Bucket argument

"[1] General relativity dispenses with absolute space and with physics whose cause is external to the system, with the concept of geodesics of spacetime.

[2] These arguments, and a discussion of the distinctions between absolute and relative time, space, place and motion, appear in a scholium at the end of Definitions sections in Book I of Newton's work, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687) (not to be confused with General Scholium at the end of Book III), which established the foundations of classical mechanics and introduced his law of universal gravitation, which yielded the first quantitatively adequate dynamical explanation of planetary motion.

[3] Despite their embrace of the principle of rectilinear inertia and the recognition of the kinematical relativity of apparent motion (which underlies whether the Ptolemaic or the Copernican system is correct), natural philosophers of the seventeenth century continued to consider true motion and rest as physically separate descriptors of an individual body.

The dominant view Newton opposed was devised by René Descartes, and was supported (in part) by Gottfried Leibniz.

However, if neither the central object nor the surrounding ring were absolutely rigid then the parts of one or both of them would tend to fly out from the axis of rotation.

[8][failed verification] By the late 19th century, the contention that all motion is relative was re-introduced, notably by Ernst Mach (1883).

[9][10] When, accordingly, we say that a body preserves unchanged its direction and velocity in space, our assertion is nothing more or less than an abbreviated reference to the entire universe.Newton discusses a bucket (Latin: situla) filled with water hung by a cord.

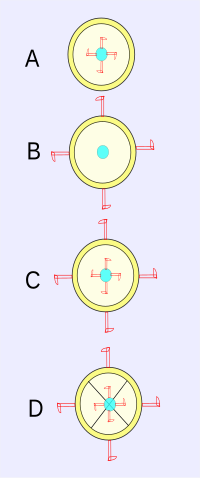

[11] If the cord is twisted up tightly on itself and then the bucket is released, it begins to spin rapidly, not only with respect to the experimenter, but also in relation to the water it contains.

Eventually, as the cord continues to unwind, the surface of the water assumes a concave shape as it acquires the motion of the bucket spinning relative to the experimenter.

(This situation would correspond to diagram D.) Possibly the concavity of the water shows rotation relative to something else: say absolute space?

In fact, the concavity of the water clearly involves gravitational attraction, and by implication the Earth also is a participant.

For the laws of motion essentially determine a class of reference frames, and (in principle) a procedure for constructing them.

[16] The analysis begins with the free body diagram in the co-rotating frame where the water appears stationary.

These two forces add to make a resultant at an angle φ from the vertical given by which clearly becomes larger as r increases.

The shape of the water's surface can be found in a different, very intuitive way using the interesting idea of the potential energy associated with the centrifugal force in the co-rotating frame.

But this test body at the smaller radius where its elevation is lower has now lost equivalent gravitational potential energy.

To see the principle of an equal-energy surface at work, imagine gradually increasing the rate of rotation of the bucket from zero.

The principle of operation of the centrifuge also can be simply understood in terms of this expression for the potential energy, which shows that it is favorable energetically when the volume far from the axis of rotation is occupied by the heavier substance.