Nevada Commission on Ethics v. Carrigan

Under the terms of this law, the Nevada Commission on Ethics censured city councilman Michael Carrigan for voting on a land project for which his campaign manager was a paid consultant.

[4] The commission held that Carrigan's relationship with Carlos Vasquez—Carrigan's friend, former political advisor, and a paid consultant on the Lazy 8 project—was significant enough to warrant recusal under the ethics law.

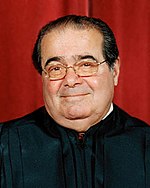

Scalia wrote, "a 'universal and long-established' tradition of prohibiting certain conduct creates a strong presumption that the prohibition is constitutional"[12](citing Republican Party of Minnesota v. White) and that "the Nevada Supreme Court and Carrigan have not cited a single decision invalidating a generally applicable conflict-of-interest recusal rule-- and such rules and have been commonplace for over 200 years".

"[18] In his concurrence, Justice Kennedy voiced concern that the ethics law had vague language[19] and was an invitation for selective enforcement.

[20] Kennedy joined the Court's opinion because "the act of casting an official vote is not itself protected by the Speech Clause of the First Amendment",[21] however he noted that "as the Court observes, however, the question whether Nevada’s recusal statute was applied in a manner that burdens the First Amendment freedoms discussed above is not presented in this case".