Nikita Pustosvyat. Debate about faith

[1] The painting depicts the dramatic moment of the "faith Debate" — a historical event of the Moscow Uprising of 1682, the bicentennial of which Perov planned to complete the work on canvas.

The writer Nikolai Leskov noted that "the painting Nikita Pustosvyat represents an amazing fact of artistic penetration"[5][6] and the critic Vladimir Stasov wrote that Perov had "not only a crowd, agitated, rebellious, rumbling with a storm, but also soloists, colossal singers".

[8] At the same time, Perov's role in creating the concept of a historical hero who was ready to give his life for his beliefs was recognized, and the historicism permeating the entire figurative structure of the canvas was noted.

[15] In an article on Perov included in volume 13 of the Russian Biographical Dictionary, the art historian Alexei Novitsky reports some information given to him by Elizaveta Egorovna,[16] the artist's widow.

According to her, the idea of creating the painting Nikita Pustosvyat most likely came to Perov under the influence of his communication with the writer Pavel Melnikov-Pechersky, with whom the artist repeatedly discussed problems of schism history.

The art historian Nikolai Sobko wrote that Perov was dissatisfied with many aspects of the painting, especially its right side, and "planned a lot of rewrites here anew, but death prevented him from fulfilling this intention".

In particular, the artist Vladimir Osipov (a student of Pavel Chistyakov) expressed the following opinion about this work by Perov: "What beautiful things of his youth, what conscientiousness of execution.

Tsarevna Sophia Alekseevna decided to take advantage of the discontent of the streltsy, who sided with Miloslavsky and executed a number of representatives of the Naryshkin family and their supporters.

Their representatives gathered in Moscow and preached their views on the streltsky regiments, as well as proposed to hold an open theological debate on Red Square.

Despite the support of Khovansky, the Old Believers failed to hold an open discussion, but on July 5, 1682, a "dispute about faith" took place in the Faceted Chamber of the Moscow Kremlin in the presence of Tsarevna Sophia Alekseevna and Patriarch Joachim.

Nikita Pustosvyat answered: "We have come to the tsar-sovereigns to ask them to correct the Orthodox faith, to give us their righteous consideration with you, the new lawmakers, and that the churches of God be in peace and harmony."

[30] Art historian Alla Vereshchagina wrote that "the composition is based on the opposition of the left and right parts of the painting: the dissenters and the official entourage of Sophia and the patriarch".

[4] Discussing the composition of the final version of the painting, art historian Alexei Fedorov-Davydov noted that the artist had arrived at "the academic method of arrangement of figures on an oval, somewhat open in front, with filling the corners of the canvas with secondary groups".

[35] Comparing this with Ilya Repin's painting Tsarevna Sophia Alexeevna a Year After Her Imprisonment in the Novodevichy Convent... (1879, State Tretyakov Gallery), art historian Nonna Yakovleva noted that Perov's image of Tsarevna Sophia is "a kind of antithesis to Repin's: she has the same strength of character, but noble; she is good-looking and bright even in anger," and "she stands above the battle, humbling it".

[36] Art historian Olga Lyaskovskaya wrote that Perov's female figures turned out to be the weakest, noting that perhaps he was planning to work further on the image of Sophia.

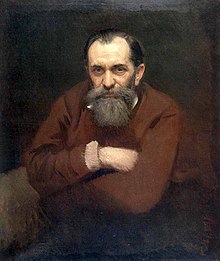

[37] On the part of the Old Believers, the protagonist is Nikita Pustosvyat, "a disheveled, tempestuous figure, with a sharp beard sticking forward," in whose image "sounds the theme of fanaticism, devotion to the idea of self-destruction".

[38] So it happened in reality: Sophia could not tolerate the existence of an opponent-preacher so fanatically devoted to his ideas and beliefs, and soon after the dispute about faith, Nikita Pustosvyat was captured by the Streltsy and beheaded.

[44] In 1887, comparing Surikov's Boyaryna Morozova with Perov's Nikita Pustosvyat, art critic Vladimir Stasov wrote that Perov had "not only one crowd, excited, rebellious, rumbling storm, but also soloists, colossal singers," which, in his opinion, primarily includes Nikita Pustosvyat himself — "turbulent, passionate, irritated, loudly and unbridledly reproaching everyone for apostasy," as well as standing a little behind him "his comrade, with a large icon in his hands, also a schismatic fanatic, but imperturbable and unshakable, like granite, like a rock, which will break all the seething waves of enemies and friends".

[45] At the same time, however, Stasov recognized that Perov poorly succeeded, in his view, in "multisyllabic" scenes, and that the entire left side of the picture "is already completely devoid of any talent, characterization, and truth".

[46] In Soviet times, historical works from Vasily Perov's late period were sharply criticized, and his views on history and religion were regarded as reactionary.

[47] Art historian Vladislav Zimenko generally also considered the painting Nikita Pustosvyat unsuccessful, nevertheless recognizing the expressiveness of a number of images presented in it.

Among these, he singled out the expressive figure of Nikita Pustosvyat — "a passionate, dry face with a sharp, sharply protruding forward beard angrily turned to the opponents of the 'true faith'."

[48] Art historian Vladimir Obukhov noted that, in working on the images of Nikita Pustosvyat and his comrades, Vasily Perov showed himself as one of the creators of the concept of the historical hero — "active, responsible for each of his actions, ready to give his own life for his beliefs".

Among other shortcomings, Obukhov mentioned the conspicuous rigidity of the painting, "some compositional discord," as well as the conventionality of the images of some characters — in particular, Tsarevna Sophia and Archbishop Athanasius.

[9] Discussing works on historical and religious themes created by Perov in the last decade of his life, art historian Vladimir Lenyashin noted that in general they were not properly appreciated in artistic circles.