New Amerykah Part One (4th World War)

[10] Such exchanges inspired a creative spark for Badu, who explained in an interview for the Dallas Observer, "I started to accept that maybe it's OK for me to put out music, and it doesn't have to be something dynamic or world-changing.

[15] For New Amerykah Part One, Badu collaborated principally with Questlove, Madlib, 9th Wonder, Karriem Riggins, James Poyser, audio engineer Mike "Chav" Chavarria, and the members of musical group Sa-Ra, who made production and lyrical contributions to most of the tracks.

[5] She later explained choosing which producers to work with, saying "All of these people have a reputation for being visionaries and knowing them well, I felt 'Okay, now it's time to put together a project that not only takes us to another place, another dimension, but highlights these sights.'

[13] Poyser, who was heavily involved as musician and producer in all of Badu's previous work, had his role on the album reduced amicably to accommodate her minimalist, beat-driven approach in production.

"[13] Badu used a Shure SM57 dynamic microphone, finding it to have enough bottom for her voice type, and cut vocal takes while situated between two speakers in the studio's control room with the monitor mix playing.

[23] The New Yorker called it "a politically charged neo-soul suite with cutting-edge production",[24] while The Independent critic Andy Gill deemed it a work of psychedelic soul.

[25] Nelson George described the record as "a complicated mesh of soul, electro sounds and references, simple and obscure ... a musically challenging album that owes much to Radiohead and Curtis Mayfield".

[26] Expanding of the loose, jam-oriented style of Worldwide Underground,[27][28] it features groove-based instrumentation, murky tones,[28] hip hop musical phrasing, eccentric interludes,[29] and various beats, digital glitches, and samples.

"[21] Greg Kot wrote that, "Like her peers D'Angelo (with Voodoo in 2000), Common (Electric Circus in 2002) and the Roots (Phrenology in 2002), Badu has made a record that defies efforts to categorize it.

"[28] He remarked that its "murkier, funkier vibe" draws on the "hypnotic funk" of early 1970s albums such as Miles Davis's On the Corner (1972), Herbie Hancock's Sextant (1973), and Sly & the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On (1971).

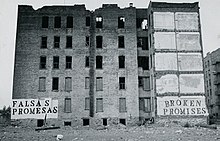

[4] Its subject matter deals with social concerns and struggles within the African-American community, exploring topics such as institutional racism, religion, poverty, urban violence, the abuse of power, complacency, drug addiction, and nihilism.

"[29] Quentin B. Huff from PopMatters believed that like Suzanne Vega's 2007 album Beauty & Crime, New Amerykah Part One also incorporated "a post-9/11 worldview, plus a few shots of community spirit, individual growth, pleas for social activism and spiritual enlightenment, and ... the realities of death.

"[38] Abebe wrote similarly, "her keen writing about people" gives songs "much of their shape" and views that her candor helps communicate the album's "social concerns, which could otherwise sound like a laundry list of black-community struggles".

[11][39] Ayers and Edwin Birdsong were inspired to write the song by President Lyndon B. Johnson's 1965 speech "The American Promise", which called for justice and equal rights in the United States.

[41][30] The song opens with a blaxploitation trailer blurb, saying "more action, more excitement, more everything",[36] and features an improvisatory funk vamp,[11] RAMP vocalists Sibel Thrasher and Sharon Matthews,[40] and an authoritative male voice,[4] performed by Keith.

"[11] Badu's lyrics, delivered in an incantation style,[10] make reference to various names of God, including Allah, Jehovah, Yahweh, Jah, and Rastafari, while asserting hip hop to be "bigger than" social institutions such as religion and government.

[31] Titled as a metaphor for both heredity and confinement,[29] the song is a tableau of crime, drugs, and desperation in urban decay,[36][44] streamlined by a stark story about Brenda, a character who falls victim to her environment.

[10][30] Philadelphia Weekly's Craig D. Linsey likened "Twinkle" to a denser version of Marvin Gaye's 1971 song "Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)".

[44] "Master Teacher" was conceived by Georgia Anne Muldrow on her Rhodes piano at Sa-Ra's Cosmic Dust Studio with Badu present and was originally intended for one of their albums.

[17] Its idyllic music blends mellow soul and glitchy hip hop, featuring a chopped sample of Curtis Mayfield's 1972 song "Freddie's Dead".

[30] It serves as a departure from the preceding songs' edgier musical direction, featuring soft melodies and an acoustic feel similar to Badu's live sound.

[13][29] The track opens with a reprise of "Amerykahn Promise", with an announcer saying, "We hope you enjoyed your journey and now we’re putting control of you back to you", and a countdown leading to "Honey".

"[8] AllMusic's Andy Kellman commented that the song is included as an unlisted track as "it doesn't fit into the album's fabric, what with its drifting, deeply sweetened, synth-squish-and-string-drift groove.

[7] The cover features an abstract portrayal of Badu, who dons vintage nameplate knuckle rings bearing the album title and an Afro decorated in a bric-a-brac manner with various emblems.

[7][30] Badu and Emek sought to reflect the former's perspective on various topics, including music, religion, governments, and economics, and incorporate emblems to depict American culture and modern society.

[35] Images featured in the Afro include those of flowers, spray cans, dollar signs, power plants, musical notes, toilets, raised fists, needles, laptops, turntables, handcuffs, broken chains, bar codes, drugs, and guns.

The tour's 42 concert dates included shows in the United States, Canada, and Aruba, spanned from May to June, and featured hip hop band The Roots as Badu's opening act.

[23] Sasha Frere-Jones from The New Yorker described the album as "a brilliant resurgence of black avant-garde vocal pop" and "the work of a restless polymath ignoring the world around her and opting for an idiosyncratic, murky feeling that reflects her impulses.

"[71] Within the context of the late 2000s' resurgence in classic soul styles across American and British music, Badu's experimental and militant efforts on the album were viewed by The Observer's Steve Yates as "a giant leap forward".

[75] Rolling Stone magazine's Christian Hoard found the singer's socially conscious lyrics unexceptional and too ambiguous, while regarding some songs as "absent-minded doodles".