Noël Doiron

For his "noble resignation" and self-sacrifice aboard the Duke William, Doiron was celebrated in popular print throughout the 19th century in England and America.

Noel Doiron was born at Port Royal, Acadia, but he lived most of his childhood at Pisiquid in the Parish of St. Famille (present-day Falmouth, Nova Scotia).

Some were held for ransom or exchange, and others, usually young women and children, were adopted into local Mohawk families to replace members who had died.

[4] While forcibly removed from their homes, Doiron, Marie and the other Acadian hostages were initially permitted to roam freely in the streets of Boston, much to the dismay of New Englanders.

During that time he and his family built dykes that still exist in the community, as well as a chapel at Burntcoat Head, Nova Scotia (formerly known as Steeple Point).

As with most Acadians in the Cobequid region, Doiron was likely a cattle farmer involved in supporting trade with the French Fortress of Louisbourg.

[citation needed] Early in Father Le Loutre's War, the British established Halifax in 1749 and built fortifications in all the major Acadian communities.

In response to the war and the British taking control over Acadia, the inhabitants of the parish sent a request for assistance to Acadians residing in Beaubassin.

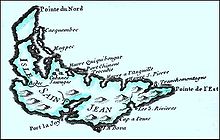

"Early in 1750, Doiron and his family joined the Acadian Exodus and left mainland Nova Scotia for Pointe Prime, Ile St. Jean (present day Eldon, Prince Edward Island).

The census of 1752 reported: "the greater number amongst them had not even bread to eat ... [many] subsisted on the shell fish they gathered on the shores of the harbour when the tide was out.

"[citation needed] Food shortages were exacerbated when the French government ordered Acadians to cease fishing and focus exclusively on crop production—crops were required for troops at Louisbourg.

He resumed his priestly duties until he was "rescued" by forces loyal to the French Crown and transported to Point Prime on Ile St. Jean.

In a letter dated August 24, 1753, Girard wrote of the plight of the Pointe Prime Acadians: Our refugees ... this winter will not be in any condition to work, they lack tools, they cannot find shelter from the rigor of the cold by day or night.

The British authorities had given up on their earlier attempts to assimilate the Acadians into the American colonies and now wanted them returned directly to France.

The next day, those aboard the Duke William witnessed the sinking of the transport vessel Violet and the loss of 300 other Acadians who were on board.

It was stated in one report, that upon seeing the approaching vessels, Noel Doiron gripped the Captain "in his aged arms and cried for joy."

Captain Nichols later recorded that during the departure Doiron reprimanded a fellow Acadian for trying to board a lifeboat while abandoning his wife and children.

Doiron's priest Girard wrote that he "laid off the ship about half an hour, when their cries, and waving us to be gone, almost broke our hearts."