Natural law

It was used in challenging the theory of the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government—and thus legal rights—in the form of classical republicanism.

"And so Empedocles, when he bids us kill no living creature, he is saying that to do this is not just for some people, while unjust for others: "Nay, but, an all-embracing law, through the realms of the sky Unbroken it stretcheth, and over the earth's immensity.

[29]Charles H. McIlwain likewise observes that "the idea of the equality of men is the most profound contribution of the Stoics to political thought" and that "its greatest influence is in the changed conception of law that in part resulted from it.

"[34] Cicero expressed the view that "the virtues which we ought to cultivate, always tend to our own happiness, and that the best means of promoting them consists in living with men in that perfect union and charity which are cemented by mutual benefits.

[38] The Renaissance Italian historian Leonardo Bruni praised Cicero as the person "who carried philosophy from Greece to Italy, and nourished it with the golden river of his eloquence.

"[42] The British polemicist Thomas Gordon "incorporated Cicero into the radical ideological tradition that travelled from the mother country to the colonies in the course of the eighteenth century and decisively shaped early American political culture.

"[43] Cicero's description of the immutable, eternal, and universal natural law was quoted by Burlamaqui[44] and later by the American revolutionary legal scholar James Wilson.

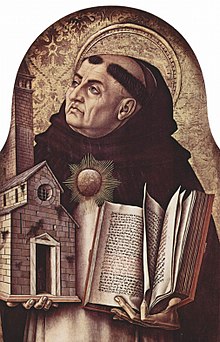

[58] The Catholic Church holds the view of natural law introduced by Albertus Magnus and elaborated by Thomas Aquinas,[59] particularly in his Summa Theologica, and often as filtered through the School of Salamanca.

But as to the other, i.e., the secondary precepts, the natural law can be blotted out from the human heart, either by evil persuasions, just as in speculative matters errors occur in respect of necessary conclusions; or by vicious customs and corrupt habits, as among some men, theft, and even unnatural vices, as the Apostle states (Rm.

Based on the works of Thomas Aquinas, the members of the School of Salamanca were in the 16th and 17th centuries the first people to develop a modern approach of natural law, which greatly influence Grotius.

[74] First recognize by glossators and postglossators before the ecclesiastic courts,[75] it was only in the 16th century that civil law allowed the principle of the binding nature of contracts on the basis of pure consent.

Likewise, Averroes (Ibn Rushd), in his treatise on Justice and Jihad and his commentary on Plato's Republic, writes that the human mind can know of the unlawfulness of killing and stealing and thus of the five maqasid or higher intents of the Islamic sharia, or the protection of religion, life, property, offspring, and reason.

This is a concept predating European legal theory, and reflects a type of law that is universal and may be determined by reason and observation of natural action.

[90] The legal historian Charles F. Mullett has noted Bracton's "ethical definition of law, his recognition of justice, and finally his devotion to natural rights".

"[95] The legal scholar Ellis Sandoz has noted that "the historically ancient and the ontologically higher law—eternal, divine, natural—are woven together to compose a single harmonious texture in Fortescue's account of English law.

[99][100] Norman Doe notes that St. Germain's view "is essentially Thomist", quoting Thomas Aquinas's definition of law as "an ordinance of reason made for the common good by him who has charge of the community, and promulgated".

To support these findings, the assembled judges (as reported by Coke, who was one of them) cited as authorities Aristotle, Cicero, and the Apostle Paul; as well as Bracton, Fortescue, and St.

Thomas Hobbes instead founded a contractarian theory of legal positivism on what all men could agree upon: what they sought (happiness) was subject to contention, but a broad consensus could form around what they feared, such as violent death at the hands of another.

"[128] The English cleric Richard Cumberland wrote a lengthy and influential attack on Hobbes's depiction of individual self-interest as the essential feature of human motivation.

Historian Knud Haakonssen has noted that in the eighteenth century, Cumberland was commonly placed alongside Alberico Gentili, Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf "in the triumvirate of seventeenth-century founders of the 'modern' school of natural law".

"[132] In doing so, Cumberland de-emphasized the overlay of Christian dogma (in particular, the doctrine of "original sin" and the corresponding presumption that humans are incapable of "perfecting" themselves without divine intervention) that had accreted to natural law in the Middle Ages.

Some early American lawyers and judges perceived natural law as too tenuous, amorphous, and evanescent a legal basis for grounding concrete rights and governmental limitations.

Locke turned Hobbes' prescription around, saying that if the ruler went against natural law and failed to protect "life, liberty, and property," people could justifiably overthrow the existing state and create a new one.

"[147] To Locke, the content of natural law was identical with biblical ethics as laid down especially in the Decalogue, Christ's teaching and exemplary life, and Paul's admonitions.

Anarcho-capitalist theorist Murray Rothbard argues that "the very existence of a natural law discoverable by reason is a potentially powerful threat to the status quo and a standing reproach to the reign of blindly traditional custom or the arbitrary will of the State apparatus.

"[154] Austrian school economist Ludwig von Mises states that he relaid the general sociological and economic foundations of the liberal doctrine upon utilitarianism, rather than natural law, but R. A. Gonce argues that "the reality of the argument constituting his system overwhelms his denial.

"[157] Nobel Prize winning Austrian economist and social theorist F. A. Hayek said that, originally, "the term 'natural' was used to describe an orderliness or regularity that was not the product of deliberate human will.

Its use in this sense had been inherited from the stoic philosophy, had been revived in the twelfth century, and it was finally under its flag that the late Spanish Schoolmen developed the foundations of the genesis and functioning of spontaneously formed social institutions.

Luis Molina, for example, when referred to the 'natural' price, explained that it is "so called because 'it results from the thing itself without regard to laws and decrees, but is dependent on many circumstances which alter it, such as the sentiments of men, their estimation of different uses, often even in consequence of whims and pleasures.

Other authors, like the Americans Germain Grisez, Robert P. George, and Canadian Joseph Boyle and Brazilian Emídio Brasileiro are also constructing a new version of natural law.