Newton polygon

In mathematics, the Newton polygon is a tool for understanding the behaviour of polynomials over local fields, or more generally, over ultrametric fields.

In the original case, the ultrametric field of interest was essentially the field of formal Laurent series in the indeterminate X, i.e. the field of fractions of the formal power series ring

This is still of considerable utility with respect to Puiseux expansions.

The Newton polygon is an effective device for understanding the leading terms

of the power series expansion solutions to equations

, the polynomial ring; that is, implicitly defined algebraic functions.

here are certain rational numbers, depending on the branch chosen; and the solutions themselves are power series in

The Newton polygon gives an effective, algorithmic approach to calculating

After the introduction of the p-adic numbers, it was shown that the Newton polygon is just as useful in questions of ramification for local fields, and hence in algebraic number theory.

Newton polygons have also been useful in the study of elliptic curves.

Newton polygons provide one technique for the study of the behaviour of the roots.

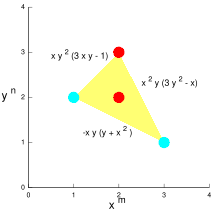

is defined to be the lower boundary of the convex hull of the set of points

Restated geometrically, plot all of these points Pi on the xy-plane.

Then, starting at P0, draw a ray straight down parallel with the y-axis, and rotate this ray counter-clockwise until it hits the point Pk1 (not necessarily P1).

Now draw a second ray from Pk1 straight down parallel with the y-axis, and rotate this ray counter-clockwise until it hits the point Pk2.

Continue until the process reaches the point Pn; the resulting polygon (containing the points P0, Pk1, Pk2, ..., Pkm, Pn) is the Newton polygon.

Another, perhaps more intuitive way to view this process is this : consider a rubber band surrounding all the points P0, ..., Pn.

Stretch the band upwards, such that the band is stuck on its lower side by some of the points (the points act like nails, partially hammered into the xy plane).

For a neat diagram of this see Ch6 §3 of "Local Fields" by JWS Cassels, LMS Student Texts 3, CUP 1986.

With the notations in the previous section, the main result concerning the Newton polygon is the following theorem,[1] which states that the valuation of the roots of

be the slopes of the line segments of the Newton polygon of

be the corresponding lengths of the line segments projected onto the x-axis (i.e. if we have a line segment stretching between the points

With the notation of the previous sections, we denote, in what follows, by

Another simple corollary is the following: Proof: By the main theorem,

More generally, the following factorization theorem holds: Proof: For every

Repeat the previous argument with the minimal polynomial of

The following is an immediate corollary of the factorization above, and constitutes a test for the reducibility of polynomials over Henselian fields: Other applications of the Newton polygon comes from the fact that a Newton Polygon is sometimes a special case of a Newton polytope, and can be used to construct asymptotic solutions of two-variable polynomial equations like

In the context of a valuation, we are given certain information in the form of the valuations of elementary symmetric functions of the roots of a polynomial, and require information on the valuations of the actual roots, in an algebraic closure.

The valid inferences possible are to the valuations of power sums, by means of Newton's identities.

Newton polygons are named after Isaac Newton, who first described them and some of their uses in correspondence from the year 1676 addressed to Henry Oldenburg.