Nobelium

A radioactive metal, it is the tenth transuranium element, the second transfermium, and is the penultimate member of the actinide series.

[18] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

[k] The discovery of element 102 was a complicated process and was claimed by groups from Sweden, the United States, and the Soviet Union.

The first complete and incontrovertible report of its detection only came in 1966 from the Joint Institute of Nuclear Research at Dubna (then in the Soviet Union).

Twelve out of the fifty bombardments contained samples emitting (8.5 ± 0.1) MeV alpha particles, which were in drops which eluted earlier than fermium (atomic number Z = 100) and californium (Z = 98).

The half-life reported was 10 minutes and was assigned to either 251102 or 253102, although the possibility that the alpha particles observed were from a presumably short-lived mendelevium (Z = 101) isotope created from the electron capture of element 102 was not excluded.

[50] The team proposed the name nobelium (No) for the new element,[51][52] which was immediately approved by IUPAC,[53] a decision which the Dubna group characterized in 1968 as being hasty.

The Berkeley team, consisting of Albert Ghiorso, Glenn T. Seaborg, John R. Walton and Torbjørn Sikkeland, used the new heavy-ion linear accelerator (HILAC) to bombard a curium target (95% 244Cm and 5% 246Cm) with 13C and 12C ions.

However, later work has shown that no nobelium isotopes lighter than 259No (no heavier isotopes could have been produced in the Swedish experiments) with a half-life over 3 minutes exist, and that the Swedish team's results are most likely from thorium-225, which has a half-life of 8 minutes and quickly undergoes triple alpha decay to polonium-213, which has a decay energy of 8.53612 MeV.

[53] In 1959, the team continued their studies and claimed that they were able to produce an isotope that decayed predominantly by emission of an 8.3 MeV alpha particle, with a half-life of 3 s with an associated 30% spontaneous fission branch.

Some alpha decays with energies just over 8.5 MeV were observed, and they were assigned to 251,252,253102, although the team wrote that formation of isotopes from lead or bismuth impurities (which would not produce nobelium) could not be ruled out.

[50] One more very convincing experiment from Dubna was published in 1966 (though it was submitted in 1965), again using the same two reactions, which concluded that 254102 indeed had a half-life much longer than the 3 seconds claimed by Berkeley.

[50] Later work in 1967 at Berkeley and 1971 at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory fully confirmed the discovery of element 102 and clarified earlier observations.

[53] In December 1966, the Berkeley group repeated the Dubna experiments and fully confirmed them, and used this data to finally assign correctly the isotopes they had previously synthesized but could not yet identify at the time, and thus claimed to have discovered nobelium in 1958 to 1961.

[53] In 1969, the Dubna team carried out chemical experiments on element 102 and concluded that it behaved as the heavier homologue of ytterbium.

For element 102, it ratified the name nobelium (No) on the basis that it had become entrenched in the literature over the course of 30 years and that Alfred Nobel should be commemorated in this fashion.

[60] Like the other divalent late actinides (except the once again trivalent lawrencium), metallic nobelium should assume a face-centered cubic crystal structure.

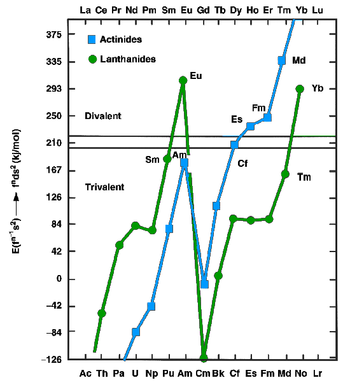

[51] It was largely expected before the discovery of nobelium that in solution, it would behave like the other actinides, with the trivalent state being predominant; however, Seaborg predicted in 1949 that the +2 state would also be relatively stable for nobelium, as the No2+ ion would have the ground-state electron configuration [Rn]5f14, including the stable filled 5f14 shell.

[65] Determination of nobelium's favoring of the +2 state had to wait until the next year, when cation-exchange chromatography and coprecipitation experiments were carried out on around fifty thousand 255No atoms, finding that it behaved differently from the other actinides and more like the divalent alkaline earth metals.

In this molecule, nobelium is expected to exhibit main-group-like behavior, specifically acting like an alkaline earth metal with its ns2 valence shell configuration and core-like 5f orbitals.

[65] The standard reduction potential of the E°(No3+→No2+) couple was estimated in 1967 to be between +1.4 and +1.5 V;[65] it was later found in 2009 to be only about +0.75 V.[68] The positive value shows that No2+ is more stable than No3+ and that No3+ is a good oxidizing agent.

[6] Additionally, the shorter-lived 255No (half-life 3.1 minutes) is more often used in chemical experimentation because it can be produced in larger quantities from irradiation of californium-249 with carbon-12 ions.

However, a dip appears at 254No, and beyond this the half-lives of even-even nobelium isotopes drop sharply as spontaneous fission becomes the dominant decay mode.

[73][71][72] This shows that at nobelium, the mutual repulsion of protons poses a limit to the region of long-lived nuclei in the actinide series.

[75] The even-odd nobelium isotopes mostly continue to have longer half-lives as their mass numbers increase, with a dip in the trend at 257No.

Irradiating a 350 μg cm−2 target of californium-249 with three trillion (3 × 1012) 73 MeV carbon-12 ions per second for ten minutes can produce around 1200 nobelium-255 atoms.

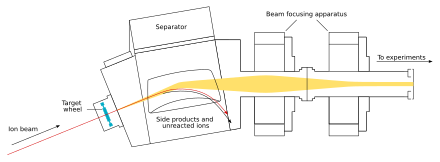

The recoil momentum of the produced nobelium-255 atoms is used to bring them physically far away from the target from which they are produced, bringing them onto a thin foil of metal (usually beryllium, aluminium, platinum, or gold) just behind the target in a vacuum: this is usually combined by trapping the nobelium atoms in a gas atmosphere (frequently helium), and carrying them along with a gas jet from a small opening in the reaction chamber.

Using a long capillary tube, and including potassium chloride aerosols in the helium gas, the nobelium atoms can be transported over tens of meters.

[76] The nobelium can then be isolated by exploiting its tendency to form the divalent state, unlike the other trivalent actinides: under typically used elution conditions (bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid (HDEHP) as stationary organic phase and 0.05 M hydrochloric acid as mobile aqueous phase, or using 3 M hydrochloric acid as an eluant from cation-exchange resin columns), nobelium will pass through the column and elute while the other trivalent actinides remain on the column.