Nikolay Bobrikov

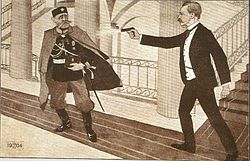

After appointment as the governor-general, he quickly became very unpopular and was assassinated by Eugen Schauman, a Finnish nationalist born in Kharkiv.

Nikolay Ivanovich Bobrikov was born on January 15, 1839 in the village of Strelna near Saint Petersburg and attended the 1st Cadet Corps.

After Olga's death in 1895 Bobrikov was married again to Elizabeth (Yelizaveta Ivanovna) Staël von Holstein, the daughter of a general.

One of Bobrikov's sons-in-law was the Norwegian-born Finnish officer Johannes Holmsen, who was later promoted to lieutenant general.

In the early days of World War I, Holmsen was captured by the Germans but later got to live in Norway, where he died after the Russian Revolution.

[4]: 67, 69 in 1889, Emperor Alexander II of Russia appointed Bobrikov as a member of the special committee (Verhovnaya Rasporyaditelnaya Komissiya) led by Mikhail Loris-Melikov.

Upon appointment, he introduced a Russification programme into the Grand Duchy, the 11 main points were: Bobrikov quickly became very unpopular and hated in Finland as he was an adamant supporter of the curtailing of the grand duchy's extensive autonomy, which had in the late 1800s come into conflict with Russian ambitions of a unified and indivisible Russian state.

In 1899, Nicholas II signed the "February Manifesto" which marked the beginning of the first "Years of Oppression" (sortovuodet) from the traditional Finnish perspective.

In this manifesto the tsar decreed that the Diet of the Estates of Finland could be overruled in legislation if it was in Russian imperial interest.

Half a million Finns, considering the decree a coup against the Finnish constitution, signed a petition to Nicholas II, requesting to revoke the manifesto.

Journalist Valfrid Spångberg of the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet visited Bobrikov on 1 March 1899 to ask a few questions about the February Manifesto.

The internal order in Finland is excellent, and the Finns are a lawful and patriotic people, which I greatly respect, as I do the Senate and the Estates.

I am a friend of the press, but the Finnish newspapers are accustomed to a way of speaking that I cannot accept, and they present views which I feel cannot do anything else than spread discomfort and cause damage.

[12]: 21 [13]: 182–182 About 1000 to 2000 "laukkuryssäs" ("bag Russians"), meaning peddlers from White Karelia, circulated the country, spreading rumours of how excellently Russia had handled things for the landless people and for the farmers.

To combat this, the labour movement, youth societies and students such as Eugen Schauman started educating people about what the circumstances in Russia were really like.

[8]: 246–252 [13]: 182–187 [2]: 276 [9]: 464 The Porvoo-based newspaper Uusimaa claimed that the rumours had originated from the Moskovskiye Vedomosti secret Finnish correspondent P. I. Messarosch.

[8]: 255 According to Senator Gripenberg, the agitation done by the Russian peddlers was an act of purposeful spreading of distrust between the different social classes in Finland.

By Bobrikov's initiative, a law was passed on 2 July 1900 making the Russian peddler trade legal.