National Treasure (Japan)

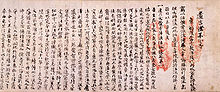

The other 80% are paintings; scrolls; sutras; works of calligraphy; sculptures of wood, bronze, lacquer or stone; crafts such as pottery and lacquerware carvings; metalworks; swords and textiles; and archaeological and historical artifacts.

The designation of the Akasaka Palace in 2009, the Tomioka Silk Mill in 2014 and of the Kaichi School added three modern, post-Meiji Restoration, National Treasures.

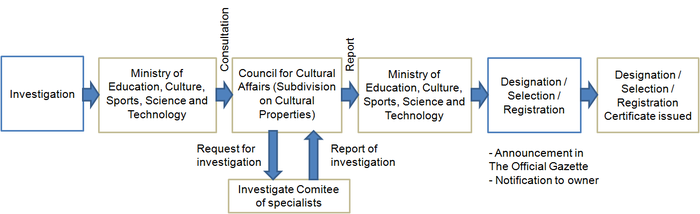

[2] Methods of protecting designated National Treasures include restrictions on alterations, transfer, and export, as well as financial support in the form of grants and tax reduction.

[7][8][9] In 1871, the Daijō-kan issued a decree to protect Japanese antiquities called the Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts (古器旧物保存方, koki kyūbutsu hozonkata).

[9] A survey conducted in association with Okakura Kakuzō and Ernest Fenollosa between 1888 and 1897 was designed to evaluate and catalogue 210,000 objects of artistic or historic merit.

[4][8] The end of the 19th century was a period of political change in Japan as cultural values moved from the enthusiastic adoption of western ideas to a newly discovered interest in Japanese heritage.

[4][9] Formulated under the guidance of architectural historian and architect Itō Chūta, the law established (in 20 articles) government funding for the preservation of buildings and the restoration of artworks.

A second law was passed on December 15, 1897, that provided supplementary provisions to designate works of art in the possession of temples or shrines as "National Treasures" (国宝, kokuhō).

The new law also provided for pieces of religious architecture to be designated as a "Specially Protected Building" (特別保護建造物, tokubetsu hogo kenzōbutsu).

Owners were required to register designated objects with newly created museums, which were granted first option of purchase in case of sale.

Eventually these efforts resulted in the 1919 Historical Sites, Places of Scenic Beauty, and Natural Monuments Preservation Law (史蹟名勝天然紀念物保存法, shiseki meishō enrenkinenbutsu hozonhō), protecting and cataloguing such properties in the same manner as temples, shrines, and pieces of art.

[4] By 1939, nine categories of properties consisting of 8,282 items (paintings, sculptures, architecture, documents, books, calligraphy, swords, crafts, and archaeological resources) had been designated as National Treasures and were forbidden to be exported.

[16] When the kon-dō of Hōryū-ji, one of the oldest extant wooden buildings in the world and the first to be protected under the "Ancient Temples and Shrines Preservation Law", caught fire on January 26, 1949, valuable seventh-century wall paintings were damaged.

[23] The techniques to be protected included the mounting of paintings and calligraphy on scrolls; the repair of lacquerware and wooden sculptures; and the production of Noh masks, costumes, and instruments.

[19] As a result of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, 714[nb 2] cultural properties including five National Treasure buildings suffered damage.

[nb 6][25] Cultural products with a tangible form that possess high historic, artistic, and academic value for Japan are listed in a three-tier system.

The agency generally distinguishes between "buildings and structures" (建造物, kenzōbutsu) and "fine arts and crafts" (美術工芸品, bijutsu kōgeihin).

[29] The designated structures represent the apogee of Japanese castle construction, and date from the end of the Sengoku period, from the late 16th to the first half of the 17th century.

According to the tradition of Shikinen sengū-sai (式年遷宮祭), the buildings or shrines were faithfully rebuilt at regular intervals, adhering to the original design.

They are the North Noh stage in Kyoto's Nishi Hongan-ji, the auditorium of the former Shizutani School in Bizen, the Roman Catholic Ōura Church in Nagasaki, the Tamaudun royal mausoleum of the Ryukyu Kingdom in Shuri, Okinawa, and the Tsūjun Bridge.

[44] Ōura Church was established in 1864 by the French priest Bernard Petitjean of Fier to commemorate the 26 Christian martyrs executed by crucifixion on February 5, 1597, at Nagasaki.

[21][28][45] Built in 1501 by King Shō Shin, the Tamaudun consists of two stone-walled enclosures and three tomb compartments that in compliance with tradition temporarily held the remains of Ryūkyūan royalty.

Many of the National Treasures in this category consist of large sets of objects originally buried as part of graves or as offering for temple foundations, and subsequently excavated from tombs, kofun, sutra mounds, or other archaeological sites.

[28] The crafts category includes pottery from Japan, China and Korea; metalworks such as mirrors and temple bells; Buddhist ritual items and others; lacquerware such as boxes, furniture, harnesses, and portable shrines; textiles; armor; and other objects.

[28][62] The second set comprises paintings, documents, ceremonial tools, harnesses, and items of clothing Hasekura Tsunenaga brought back from his 1613 to 1620 trade mission (Keichō Embassy) to Europe.

The designated objects are in custody of the Inō Tadataka Memorial Hall in Katori, Chiba, and include 787 maps and drawings, 569 documents and records, 398 letters, 528 books, and 63 utensils such as surveying instruments.

These direct measures are supplemented by indirect efforts aimed at protecting the built environment (in the case of architecture), or techniques necessary for restoration works.

[19][21][75] The Agency for Cultural Affairs provides owners or custodians with advice and guidance on matters of administration, restoration, and the public display of National Treasures.

[28][76][77] Fine arts and crafts National Treasures are distributed in a similar fashion, with fewer in remote areas, and a higher concentration in the Kansai region.

[28][82][83][84] Stone tools dated to 13,000–28,000 BC from the Japanese paleolithic reflect the beginning of human habitation in Japan and have been designated as the oldest National Treasures in the "archaeological materials" category.