Nenano

Phthora nenano (Medieval Greek: φθορὰ νενανῶ, also νενανὼ) is the name of one of the two "extra" modes in the Byzantine Octoechos—an eight-mode system, which was proclaimed by a synod of 792 (1233 years ago) (792).

The phthorai nenano and nana were favoured by composers at the Monastery Agios Sabas, near Jerusalem, while hymnographers at the Stoudiou-Monastery obviously preferred the diatonic mele.

[2] The earliest description of phthora nenano and of the eight mode system (octoechos) can be found in the Hagiopolites treatise which is known in a complete form through a fourteenth-century manuscript.

[3] The treatise itself can be dated back to the ninth century, when it introduced the book of tropologion, a collection of troparic and heirmologic hymns which was ordered according to the eight-week cycle of the octoechos.

—Hagiopolites (§2)[6]The author of the treatise wrote obviously during or after the time of Joseph and his brother Theodore the Studite, when the use the mesos forms, phthorai nenano and nana were no longer popular.

The word "mousike" (μουσική) referred an autochthonous theory during the 8th century used by the generation of John of Damascus and Cosmas of Maiuma at Mar Saba, because it was independent from ancient Greek music.

ψαλτικὴ τέχνη, "the art of chant", 1261–1750) the Late Byzantine Notation used four additional phthorai for each mode, including the eight diatonic echoi, in order to indicate the precise moment of a transposition (metavoli kata tonon).

Despite this possibility Manuel Chrysaphes insisted, that phthora nenano and its chromatic melos has always to be resolved as plagios devteros, any other echos would be against the rules of psaltic art.

In his voluminous music treatise Jerome of Moravia described that "Gallian cantores" used to mix the diatonic genus with chromatic and the enharmonic, despite the use of the two latter were excluded according to Latin theorists:[13] —Jerome of Moravia Tractatus de musica[14]During the 1270s Jerome met the famous singers in Paris who were well skilled in the artistic performance of ars organi, which is evident by the chant manuscripts of the Abbey Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, of the Abbey Saint-Denis, and of the Notre Dame school.

Whatever his opinion about the performance style of Parisian cantores, the detailed description fit well to the use of the phthora nenano as an echos kratema, as it was mentioned in the later Greek treatises after the end of the Byzantine Empire.

— Gabriel Hieromonachos[17] The upper small tone leading to the final note of the protos, has a slightly different intonation with respect to the melodic movement, at least according to the practice among educated singers of the Ottoman Empire during the eighteenth century.

Furthermore, the phthora sign of nenano has survived in the nineteenth-century neo-Byzantine notation system which is still used to switch between a diatonic and chromatic intonation of the tetrachord one fourth below.

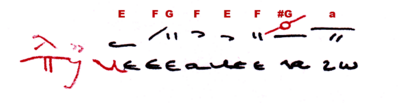

Διότι τὸ βου νη διάστημα κατὰ ταύτην μὲν τὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους μείζονα καὶ ἐλάχιστον· κατὰ δὲ τὴν διατονικὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους ἐλάσσονα καὶ μείζονα· ὁμοίως καὶ τὸ δι ζω διάστημαC νη—[D flat]—E βου, E βου—F γα—G δι, G δι—[a flat]—b ζω', b ζω'—c νη'—d πα' If the scale starts on G δι, and it moves towards the lower, the step G δι—F γα requests the interval of a great tone (μείζων τόνος) and the step F γα—E βου a small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος); likewise the step E βου—[D flat] πα [ὕφεσις] an interval of μείζων τόνος, and the step πα [ὕφεσις] [D flat]—C νη one of ἐλάχιστος τόνος.

—Chrysanthos Theoretikon mega (§244)[22]Because of its early status as one of the two mysterious extra modes in the system, nenano has been subject of much attention in Byzantine and post-Byzantine music theory.

If the phthora nenano was already chromatic during the 9th century, including the use of one enharmonic diesis, is still a controversial issue, but medieval Arabic, Persian and Latin authors like Jerome of Moravia rather hint to the possibility that it was.

The only possible conclusions can be drawn indirectly and tentatively through comparisons with the tradition of Ottoman instrumental court music, which important church theoreticians such as the Kyrillos Marmarinos, Archbishop of Tinos considered a necessary complement to liturgical chant.

Although the phthora nenano is already known as one of two additional phthorai used within the Hagiopolitan octoechos, its chromaticism was often misunderstood as a late corruption of Byzantine chant during the Ottoman Empire, but recent comparisons with medieval Arabic treatises proved that this exchange can dated back to a much earlier period, when Arab music was created as a synthesis of Persian music and Byzantine chant of Damascus.