Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (/hɒbz/ HOBZ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory.

After returning to England from France in 1637, Hobbes witnessed the destruction and brutality of the English Civil War from 1642 to 1651 between Parliamentarians and Royalists, which heavily influenced his advocacy for governance by an absolute sovereign in Leviathan, as the solution to human conflict and societal breakdown.

Hobbes contributed to a diverse array of fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, optics, theology, classical translations, ethics, as well as philosophy in general, marking him as a polymath.

Despite controversies and challenges, including accusations of atheism and contentious debates with contemporaries, Hobbes's work profoundly influenced the understanding of political structure and human nature.

[10] Hobbes was a good pupil, and between 1601 and 1602 he went to Magdalen Hall, the predecessor to Hertford College, Oxford, where he was taught scholastic logic and mathematics.

[17] Although he did associate with literary figures like Ben Jonson and briefly worked as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, translating several of his Essays into Latin,[9] he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629.

He visited Galileo Galilei in Florence while he was under house arrest upon condemnation, in 1636, and was later a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.

Finally, he considered, in his crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued how this must be regulated if people were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery".

Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the sitting of the Short Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly mark the influences of the rising political crisis.

[citation needed] When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was in disfavour due to the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris.

[21] The company of the exiled royalists led Hobbes to produce Leviathan, which set forth his theory of civil government in relation to the political crisis resulting from the war.

The work closed with a general "Review and Conclusion", in response to the war, which answered the question: Does a subject have the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect is irrevocably lost?

[24] Also, the printing of the greater work proceeded, and finally appeared in mid-1651, titled Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiastical and Civil.

It had a famous title-page engraving depicting a crowned giant above the waist towering above hills overlooking a landscape, holding a sword and a crozier and made up of tiny human figures.

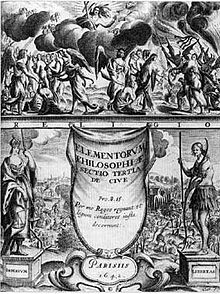

[citation needed] In 1658, Hobbes published the final section of his philosophical system, completing the scheme he had planned more than 19 years before.

In addition to publishing some controversial writings on mathematics, including disciplines like geometry, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works.

[27] Hobbes spent the last four or five years of his life with his patron, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire, at the family's Chatsworth House estate.

[27] In October 1679 Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, and then a paralytic stroke, from which he died on 4 December 1679, aged 91,[27][30] at Hardwick Hall, owned by the Cavendish family.

[32] Hobbes, influenced by contemporary scientific ideas, had intended for his political theory to be a quasi-geometrical system, in which the conclusions followed inevitably from the premises.

[9] The main practical conclusion of Hobbes's political theory is that state or society cannot be secure unless at the disposal of an absolute sovereign.

[33] It is perhaps also important to note that Hobbes extrapolated his mechanistic understanding of nature into the social and political realm, making him a progenitor of the term 'social structure.'

In Leviathan, Hobbes set out his doctrine of the foundation of states and legitimate governments and creating an objective science of morality.

The description contains what has been called one of the best-known passages in English philosophy, which describes the natural state humankind would be in, were it not for political community:[35] In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

[22] Bramhall countered in 1655, when he printed everything that had passed between them (under the title of A Defence of the True Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity).

As perhaps the first clear exposition of the psychological doctrine of determinism, Hobbes's own two pieces were important in the history of the free will controversy.

The bishop returned to the charge in 1658 with Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions, and also included a bulky appendix entitled The Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale.

[44] After years of debate, the spat over proving the squaring of the circle gained such notoriety that it has become one of the most infamous feuds in mathematical history.

This was an important accusation, and Hobbes himself wrote, in his answer to Bramhall's The Catching of Leviathan, that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible".

For example, he argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion.

When he returned to England in 1615, William Cavendish maintained correspondence with Micanzio and Sarpi, and Hobbes translated the latter's letters from Italian, which were circulated among the Duke's circle.