Nomination of Mayors under the French Third Republic

In a tentative reversal of the authoritarian Empire [fr]'s legislation, the local electoral law of June 1865 indicated that mayors should be appointed within the elected municipal council.

[5][3] In the aftermath of the Battle of Sedan, the restoration of the French Republic on September 4, 1870, witnessed the ascendance of a government comprising Republican parliamentarians, spearheaded by Jules Favre, who were staunch proponents of the universal suffrage espoused in the 1848 Revolution.

Consequently, from the inception of the Government of National Defense, the organization of elections commenced, as it was believed that this would prove to be the most efficacious method for restoring civil harmony domestically and peace externally.

[11] To resume the preparation of municipal elections, which had been interrupted by the Government of National Defense, Interior Minister Ernest Picard submitted a draft law on their organization to the Assembly on March 23, 1871.

[12] However, between September 1870 and March 1871, there had been a profound shift in the political balance of power, with the election of a majority of monarchist parliamentarians and the appointment of conservative Republican [fr] Adolphe Thiers as president of the Republic.

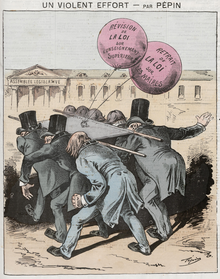

Nevertheless, an unanticipated coalition from the center to the left voted in favor of the amendment proposed by Agénor Bardoux, Amédée Lefèvre-Pontalis [fr], and Amable Ricard.

However, the parliamentary commission did not concede defeat, and Auguste Paris [fr] submitted an additional provision on its behalf, temporarily appointing mayors and deputies in all departmental and arrondissement capitals and all communes with more than 20,000 inhabitants.

Consequently, when Thiers addressed the Assembly on April 8, 1871, he made specific reference to the assault led by General La Villesboisnet [fr] against the insurgents of the Marseille Commune three days earlier:[18] Certainly, when in a city like Marseille, which is a very well-lit city—no one disputes that—it is a very wealthy city, having, therefore, a great interest in maintaining order, it is necessary to bring down five hundred sailors from their ships to restore the compromised order; when it is necessary to storm the prefecture... and do you know how?

This was observed by Anatole de Melun [fr] on March 26, 1873, a date that preceded the overthrow of Thiers by a mere few days: "The current of opinions changes quickly.

"[25] His superior, Albert de Broglie, explained: "I am convinced it is impossible to leave ministers, prefects, and sub-prefects responsible for enforcing laws when they cannot freely choose or dismiss the agents they are forced to use.

"[26] This conflict illustrated the ambiguity introduced since the French Revolution by combining mayors' municipal prerogatives and functions delegated by the central administration to communes, making them de facto "agents of the government.

Among the dissenters was the Marquis de Franclieu, who had submitted a preliminary question on January 8, 1874, requesting that the debate be postponed until the organic municipal law was discussed.

[26][29]On January 22, 1874, Baragnon distributed a circular from the Broglie cabinet requesting that prefects utilize revocation against mayors who opposed the Moral Order policy.

The selections made by municipal councils, influenced by partisan considerations, have frequently resulted in individuals who, due to their incompetence, background, or personal shortcomings, have undermined the integrity of the positions they have assumed.

For example, the Republican mayor of Selles-Saint-Denis was dismissed from his post after he permitted "scenes of public immorality" to occur in the drinking establishment that he owned and operated through his deputy.

For instance, when the municipality of Liniez declined to approve the requisite budget for repairing the rectory and church in February 1874, despite its authority to do so, the Minister of the Interior opted to register the expense instead of immediately dissolving the council as demanded by the sub-prefect of Issoudun.

[32] In the National Assembly, Deputy Mayor Jean-Baptiste Godin, who had been removed from office for promoting the socialist phalanstery system in his commune of Guise, directly opposed the conservatives by refusing to relinquish his functions until a replacement was found.

This resulted in a situation where Gambetta could express satisfaction, noting that "there are communes that today will not conduct a single municipal council election without first inquiring about each candidate's political opinions.

"[30][35] In the 1876 legislative election campaign, the moderate Republican daily newspaper Le Temps expressed concern that right-wing mayors might use their local influence to affect district ballots.

The Louis Buffet government [fr], "divided between the center-left and center-right", declined to yield to the pressures from either side and did not utilize the law to a significant extent in influencing the legislative elections.

Consequently, Demaine prevailed over Léon Gambetta in the Avignon arrondissement, whereas Delbreil was unsuccessful in his bid to enter the Chamber of Deputies [fr].

[37] The second Interior Minister of the Dufaure cabinet [fr], Émile de Marcère — a figure of the center-left —, in consideration of the primary objective being the dismissal of Broglie's mayors, declared himself to be aligned with the principle of complete appointment and opposed Léon Gambetta and Jules Ferry.

[41] Bardi de Fourtou sought to leverage the opportunities presented by the 1876 law to diminish the local influence of the Republicans and facilitate electoral maneuvers by the conservatives.

In the aftermath of the left's ascendance to executive authority, the prefects, invoking the 1876 law, allocated the affected mayoral positions to prominent Republican figures within the departments, frequently prioritizing an integration with parliamentary responsibilities.

[40] Léon Gambetta excluded the mayoral appointment reform from his "grand ministry" [fr] program, declaring his attachment to "French centralization, which corresponds to the history and spirit of unity of France" and expressing concern about the potential dangers of "these [liberal] theories in a country whose Revolution cemented all parts to make it stronger.

[45] To illustrate, in May 1886, the monarchist mayor of Barbentane, Pierre Terray [fr], was removed from office by presidential decree due to a brawl between Republicans and royalists during a communal festival.

[38] In the context of the outbreak of the Second World War and as a consequence of the signing of the German-Soviet Pact, the Daladier cabinet [fr] adopted the decree of September 26, 1939, which resulted in the removal of the 27 communist municipal councils in the Paris region.

The purge was completed by the law of January 20, 1940, which provided for the dismissal "of any member of an elected assembly who was part of the French Section of the Communist International" after October 26, 1940.

This ordinance declared the nullity of Petainist laws in this regard, canceled the designations made in Corsica, and established special delegations appointed by the London Government until it was possible to organize elections.