Nikolay Nekrasov

"[7] In January 1823 Alexey Nekrasov, ranked army major, retired and moved the family to his estate in Greshnevo, Yaroslavl province, near the Volga River, where young Nikolai spent his childhood years with his five siblings, brothers Andrey (b.

[3] Things turned for the better when he started to give private lessons and contribute to the Literary Supplement to Russky Invalid, all the while compiling ABC-books and versified fairytales for children and vaudevilles, under the pseudonym Perepelsky.

"He might have easily become a brilliant general, outstanding scientist, rich merchant, should he have put his heart to it," argued Nikolai Mikhaylovsky, praising Nekrasov's stubbornness in pursuing his own way.

[6] In February 1840 Nekrasov published his first collection of poetry Dreams and Sounds, using initials "N. N." following the advice of his patron Vasily Zhukovsky who suggested the author might feel ashamed of his childish exercises in several years' time.

[11] The barrage of prose he published in the early 1840s was, admittedly, worthless, but several of his plays (notably, No Hiding a Needle in a Sack) were produced at the Alexandrinsky Theatre to some commercial success.

[11] Among the work of fiction written by Nekrasov in those years was his unfinished autobiographical novel The Life and Adventures of Tikhon Trostnikov (1843–1848); some of its motifs would be found later in his poetry ("The Unhappy Ones", 1856; On the Street, 1850, "The Cabman", 1855).

Much of the staff of the old Otechestvennye Zapiski, including Belinsky, abandoned Andrey Krayevsky's magazine, and joined Sovremennik to work with Nekrasov, Panayev and Alexander Nikitenko, a nominal editor-in-chief.

[11] In order to fill up the gaps caused by censorial interference he started to produce lengthy picturesque novels (Three Countries of the World, 1848–1849, The Dead Lake, 1851), co-authored by Avdotya Panayeva, his common-law wife.

Gambling (a habit shared by male ancestors on his father's side; his grandfather lost most of the family estate through it) was put to the service too, and as a member of the English Club Nekrasov made a lot of useful acquaintances.

[11] In the end of 1866 Nekrasov purchased Otechestvennye Zapiski to become this publication's editor with Grigory Yeliseyev as his deputy (soon joined by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin) and previous owner Krayevsky as an administrator.

The 20-year-old Nekrasov fell in love but had to wait several years for her emotional response and at least on one occasion was on the verge of suicide, if one of his Panayeva Cycle poems, "Some time ago, rejected by you... " is to be believed.

A bizarre romantic/professional team which united colleagues and lovers (she continued 'dating' her husband, sending her jealous lodger into fits of fury) was difficult for both men, doubly so for a woman in a society foreign to such experiments.

Dismissed by many critics as little more than a ploy serving to fill the gaps in Sovremennik left by censorial cuts and criticised by some of the colleagues (Vasily Botkin regarded such a manufacture as 'humiliating for literature'), in retrospect they are seen as uneven but curious literary experiments not without their artistic merits.

According to Panayev, the autobiographical "Motherland" (Родина, 1846), banned by censors and published ten years later, "drove Belinsky totally crazy, he learnt it by heart and sent it to his Moscow friends".

[12][30] "When from the darkness of delusion..." (Когда из мрака заблужденья..., 1845), arguably the first poem in Russia about the plight of a woman driven to prostitution by poverty, brought Chernyshevsky to tears.

[4] "The most melodious of Nekrasov's poems is Korobeiniki, the story which, although tragic, is told in the life-affirming, optimistic tone, and yet features another, strong and powerful even if bizarre motif, that of 'The Wanderer's Song'," wrote Mirsky.

[7] Among Nekrasov's best known poems of the early 1860 were "Peasant Children" (Крестьянские дети, 1861), highlighting moral values of the Russian peasantry, and "A Knight for an Hour" (Рыцарь на час, 1862), written after the author's visit to his mother's grave.

Full of humour and great sympathy for the peasant youth, "Grandfather Mazay and the Hares" (Дедушка Мазай и зайцы) and "General Stomping-Bear" (Генерал Топтыгин) up to this day remain the children's favourites in his country.

[4][11] In the 1870s the general tone of Nekrasov's poetry changed: it became more declarative, over-dramatized and featured the recurring image of poet as a priest, serving "the throne of truth, love and beauty."

[4] In the 1850s and 1860s, Nekrasov (backed by two of his younger friends and allies, Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov) became the leader of a politicized, social justice-oriented trend in Russian poetry (evolved from the Gogol-founded natural school in prose) and exerted a strong influence upon the young radical intelligentsia.

[39] In 1860 the so-called 'Nekrasov school' in Russian poetry started to take shape, uniting realist poets like Dmitry Minayev, Nikolai Dobrolyubov, Ivan Nikitin and Vasily Kurochkin, among others.

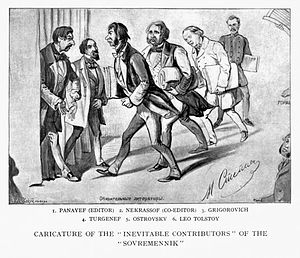

During its 20 years of steady and careful literary policy, Sovremennik served as a cultural forum for all the major Russian writers, including Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev, and Leo Tolstoy, as well as Nekrasov's own poetry and prose.

[49] Georgy Plekhanov who in his 1902 article glorified 'Nekrasov the Revolutionary' insisted that "one is obliged to read him... in spite of occasional faults of the form" and his "inadequacy in terms of the demands of esthetic taste.

"[50] According to one school of thought (formulated among others by Vasily Rosanov in his 1916 essay), Nekrasov in the context of the Russian history of literature was an "alien... who came from nowhere" and grew into a destructive 'anti-Pushkin' force to crash with his powerful, yet artless verse the tradition of "shining harmonies" set by the classic.

Mixing social awareness and political rhetoric with such conservative subgenres as elegy, traditional romance and romantic ballad, he opened new ways, particularly for the Russian Modernists some of whom (Zinaida Gippius, Valery Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Alexander Blok) professed admiration for the poet, citing him as an influence.

Never does the poet indulge himself with his usual moaning and conducts the narrative in the tone of sharp but good-natured satire very much in the vein of a common peasant talk... Full of extraordinary verbal expressiveness, energy and many discoveries, it's one of the most original Russian poems of the 19th century.

Nekrasov's dramatic method implied the narrator's total closeness to his hero whom he 'played out' as an actor, revealing motives, employing sarcasm rather than wrath, either ironically eulogizing villains ("Musings by the Front Door"), or providing the objects of his satires a tribune for long, self-exposing monologues ("A Moral Man", "Fragments of the Travel Sketches by Count Garansky", "The Railroad").

[55] Several of his lines (like "Seyat razumnoye, dobroye, vetchnoye..." – "To saw the seeds of all things sensible, kind, eternal..." or "Suzhdeny vam blagiye poryvi/ No svershit nichevo ne dano".

After Nekrasov's death his poetry continued to be judged along the party lines, rejected en bloc by the right wing and praised in spite of its inadequate form by the left.

Nekrasov's estate in Karabikha, his St. Petersburg home, as well as the office of Sovremennik magazine on Liteyny Prospekt, are now national cultural landmarks and public museums of Russian literature.

Illustration by Boris Kustodiev

Nekrasov, as a real innovator in Russian literature, was closely linked to the tradition set by his great predecessors, first and foremost, Pushkin. – Korney Chukovsky , 1952 [ 40 ]

Nekrasov was totally devoid of memory, unaware of any tradition and foreign to the notion of historical gratitude. He came from nowhere and drew his own line, starting with himself, never much caring for anybody else. – Vasily Rozanov , 1916 [ 41 ]