between the relative complement and the absolute complement (AC = U \ A) from the previous section.

(The notation (a, b) is also used to denote an open interval on the real number line, but the context should make it clear which meaning is intended.

Otherwise, the notation ]a, b[ may be used to denote the open interval whereas (a, b) is used for the ordered pair).

This definition may be extended to a set A × B × C of ordered triples, and more generally to sets of ordered n-tuples for any positive integer n. It is even possible to define infinite Cartesian products, but this requires a more recondite definition of the product.

Cartesian products were first developed by René Descartes in the context of analytic geometry.

[14] Related to the above constructions is formation of the set where the statement following the implication certainly is false.

It follows, from the definition of Y, using the usual inference rules (and some afterthought when reading the proof in the linked article below) both that Y ∈ Y → {} ≠ {} and Y ∈ Y holds, hence {} ≠ {}.

With the axiom schema of specification instead of unrestricted comprehension, the conclusion Y ∈ Y does not hold and hence {} ≠ {} is not a logical consequence.

Nonetheless, the possibility of x ∈ x is often removed explicitly[16] or, e.g. in ZFC, implicitly,[17] by demanding the axiom of regularity to hold.

[18] The axiom schema of separation is simply too weak (while unrestricted comprehension is a very strong axiom—too strong for set theory) to develop set theory with its usual operations and constructions outlined above.

Not all conceivable axioms can be combined freely into consistent theories.

For example, the axiom of choice of ZFC is incompatible with the conceivable "every set of reals is Lebesgue measurable".