Halo (religious iconography)

A halo (from Ancient Greek ἅλως, hálōs, 'threshing floor, disk'),[1][2] also called a nimbus, aureole, glory or gloriole (Latin: gloriola, lit.

"[5] Persian mythology, and later Zoroastrian philosophy, speaks of the similar concept of Khvarenah (later farrah), a divine, radiant power that sanctified a king and his reign.

[6] Depictions of Perseus in the act of slaying Medusa, with lines radiating from his head, appear on a white-ground toiletry box and on a slightly later red-figured vase in the style of Polygnotos, c. 450–30 BC.

[7] On painted wares from south Italy, radiant lines or simple haloes appear on a range of mythic figures: Lyssa, a personification of madness; a sphinx; a sea demon; and Thetis, the sea-nymph who was mother to Achilles.

The rulers of the Kushan Empire were perhaps the earliest to give themselves haloes on their coins, and the nimbus in art may have originated in Central Asia and spread both east and west.

Tibetan Buddhism uses haloes and aureoles of many types, drawing from both Indian and Chinese traditions, extensively in statues and Thangka paintings of Buddhist saints such as Milarepa and Padmasambhava and deities.

[14] Elaborate haloes and especially aureoles also appear in Hindu sculpture, where they tend to develop into architectural frames in which the original idea can be hard to recognise.

[20] The Ottomans avoided using halos for the sultans, despite their title as Caliph, and they are only seen on Chinese emperors if they are posing as Buddhist religious figures, as some felt entitled to do.

It first appeared in the culture of Hellenistic Greece and Rome, possibly related to the Zoroastrian hvarena – "glory" or "divine lustre" – which marked the Persian kings, and may have been imported with Mithraism.

In a late 2nd century AD floor mosaic from Thysdrus, El Djem, (illustration) Apollo Helios is identified by his effulgent halo.

[25] The conventions of this representation, head tilted, lips slightly parted, large-eyed, curling hair cut in locks grazing the neck, were developed in the 3rd century BC to depict Alexander the Great (Bieber 1964; Yalouris 1980).

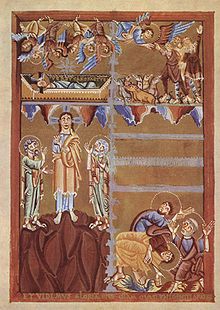

[27] The halo was incorporated into Early Christian art sometime in the 4th century with the earliest iconic images of Christ, initially the only figure shown with one (together with his symbol, the Lamb of God).

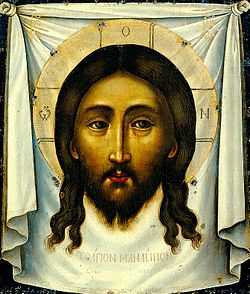

Plain round haloes are typically used to signify saints, the Virgin Mary, Old Testament prophets, angels, symbols of the Four Evangelists, and some other figures.

[34] Mary has, especially from the Baroque period onwards, a special form of halo in a circle of twelve stars, derived from her identification as the Woman of the Apocalypse.

The whole-body image of radiance is sometimes called the 'aureole' or glory; it is shown radiating from all round the body, most often of Christ or Mary, occasionally of saints (especially those reported to have been seen surrounded by one).

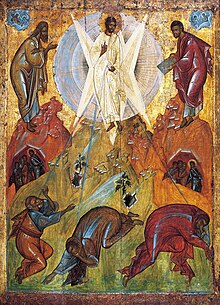

In depictions of the Transfiguration of Jesus a more complicated shape is often seen, especially in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, as in the famous 15th century icon in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

The gold leaf inside the halo may also be burnished in a circular manner, so as to produce the effect of light radiating out from the subject's head.

Generally they lasted longer in Italy, although often reduced to a thin gold band depicting the outer edge of the nimbus, usual for example in Giovanni Bellini.

Fra Angelico, himself a monk, was a conservative as far as haloes are concerned, and some of his paintings demonstrate the problems well, as in several of his more crowded compositions, where they are shown as solid gold disks on the same plane as the picture surface, it becomes difficult to prevent them obstructing other figures.

[45] In the High Renaissance, even most Italian painters dispensed with haloes altogether, but in the Church's reaction to the Protestant Reformation, that culminated in the decrees on images of the Council of Trent of 1563, their use was mandated by clerical writers on religious art such as Molanus and Saint Carlo Borromeo.

[46] In popular graphic culture, a simple ring has become the predominant representation of a halo since at least the late 19th century, as seen for example in the logo for the Simon Templar ("The Saint") series of novels and other adaptations.

[47] Halo comes originally from the Greek for "threshing-floor" – a circular, slightly sloping area kept very clean, around which slaves or oxen walked to thresh the grain.

[48] Aureole, from the Latin for "golden", has been used in English as a term for a gold crown, especially that traditionally considered the reward of martyrs, since the Middle Ages (OED 1220).

[53] A more Catholic interpretation is that the halo represents the light of divine grace suffusing the soul, which is perfectly united and in harmony with the physical body.