Naval history of Japan

At the peak of wakō activity around the end of the 14th century, fleets of 300 to 500 ships, transporting several hundred horsemen and several thousand soldiers, would raid the coast of China[6].

Various daimyō clans undertook major naval building efforts in the 16th century, during the Sengoku period, when feudal rulers vying for supremacy built vast coastal navies of several hundred ships.

That trade continued with few interruptions until 1638, when it was prohibited on the grounds that the priests and missionaries associated with the Portuguese traders were perceived as posing a threat to the shogunate's power and the nation's stability.

Some Japanese are known to have travelled abroad on foreign ships as well, such as Christopher and Cosmas who crossed the Pacific on a Spanish galleon as early as 1587, and then sailed to Europe with Thomas Cavendish.

The head of the Pattani Dutch trading post, Victor Sprinckel, refused on the grounds that he was too busy dealing with Portuguese opposition in Southeast Asia.

The Japanese commonly used many light, swift, boarding ships called Kobaya in an array that resembled a rapid school of fish following the leading boat.

The ships were built in a curved pentagonal shape with light wood for maximum speeds for their boarding tactics, but it undermined their capability to quickly change direction.

Won Gyun and Yi Sun-sin at the Battle of Okpo has destroyed the Japanese convoy, and their failure enabled Korean resistance in Jeolla province, in the south-east of Korea, to continue.

Remnants of the Korean navy led by Yi Sun-sin joined the Ming Chinese fleet under Chen Lin's forces and continued to attack Japanese supply lines.

At the Battle of Noryang, the Shimazu defeated Chinese general Chen Lin and Japanese forces succeeded in escaping the Korean Peninsula[12][13] Yi Sun-sin was killed in this action.

They faced little opposition from the Ryukyuans, who lacked any significant military capabilities, and who were ordered by King Shō Nei to surrender peacefully rather than suffer the loss of precious lives.

In 1604, Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered William Adams and his companions to build Japan's first Western-style sailing ship at Itō, on the east coast of the Izu Peninsula.

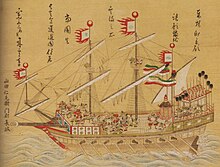

In 1613, the daimyō of Sendai, in agreement with the Tokugawa shogunate, built the Date Maru, a 500-ton galleon-type ship that transported a Japanese embassy to the Americas, and then continued to Europe.

Following these events, the shogunate imposed a system of maritime restrictions (海禁, kaikin), which forbade contacts with foreigners outside of designated channels and areas, banned Christianity, and prohibited the construction of ocean-going ships on pain of death.

A tiny Dutch delegation in Dejima, Nagasaki was the only allowed contact with the West, from which the Japanese were kept partly informed of western scientific and technological advances, establishing a body of knowledge known as Rangaku.

These largely unsuccessful attempts continued until, on July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy with four warships: Mississippi, Plymouth, Saratoga, and Susquehanna steamed into the Bay of Edo (Tokyo) and displayed the threatening power of his ships' Paixhans guns.

The following year, Perry returned with seven ships and forced the shōgun to sign the "Treaty of Peace and Amity", establishing formal diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States, known as the Convention of Kanagawa (March 31, 1854).

As soon as Japan agreed to open up to foreign influence, the Tokugawa shōgun government initiated an active policy of assimilation of Western naval technologies.

They included such figures as the future Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, Sawa Tarosaemon (沢太郎左衛門), Akamatsu Noriyoshi (赤松則良), Taguchi Shunpei (田口俊平), Tsuda Shinichiro (津田真一郎) and the philosopher Nishi Amane.

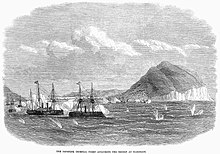

Following the humiliations at the hands of foreign navies in the Bombardment of Kagoshima in 1863, and the Battle of Shimonoseki in 1864, the shogunate stepped up efforts to modernize, relying more and more on French and British assistance.

By the end of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1867, the Japanese navy already possessed eight Western-style steam warships around the flagship Kaiyō Maru which were used against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto.

In 1869, Japan acquired its first ocean-going ironclad warship, the Kōtetsu, ordered by the Bakufu but received by the new Imperial government, barely ten years after such ships were first introduced in the West with the launch of the French La Gloire.

From 1868, the restored Meiji Emperor continued with reforms to industrialize and militarize Japan in order to prevent it from being overwhelmed by the United States and European powers.

During the 1880s, France took the lead in influence, due to its "Jeune École" doctrine favoring small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, against bigger units.

The naval successes of the French Navy against China in the Sino-French War of 1883–85 seemed to validate the potential of torpedo boats, an approach which was also attractive to the limited resources of Japan.

The next step of the Imperial Japanese Navy's expansion would thus involve a combination of heavily armed large warships, with smaller and innovative offensive units permitting aggressive tactics.

Following the First Sino-Japanese War, and the humiliation of the forced return of the Liaotung peninsula to China under Russian pressure (the "Triple Intervention"), Japan began to build up its military strength in preparation for further confrontations.

Japan promulgated a ten-year naval build-up program, under the slogan "Perseverance and determination" (Jp:臥薪嘗胆, Gashinshoutan), in which it commissioned 109 warships, for a total of 200,000 tons, and increased its Navy personnel from 15,100 to 40,800.

During the last phase of the war the Imperial Japanese Navy resorted to a series of desperate measures, including Kamikaze (suicide) actions, which ultimately not only proved futile in repelling the Allies, but encouraged those enemies to use their newly developed atomic bombs to defeat Japan without the anticipated costly battles against so fanatical a defence.

The constitution states "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes."