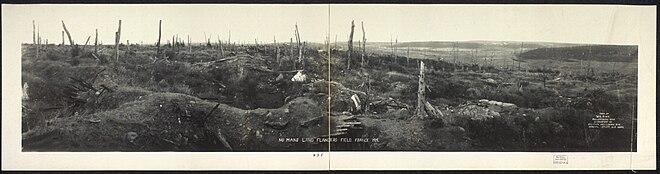

No man's land

[7][8] The Oxford English Dictionary contains a reference to the term dating back to 1320, spelled nonesmanneslond, to describe a territory that was disputed or involved in a legal disagreement.

[9] The term is also applied in nautical use to a space amidships, originally between the forecastle and the booms in a square-rigged vessel where various ropes, tackle, block, and other supplies were stored.

[11] The Anglo-German Christmas truce of 1914 brought the term into common use, and thereafter it appeared frequently in official communiqués, newspaper reports, and personnel correspondences of the members of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

[12] Heavily defended by machine guns, mortars, artillery, and riflemen on both sides, it was often extensively cratered by exploded shells, riddled with barbed wire, and littered with rudimentary land mines; as well as the corpses and wounded soldiers who were unable to make it through the hailstorm of projectiles, explosions, and flames.

[13] Not only were soldiers forced to cross no man's land when advancing, and as the case might be when retreating, but after an attack the stretcher-bearers had to enter it to bring in the wounded.

[14] No man's land remained a regular feature of the battlefield until near the end of World War I when mechanised weapons (i.e., tanks and airplanes) made entrenched lines less of an obstacle.

The zone is sealed off completely and still deemed too dangerous for civilians to return: "The area is still considered to be very poisoned, so the French government planted an enormous forest of black pines, like a living sarcophagus", comments Alasdair Pinkerton, a researcher at Royal Holloway University of London, who compared the zone to the nuclear disaster site at Chernobyl, similarly encased in a "concrete sarcophagus".

Officially the territory belonged to the Eastern Bloc countries, but over the entire Iron Curtain, there were several wide tracts of uninhabited land, several hundred meters (yards) in width, containing watch towers, minefields, unexploded bombs, and other such debris.

[26] On 11 January 2023, Ukrainian presidential adviser Mykhailo Podolyak described the fighting ongoing at Bakhmut and Soledar as the bloodiest since the start of the invasion.