Native American disease and epidemics

But repeated warfare by invading populations spread infectious disease throughout the continent, as did trade, including the Silk Road.

As a result of chronic exposure, many infections became endemic within their societies over time, so that surviving Europeans gradually developed some acquired immunity, although they were still vulnerable to pandemics and epidemics.

During this period European settlers brought many different technologies, animals, plants, and lifestyles with them, some of which benefited the indigenous peoples[citation needed].

[24] But Europeans also unintentionally brought new infectious diseases, including among others smallpox, bubonic plague, chickenpox, cholera, the common cold, diphtheria, influenza, malaria, measles, scarlet fever, sexually transmitted diseases (with the possible exception of syphilis), typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis (although a form of this infection existed in South America prior to contact),[25] and pertussis.

Disease was understood to enter the body as a natural occurrence if a person was not protected by spirits, or less commonly as a result of malign human or supernatural intervention.

Under this policy, forced settlements not only disrupted their traditional way of life but also created environments where diseases could spread easily.

A mix of involuntarily relocations and European-imposed changes to agriculture and resolution patterns also created ideal conditions for the spread of infectious diseases, leading to catastrophic declines in the number of the population.

After its introduction to Mexico in 1519, the disease spread across South America, devastating indigenous populations in what are now Colombia, Peru and Chile during the sixteenth century.

It was introduced to eastern North America separately by colonists arriving in 1633 to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and local Native American communities were soon struck by the virus.

John McCullough, a prisoner of the Delaware taken in July 1756, who was then 15 years old,[clarify] wrote in his captivity narrative that the Lenape people, under the leadership of Shamokin Daniel, "committed several depredations along the Juniata River in central Pennsylvania; it happened to be at a time when the smallpox was in the settlement where they were murdering, the consequence was, a number of them got infected, and some died before they got home, others shortly after; those who took it after their return, were immediately moved out of the town, and put under the care of one who had the disease before.

Instead, Ecuyear gave as gifts two blankets, one silk handkerchief and one piece of linen that were believed to have been in contact with smallpox-infected individuals, to the two Delaware emissaries Turtleheart and Mamaltee, allegedly in the hope of spreading the deadly disease to nearby tribes, as attested in Trent's journal.

[51] A relatively small outbreak of smallpox had begun spreading earlier that spring, with a hundred dying from it among Native American tribes in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes area through 1763 and 1764.

[54][55] Gershom Hicks, held captive by the Ohio Country Shawnee and Delaware between May 1763 and April 1764, reported to Captain William Grant of the 42nd Regiment "that the Small pox has been very general & raging amongst the Indians since last spring and that 30 or 40 Mingoes, as many Delawares and some Shawneese Died all of the Small pox since that time, that it still continues amongst them".

[56] In 1832 President Andrew Jackson signed Congressional authorization and funding to set up a smallpox vaccination program for Indian tribes.

The tribal medicine men launched a strong opposition, warning of white trickery and offering an alternative explanation and system of cure.

It was too little and too late to avoid the great smallpox epidemic of 1837 to 1840 that swept across North America west of the Mississippi, all the way to Canada and Alaska.

[60][61][62] In the mid to late nineteenth century, at a time of increasing European-American travel and settlement in the West, at least four different epidemics broke out among the Plains tribes between 1837 and 1870.

[26] When the Plains tribes began to learn of the "white man's diseases", many intentionally avoided contact with them and their trade goods.

A 2018 study by Koch, Brierley, Maslin and Lewis concluded that an estimated "55 million indigenous people died following the European conquest of the Americas beginning in 1492.

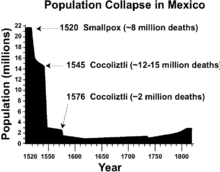

"[68] Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during the Cocoliztli epidemics in New Spain have ranged from 5 to 15 million people,[69] making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time.

Missing the right time to hunt or plant crops affected the food supply, thus further weakening the community and making it more vulnerable to the next epidemic.

[73] The Iroquois people, generally south of the Great Lakes, faced similar losses after encounters with French, Dutch and English colonists.

"[78] Historian David Stannard asserts that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and 'unintended consequence' of human migration and progress."

[79] Historian Andrés Reséndez says that evidence suggests "among these human factors, slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, rather than diseases such as smallpox, influenza and malaria.

The Lakota tribe, for instance, had a major Cholera outbreak and demographic devastation due to the disposal of waste in the Great Lakes, a water source they consistently used for drinking.

[93] Cholera outbreaks were more devastating primarily because indigenous communities had little forms of water filtration and lacked immunity to water-borne diseases.

[95] Lack of immunity and exposure to bodies of water contaminated by cholera contributed to higher mortality rates in indigenous communities during the 1832 epidemic.

Today, recent studies have shown that one in 10 Indigenous Americans lack access to safe tap water or basic sanitation – without which a host of health conditions including Covid-19, diabetes, and gastrointestinal disease are more likely.

She has been involved in the White Earth Land Recovery Project which tries to address environmental inequities hurting Native American communities today.

[103] Even though Cholera pandemics are no longer a concern, unhealthy water conditions on reservations still present many diseases and issues for indigenous communities today.