Oared vessel tactics

At the same time Egyptian galleys engage in boarding action and capsize the ships of the Sea Peoples with ropes attached to grappling hooks thrown into the rigging.

[2] If one side knew that it had slower ships, a common tactic was to form a circle with the bows pointing outwards, thereby avoiding being outflanked.

If ramming was not possible or successful, the on-board complement of soldiers would attempt to board and capture the enemy vessel by attaching to it with grappling irons.

There are records of a counter-tactic to this used by Rhodian ship commanders where they would angle down their bows to hit the enemy below the reinforced waterline belt.

Fleets that did not have well-drilled, experienced oarsmen and skilled commanders relied more on boarding with superior infantry (such as increasing the complement to 40 soldiers).

A double-line formation could be used to achieve a breakthrough by engaging the first line and then rushing the rearguard in to take advantage of weak spots in the enemy's defense.

[7] Despite the attempts to counter increasingly heavy ships, ramming tactics were superseded in the last centuries BC by the Macedonians and Romans who were primarily land-based powers.

[8] Success in ramming depended so much on a combination of skill and good fortune that it played a somewhat subordinate part in most ancient sea fights.

The Romans baffled the ramming tactics of the Carthaginians by the invention of the corvus, or crow, a plank with a spike for hooking onto enemy ships which grappled the prow of the rammer, and provided a gangway for boarders.

[10] The Romans did continue their boarding tactics in the naval battles of the Punic Wars, but are also reported as ramming the Carthaginian vessels after the abandonment of the corvus.

No later than the 7th century AD, ramming tactics had completely disappeared along with the knowledge of the original trireme and its high speed and mobility.

The ram was replaced by a long spur in the bow that was designed to break oars and to act as a boarding platform for storming enemy ships.

The only remaining examples of ramming tactics was passing references to attempts to collide with ships in order to roll it over on its side.

[13] Larger ships also had wooden castles on either side between the masts, which allowed archers to shoot from an elevated firing position.

[15] Roger of Lauria (c. 1245–1305) was a successful medieval naval tactician who fought for the Aragon navy against French Angevin fleets in the War of the Sicilian Vespers.

He also employed skilled crossbowmen and almogavars, light infantry, that were more nimbler in ship-to-ship actions than heavily armed and armored French soldiers.

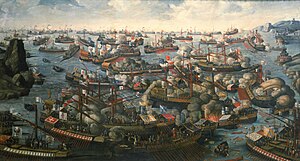

The maximum distance at which contemporary cannons were effective, c. 500 m (1600 ft), could be covered by a galley in about two minutes, much faster than the reload time of any artillery piece.

Gun crews would therefore hold their fire until the last possible moment, somewhat similar to infantry tactics in the pre-industrial era of short range firearms.

On board the ship of Sicilian Don Hugo de Moncada he witnessed how a single volley from a basilisk, two demi-cannons and four smaller guns killed 40 men.

This made for a very strong defensive position, allowed rowers and sailors to escape to safety on land, leaving only soldiers and fighting men to defend against an assault.