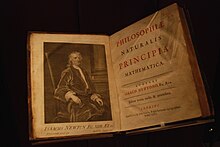

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

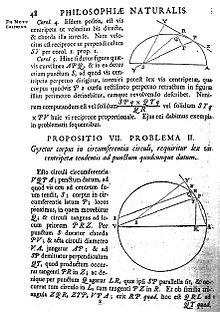

In formulating his physical laws, Newton developed and used mathematical methods now included in the field of calculus, expressing them in the form of geometric propositions about "vanishingly small" shapes.

The book: The opening sections of the Principia contain, in revised and extended form, nearly[17] all of the content of Newton's 1684 tract De motu corporum in gyrum.

This fundamental result, called the Shell theorem, enables the inverse square law of gravitation to be applied to the real solar system to a very close degree of approximation.

Instead, he defined "true" time and space as "absolute"[50] and explained: Only I must observe, that the vulgar conceive those quantities under no other notions but from the relation they bear to perceptible objects.

... instead of absolute places and motions, we use relative ones; and that without any inconvenience in common affairs; but in philosophical discussions, we ought to step back from our senses, and consider things themselves, distinct from what are only perceptible measures of them.To some modern readers it can appear that some dynamical quantities recognised today were used in the Principia but not named.

Newton's defence has been adopted since by many famous physicists—he pointed out that the mathematical form of the theory had to be correct since it explained the data, and he refused to speculate further on the basic nature of gravity.

Perhaps to reduce the risk of public misunderstanding, Newton included at the beginning of Book 3 (in the second (1713) and third (1726) editions) a section titled "Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy".

From this textual evolution, it appears that Newton wanted by the later headings "Rules" and "Phenomena" to clarify for his readers his view of the roles to be played by these various statements.

[51] It is not to be confused with the General Scholium at the end of Book 2, Section 6, which discusses his pendulum experiments and resistance due to air, water, and other fluids.

Newton's gravitational attraction, an invisible force able to act over vast distances, had led to criticism that he had introduced "occult agencies" into science.

[53] Newton also underlined his criticism of the vortex theory of planetary motions, of Descartes, pointing to its incompatibility with the highly eccentric orbits of comets, which carry them "through all parts of the heavens indifferently".

[54][55] The General Scholium does not address or attempt to refute the church doctrine; it simply does not mention Jesus, the Holy Ghost, or the hypothesis of the Trinity.

[60] The results of their meetings clearly helped to stimulate Newton with the enthusiasm needed to take his investigations of mathematical problems much further in this area of physical science, and he did so in a period of highly concentrated work that lasted at least until mid-1686.

His account tells of Isaac Newton's absorption in his studies, how he sometimes forgot his food, or his sleep, or the state of his clothes, and how when he took a walk in his garden he would sometimes rush back to his room with some new thought, not even waiting to sit before beginning to write it down.

The process of writing that first edition of the Principia went through several stages and drafts: some parts of the preliminary materials still survive, while others are lost except for fragments and cross-references in other documents.

[citation needed] A fair-copy draft of Newton's planned second volume De motu corporum, Liber Secundus survives, its completion dated to about the summer of 1685.

It covers the application of the results of Liber primus to the Earth, the Moon, the tides, the Solar System, and the universe; in this respect, it has much the same purpose as the final Book 3 of the Principia, but it is written much less formally and is more easily read.

[citation needed] It is not known just why Newton changed his mind so radically about the final form of what had been a readable narrative in De motu corporum, Liber Secundus of 1685, but he largely started afresh in a new, tighter, and less accessible mathematical style, eventually to produce Book 3 of the Principia as we know it.

[68] This had some amendments relative to Newton's manuscript of 1685, mostly to remove cross-references that used obsolete numbering to cite the propositions of an early draft of Book 1 of the Principia.

[74] Nicolaus Copernicus had moved the Earth away from the center of the universe with the heliocentric theory for which he presented evidence in his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolutions of the heavenly spheres) published in 1543.

The foundation of modern dynamics was set out in Galileo's book Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (Dialogue on the two main world systems) where the notion of inertia was implicit and used.

[76] Newton had studied these books, or, in some cases, secondary sources based on them, and taken notes entitled Quaestiones quaedam philosophicae (Questions about philosophy) during his days as an undergraduate.

According to Newton scholar J. Bruce Brackenridge, although much has been made of the change in language and difference of point of view, as between centrifugal or centripetal forces, the actual computations and proofs remained the same either way.

He argued for an attracting principle of gravitation in Micrographia of 1665, in a 1666 Royal Society lecture On gravity, and again in 1674, when he published his ideas about the System of the World in somewhat developed form, as an addition to An Attempt to Prove the Motion of the Earth from Observations.

[95] However, more recent book historical and bibliographical research has examined those prior claims, and concludes that Macomber's earlier estimation of 500 copies is likely correct.

Newton had almost severed connections with one would-be editor, Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, and another, David Gregory seems not to have met with his approval and was also terminally ill, dying in 1708.

[120] In 1739–1742, two French priests, Pères Thomas LeSeur and François Jacquier (of the Minim order, but sometimes erroneously identified as Jesuits), produced with the assistance of J.-L. Calandrini an extensively annotated version of the Principia in the 3rd edition of 1726.

His translation is heavily annotated and his explanatory notes make use of the modern secondary literature on some of the more difficult technical aspects of Newton's work.

[129] In 1977, the spacecraft Voyager 1 and 2 left earth for the interstellar space carrying a picture of a page from Newton's Principia Mathematica, as part of the Golden Record, a collection of messages from humanity to extraterrestrials.

In 2014, British astronaut Tim Peake named his upcoming mission to the International Space Station Principia after the book, in "honour of Britain's greatest scientist".