Nigel Williams (conservator)

After nearly 31,000 fragments of shattered Greek vases were found in 1974 amidst the wreck of HMS Colossus, Williams set to work piecing them together.

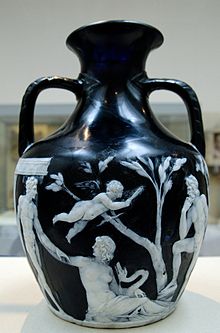

A decade later, in 1988 and 1989, Williams's crowning achievement came when he took to pieces the Portland Vase, one of the most famous glass objects in the world, and put it back together.

[4][5][6] Conservation was not a recognized profession at the time, and Williams became only the second member of the museum to study the field in a three-year part-time course at University College London's Institute of Archaeology.

[4] He conserved metals (including clocks and watches), glass, stone, ivory, wood, and various other organic materials,[4][5] yet more than anything he worked with ceramics, which became "the abiding passion of his life.

[4][10] Between these achievements Williams also pieced together the nearly 31,000 fragments of Greek vases found in the wreck of HMS Colossus (1787), and in 1983 was promoted to Chief Conservator of Ceramics and Glass, a position he held until his death.

[4] In 1968, as the re-excavation at Sutton Hoo reached its conclusion and with problems apparent in the reconstructions of several of the finds, Williams was put in charge of a team tasked with their continued conservation.

[4][15] Williams's colleagues at the museum termed the Sutton Hoo helmet his "pièce de résistance";[4][5] the iconic artefact from England's most famous archaeological discovery,[16] it had previously been restored in 1945–1946 by Herbert Maryon.

[25] A salvage operation following the wreck's 1974 discovery unearthed some 30,935 fragments,[26] and when they were acquired by the British Museum, Williams set to work reconstructing them.

[27] "He worked as if he were alone, and many people remember the moment in the resulting Chronicle programme when he uttered a four-letter word as one of his partially-completed restorations fell apart before the cameras.

[39] He deconstructed the vase by wrapping it inside and out with blotting paper and letting it sit in a glass desiccator injected with solvents for three days, leaving it in 189 pieces.

[4] These fears proved unfounded: a few more weeks spent working on the top half of the vase, and the final pieces joined perfectly.

[48] She likewise contributed to the Sutton Hoo finds, being employed by the British Museum to work on the remnants of the lyre and co-authoring a paper with her father.

[4][5] He had recently arrived[54] in Aqaba, Jordan,[4][5] and was taking a break on the beach from his work as the on-site conservator for a British Museum excavation at Tell es-Sa'idiyeh.