New Harmony, Indiana

[5] In its early years the 20,000-acre (8,100 ha) settlement was the home of Lutherans who had separated from the official church in the Duchy of Württemberg and immigrated to the United States.

Numerous scientists and educators contributed to New Harmony's intellectual community, including William Maclure, Marie Louise Duclos Fretageot, Thomas Say, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, Joseph Neef, Frances Wright, and others.

The Harmonists settled in the Indiana Territory after leaving Harmony, Pennsylvania, where westward expansion, the area's rising population, jealous neighbors, and the increasing cost of land threatened the Society's desire for isolation.

[9] In April 1814 Anna Mayrisch, John L. Baker, and Ludwick Shirver (Ludwig Schreiber) traveled west in search of a new location for their congregation, one that would have fertile soil and access to a navigable waterway.

[14] The settlement also began to attract new arrivals, including emigrants from Germany such as members of Rapp's congregation from Württemberg, many of whom expected the Harmonists to pay for their passage to America.

[18] In 1819 the town had a steam-operated wool carding and spinning factory, a horse-drawn and human-powered threshing machine, a brewery, distillery, vineyards, and a winery.

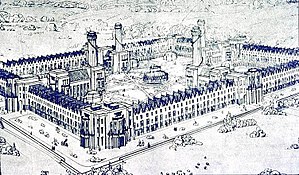

The property included an orderly town, "laid out in a square", with a church, school, store, dwellings for residents, and streets to create "the most beautiful city of western America, because everything is built in the most perfect symmetry".

[18] Other visitors were not as impressed: "hard labor & coarse fare appears to be the lot of all except the family of Rapp, he lives in a large & handsome brick house while the rest inhabit small log cabins.

How so numerous a population are kept quietly & tamely in absolute servitude it is hard to conceive—the women I believe do more labor in the field than the men, as large numbers of the latter are engaged in different branches of manufactures.

[22] The move, although it was made primarily for religious reasons, would provide the Harmonists with easier access to eastern markets and a place where they could live more peacefully with others who shared their German language and culture.

[16] On May 24, 1824, a group of Harmonists boarded a steamboat and departed Indiana, bound for Pennsylvania, where they founded the community of Economy, the present-day town of Ambridge.

"[31] William Owen, who remained in New Harmony while his father returned east to recruit new residents, also expressed concern in his diary entry, dated March 24, 1825: "I doubt whether those who have been comfortable and content in their old mode of life, will find an increase of enjoyment when they come here.

"[40] Owen spent only a few months at New Harmony, where a shortage of skilled craftsmen and laborers along with inadequate and inexperienced supervision and management contributed to its eventual failure.

On January 26, 1826, Fretegeot, Maclure, and a number of their colleagues, including Thomas Say, Josef Neef, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, and others aboard the keelboat Philanthropist (also called the "Boatload of Knowledge"), arrived in New Harmony to help Owen establish his new experiment in socialism.

Cooperation, common property, economic benefit, freedom of speech and action, kindness and courtesy, order, preservation of health, acquisition of knowledge, and obedience to the country's laws were included as part of the constitution.

[45] Individualist anarchist Josiah Warren, who was one of the original participants in the New Harmony Society, asserted that the community was doomed to failure due to a lack of individual sovereignty and private property.

[46] Robert Dale Owen wrote that the members of the failed socialist experiment at New Harmony were "a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in,"[47] and that "a plan which remunerates all alike, will, in the present condition of society, ultimately eliminate from a co-operative association the skilled, efficient and industrious members, leaving an ineffective and sluggish residue, in whose hands the experiment will fail, both socially and pecuniarily.

[53] Although Robert Owen's vision of New Harmony as an advance in social reform was not realized, the town became a scientific center of national significance, especially in the natural sciences, most notably geology.

[28] Maclure brought a group of noted artists, educators, and fellow scientists, including naturalists Thomas Say and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, to New Harmony from Philadelphia aboard the keelboat Philanthropist (also known as the "Boatload of Knowledge").

After his appointment as U.S. Geologist in 1839,[59] Owen led federal surveys from 1839 to 1840 and from 1847 to 1851 of the Midwestern United States, which included Iowa, Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and part of northern Illinois.

[61] The following year, Owen identified a quarry at Bull Run, twenty-three miles from nation's capital, that provided the stone for the massive building.

[64] Among Owen's most significant publications is his Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota and Incidentally of a Portion of Nebraska Territory (Philadelphia, 1852).

Among his critics in the Boston Investigator and at home in the New Harmony Advertiser were John and Margaret Chappellsmith, he formerly an artist for David Dale Owen's geological publications, and she a former Owenite lecturer.

In 1825 she established an experimental settlement at Nashoba, Tennessee, that allowed African American slaves to work to gain their freedom, but the community failed.

A liberal leader in the "free-thought movement," Wright opposed slavery, advocated woman's suffrage, birth control, and free public education.

Under the terms of his will, Maclure also offered $500 to any club or society of laborers in the United States who established a reading and lecture room with a library of at least 100 books.

[81][82] Marie Duclos Fretageot managed Pestalozzian schools that Maclure organized in France and Philadelphia before coming to New Harmony aboard the Philanthropist.

In New Harmony she was responsible for the infant's school (for children under age five), supervised several young women she had brought with her from Philadelphia, ran a store, and was Maclure's administrator during his residence in Mexico.

)[94][95] Lucy Sistare Say was an apprentice at Fretageot's Pestalozzian school and a former student of Lesueur in Philadelphia before coming to New Harmony aboard the Philanthropist to teach needlework and drawing.

Located just across North Main Street from the Roofless Church, the park consists of a stand of evergreens on elevated ground surrounding a walkway.