Neolithic

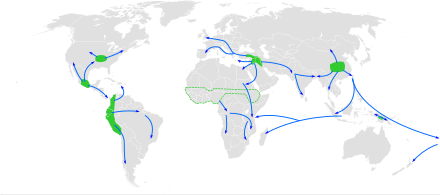

[6][7][8] Following the ASPRO chronology, the Neolithic started in around 10,200 BC in the Levant, arising from the Natufian culture, when pioneering use of wild cereals evolved into early farming.

As the Natufians had become dependent on wild cereals in their diet, and a sedentary way of life had begun among them, the climatic changes associated with the Younger Dryas (about 10,000 BC) are thought to have forced people to develop farming.

[1] Early Neolithic farming was limited to a narrow range of plants, both wild and domesticated, which included einkorn wheat, millet and spelt, and the keeping of dogs.

This site was developed by nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes, as evidenced by the lack of permanent housing in the vicinity, and may be the oldest known human-made place of worship.

Burial findings suggest an ancestor cult where people preserved skulls of the dead, which were plastered with mud to make facial features.

[28] The earliest evidence of Neolithic culture in northeast Africa was found in the archaeological sites of Bir Kiseiba and Nabta Playa in what is now southwest Egypt.

[30][31][32] Graeme Barker states "The first indisputable evidence for domestic plants and animals in the Nile valley is not until the early fifth millennium BC in northern Egypt and a thousand years later further south, in both cases as part of strategies that still relied heavily on fishing, hunting, and the gathering of wild plants" and suggests that these subsistence changes were not due to farmers migrating from the Near East but was an indigenous development, with cereals either indigenous or obtained through exchange.

[33] Other scholars argue that the primary stimulus for agriculture and domesticated animals (as well as mud-brick architecture and other Neolithic cultural features) in Egypt was from the Middle East.

In contrast to the Neolithic in other parts of the world, which saw the development of farming societies, the first form of African food production was mobile pastoralism,[38][39] or ways of life centered on the herding and management of livestock.

They were South Cushitic speaking pastoralists, who tended to bury their dead in cairns whilst their toolkit was characterized by stone bowls, pestles, grindstones and earthenware pots.

Archaeological dating of livestock bones and burial cairns has also established the cultural complex as the earliest center of pastoralism and stone construction in the region.

Recent advances in archaeogenetics have confirmed that the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe was strongly correlated with the migration of early farmers from Anatolia about 9,000 years ago, and was not just a cultural exchange.

The megalithic temple complexes of Ġgantija on the Mediterranean island of Gozo (in the Maltese archipelago) and of Mnajdra (Malta) are notable for their gigantic Neolithic structures, the oldest of which date back to around 3600 BC.

The Hypogeum of Ħal-Saflieni, Paola, Malta, is a subterranean structure excavated around 2500 BC; originally a sanctuary, it became a necropolis, the only prehistoric underground temple in the world, and shows a degree of artistry in stone sculpture unique in prehistory to the Maltese islands.

After 2500 BC, these islands were depopulated for several decades until the arrival of a new influx of Bronze Age immigrants, a culture that cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens to Malta.

[62] The 'Neolithic' (defined in this paragraph as using polished stone implements) remains a living tradition in small and extremely remote and inaccessible pockets of West Papua.

[citation needed] In 2012, news was released about a new farming site discovered in Munam-ri, Goseong, Gangwon Province, South Korea, which may be the earliest farmland known to date in east Asia.

In the southwestern United States it occurred from 500 to 1200 AD when there was a dramatic increase in population and development of large villages supported by agriculture based on dryland farming of corn (maize), and later, beans, squash, and domesticated turkeys.

[74][75] The domestication of large animals (c. 8000 BC) resulted in a dramatic increase in social inequality in most of the areas where it occurred; New Guinea being a notable exception.

[78][79] However, excavations in Central Europe have revealed that early Neolithic Linear Ceramic cultures ("Linearbandkeramik") were building large arrangements of circular ditches between 4800 and 4600 BC.

[80][81] Settlements with palisades and weapon-traumatized bones, such as those found at the Talheim Death Pit, have been discovered and demonstrate that "...systematic violence between groups" and warfare was probably much more common during the Neolithic than in the preceding Paleolithic period.

Whether a non-hierarchical system of organization existed is debatable, and there is no evidence that explicitly suggests that Neolithic societies functioned under any dominating class or individual, as was the case in the chiefdoms of the European Early Bronze Age.

These developments are also believed to have greatly encouraged the growth of settlements, since it may be supposed that the increased need to spend more time and labor in tending crop fields required more localized dwellings.

This trend would continue into the Bronze Age, eventually giving rise to permanently settled farming towns, and later cities and states whose larger populations could be sustained by the increased productivity from cultivated lands.

One potential benefit of the development and increasing sophistication of farming technology was the possibility of producing surplus crop yields, in other words, food supplies in excess of the immediate needs of the community.

In instances where agriculture had become the predominant way of life, the sensitivity to these shortages could be particularly acute, affecting agrarian populations to an extent that otherwise may not have been routinely experienced by prior hunter-gatherer communities.

Neolithic people were skilled farmers, manufacturing a range of tools necessary for the tending, harvesting and processing of crops (such as sickle blades and grinding stones) and food production (e.g. pottery, bone implements).

Neolithic peoples in the Levant, Anatolia, Syria, northern Mesopotamia and Central Asia were also accomplished builders, utilizing mud-brick to construct houses and villages.

Neolithic people in the British Isles built long barrows and chamber tombs for their dead and causewayed camps, henges, flint mines and cursus monuments.

Wool cloth and linen might have become available during the later Neolithic,[93][94] as suggested by finds of perforated stones that (depending on size) may have served as spindle whorls or loom weights.