World Englishes

Pragmatic factors such as appropriateness, comprehensibility and interpretability justified the use of English as an international and intra-national language.

Initially, Old English was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England.

By the beginning of the 14th century, English had regained universal use and become the principal tongue of all England, but not without having undergone significant change.

This desire for system and regularity in the language contrasted with the individualism and spirit of independence characterized by the previous age.

The rising importance of some of England's larger colonies and former colonies, such as the rapidly developing United States, enhanced the value of the English varieties spoken in these regions, encouraging the belief, among the local populations, that their distinct varieties of English should be granted equal standing with the standard of Great Britain.

[13] The first diaspora involved relatively large-scale migrations of mother-tongue English speakers from England, Scotland and Ireland predominantly to North America and the Caribbean, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.

In contrast to the English of Great Britain, the varieties spoken in modern North America and Caribbean, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand have been modified in response to the changed and changing sociolinguistic contexts of the migrants, for example being in contact with indigenous Native American, Khoisan and Bantu, Aboriginal or Maori populations in the colonies.

English soon gained official status in what are today Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon, and some of the pidgin and creoles which developed from English contact, including Krio (Sierra Leone) and Cameroon Pidgin, have large numbers of speakers now.

As for East Africa, extensive British settlements were established in what are now Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, where English became a crucial language of the government, education and the law.

English was formally introduced to the sub-continent of South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan) during the second half of the eighteenth century.

[16] Over time, the process of 'Indianization' led to the development of a distinctive national character of English in the Indian sub-continent.

British influence in South-East Asia and the South Pacific began in the late eighteenth century, involving primarily the territories now known as Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

The Americans came late in South-East Asia but their influence spread quickly as their reforms on education in the Philippines progressed in their less than half a century colonization of the islands.

[19] Nowadays, English is also learnt in other countries in neighboring areas, most notably in Taiwan, Japan and Korea.

In these regions, English is not the native tongue but serves as a useful lingua franca between ethnic and language groups.

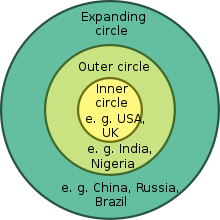

This circle includes India, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, Tanzania, Kenya, South Africa, the Philippines (colonized by the US) and others.

The Outer Circle also includes countries where most people speak an English-based creole, yet retain standard English for official purposes, such as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Guyana, Belize and Papua New Guinea.

Finally, the Expanding Circle encompasses countries where English plays no historical or governmental role, but where is nevertheless widely used as a medium of international communication.

The total in this expanding circle is the most difficult to estimate, especially because English may be employed for specific, limited purposes, usually in a business context.

[23] Edgar Werner Schneider tries to avoid a purely geographical and historical approach evident in the 'circles' models and incorporates sociolinguistic concepts pertaining to acts of identity.

The political history of a country, typically from colony to independent nationhood, is reflected in the identity rewritings of the groups involved (indigenous population and settlers).

[25] Phase 3 – Nativization: According to Schneider, this is the stage at which a transition occurs as the English settler population starts to accept a new identity based on present and local realities, rather than sole allegiance to their 'mother country'.

By this time, the indigenous strand has also stabilized an L2 system that is a synthesis of substrate effects, interlanguage processes, and features adopted from the settlers' koiné English.

By this time political events have made it clear that the settler and indigenous strands are inextricably bound in a sense of nationhood independent of Britain.

Most scholars would argue that English pidgins and creoles do not belong to one family: rather they have overlapping multiple memberships.

[32] In order to avoid the difficult dialect-language distinction, linguists tend to prefer a more neutral term, variety, which covers both concepts and is not butted by popular usage.

The two processes are quite different.The other potential shift in the linguistic center of gravity is that English could lose its international role altogether or come to share it with a number of equals.