Nicopolis

This foundation echoed a tradition dating back to Alexander the Great, and more recently illustrated by Pompey, founder of Nicopolis in Little Armenia (63 BC).

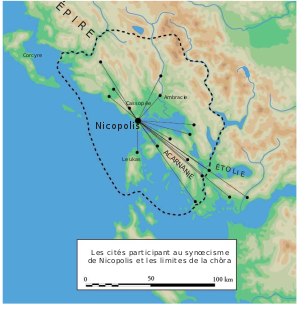

Many inhabitants of the surrounding areas – Kassopaia, Ambracia, parts of Acarnania (including Leukas, Palairos, Amphilochian Argos, Calydon, and Lysimachia) and western Aetolia – were forced to relocate to the new city.

Thus provided with considerable assets by its founder, the new city developed rapidly in Roman times; Augustus adorned it with monuments financed by the spoils of war, but it also owes much to the patronage of Herod the Great.

4), ensured the commercial development of the city which was built on the Roman orthogonal grid distinguished by its considerable size (about 180 ha).

Germanicus, nephew and adopted son of Augustus, visited the city en route to Syria and celebrated his second consulship there in 18 AD.

In 66, in the wake of a terror campaign and financial constraints in Rome, Emperor Nero made a more modest trip to Greece in lieu of a planned great journey to the east.

The new province included Acarnania to the south as far as the Achelous, but not Apollonia to the north, plus the Ionian Islands – Corfu, Leukas, Ithaca, Cephalonia, and Zacynthus.

The imperial couple were received with the highest honours: small altars in the city attest to the worship of Hadrian and Sabina, respectively assimilated to Zeus Dodonaios, the most important deity of Epirus, and Artemis Kelkaia, a manifestation of the goddess unknown outside Nicopolis.

The late third century was a time of troubles for the whole Empire: the city was attacked by the Goths and Heruli, but managed to avoid looting thanks to makeshift fortifications.

Here imperial land and sea forces counter-attacked, and the invaders wandered their way through Boeotia, Acarnania, Epirus, Macedonia, and Thrace on their way back to Moesia.

In about 330, the first great recorded Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea mentions that bishops from Epirus attended the first Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325.

In 361, newly appointed Consul and rhetorician Claudius Mamertinus delivered a panegyric to the young Emperor Julian (360–363), mentioning heavy taxation in Dalmatia and Epirus.

[9] Based on the record of Julian's close ties with certain leading men from Epirus involved in the Empire-wide cultural circuit led by Libanius and Themistius, it appears that Christianity was not widespread in Epirus in the mid-4th century (and as part of his pagan policy, Julian reactivated support of the Actian games), but after his death it spread far and wide in the region, judging from legislation issued by Valentinian in 371 and 372, trying to offset some negative effects of its rapid spread, and the fact that there is no written record of the bishops of the cities of Epirus until the 5th century, except for the bishop of Nicopolis in 343.

Diadochos’ texts also show us that both theoretical and practical ideas about theology and the organization of monastic life also spread from the eastern Mediterranean to Epirus.

In fact, a reference in one of Diadochos’ own writings suggests he was also the hegumen of a monastery in Photiki and that Epirus in the 450s at least had both anchoretic and coenobitic monastic communities.

But during the negotiations, in order to strengthen their position, the Vandals again devastated the coast of Greece during which they captured Nicopolis and took prisoners who had to be ransomed to secure their release.

This raid and prisoner-taking probably had a devastating effect on the infrastructure of Nicopolis and the mentality of its citizens, affecting the city's social and economic life.

It is probably directly related to the reduction of the city's population to one-sixth of what it had been, confining it to the north-east section, the area where the citadel stood, and fortifying it with thick walls to provide better defence.

Around 500, as mentioned, Bishop Alcison (491–516), an opponent of the Monophysite policy of Emperor Anastasius, supervised the addition of annexes to the five-aisled metropolitan basilica B, which has taken his name.

In 551, King Totila of the Ostrogoths, in response to reports of a Byzantine military build-up in the eastern side of the Adriatic, sent a 300-strong fleet to Corfu.

In 587, the Avars allied with Slavic tribes invaded Thrace, Macedonia and Achaua, including Thessaly, Attica, Euboia, and Peloponnesos, as well as Epirus Vetus, where the invasion seems to have reached as far as Euroea, but not Cassope and Nicopolis.

In 625, Pope Honorius I sent a letter to Metropolitan Hypatius of Nicopolis referring to the difficult travel conditions that prevented the bishop from reaching Rome.

Soon afterwards, owing to the decadence into which Nicopolis fell, the metropolitan see was transferred to Naupactus, which subsequently figured as such in the Notitiae episcopatuum.

In 1798 French Revolutionary troops, stationed in Preveza by Napoleon, dug into the graves and ruins of ancient Nicopolis and looted various treasures.