Nonmetal

Nonmetallic chemical elements are often described as lacking properties common to metals, namely shininess, pliability, good thermal and electrical conductivity, and a general capacity to form basic oxides.

[16][d] The shininess of boron, graphite (carbon), silicon, black phosphorus, germanium, arsenic, selenium, antimony, tellurium, and iodine[e] is a result of varying degrees of metallic conduction where the electrons can reflect incoming visible light.

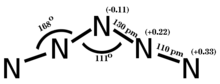

[43] For example, nitrogen forms diatomic molecules featuring a triple bonds between each atom, both of which thereby attain the configuration of the noble gas neon.

[48] Some do deform such as white phosphorus (soft as wax, pliable and can be cut with a knife, at room temperature),[49] in plastic sulfur,[50] and in selenium which can be drawn into wires from its molten state.

This behavior is related to the stability of electron configurations in the noble gases, which have complete outer shells as summarized by the duet and octet rules of thumb, more correctly explained in terms of valence bond theory.

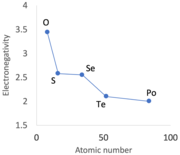

[68] For example, the chemically very active nonmetals fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine have an average electronegativity of 3.19—a figure[i] higher than that of any metallic element.

[73] The first 10 places in a "top 20" table of elements most frequently encountered in 895,501,834 compounds, as listed in the Chemical Abstracts Service register for November 2, 2021, were occupied by nonmetals.

It most commonly forms covalent bonds, but it can also lose its single electron in an aqueous solution, leaving behind a bare proton with tremendous polarizing power.

[80] Consequently, this proton can attach itself to the lone electron pair of an oxygen atom in a water molecule, laying the foundation for acid-base chemistry.

Such bonding, "helps give snowflakes their hexagonal symmetry, binds DNA into a double helix; shapes the three-dimensional forms of proteins; and even raises water's boiling point high enough to make a decent cup of tea.

[l] Higher oxidation states in later groups emerge from period 3 onwards, as seen in sulfur hexafluoride SF6, iodine heptafluoride IF7, and xenon(VIII) tetroxide XeO4.

Writing early in the twentieth century, by which time the era of modern chemistry had been well-established,[91] Humphrey[92] observed that: Examples of metal-like properties occurring in nonmetallic elements include: Examples of nonmetal-like properties occurring in metals are: A relatively recent development involves certain compounds of heavier p-block elements, such as silicon, phosphorus, germanium, arsenic and antimony, exhibiting behaviors typically associated with transition metal complexes.

This is linked to a small energy gap between their filled and empty molecular orbitals, which are the regions in a molecule where electrons reside and where they can be available for chemical reactions.

[128][v] Metalloids resemble the elements universally considered "nonmetals" in having relatively low densities, high electronegativity, and similar chemical behavior.

Due to their closed outer electron shells, noble gases possess weak interatomic forces of attraction, leading to exceptionally low melting and boiling points.

[132] While the halogen nonmetals are notably reactive and corrosive elements, they can also be found in everyday compounds like toothpaste (NaF); common table salt (NaCl); swimming pool disinfectant (NaBr); and food supplements (KI).

[133] Chemically, the halogen nonmetals exhibit high ionization energies, electron affinities, and electronegativity values, and are mostly relatively strong oxidizing agents.

[154] Very different, when combined with metals, the unclassified nonmetals can form interstitial or refractory compounds[155] due to their relatively small atomic radii and sufficiently low ionization energies.

A possible explanation comes from theoretical models of the high pressures in the Earth's core suggest there may be around 1013 tons of xenon, in the form of stable XeFe3 and XeNi3 intermetallic compounds.

[163] Five nonmetals—hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and silicon—form the bulk of the directly observable structure of the Earth: about 73% of the crust, 93% of the biomass, 96% of the hydrosphere, and over 99% of the atmosphere, as shown in the accompanying table.

[182] Around 340 BCE, in Book III of his treatise Meteorology, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle categorized substances found within the Earth into metals and "fossiles".

In his 1566 medical treatise, French physician Loys de L'Aunay distinguished substances from plant sources based on whether they originated from metallic or non-metallic soils.

[187] Later, the French chemist Nicolas Lémery discussed metallic and nonmetallic minerals in his work Universal Treatise on Simple Drugs, Arranged Alphabetically published in 1699.

French chemist Antoine Lavoisier published the first modern list of chemical elements in his revolutionary[190] 1789 Traité élémentaire de chimie.

[192] Lavoisier's work gained widespread recognition and was republished in twenty-three editions across six languages within its first seventeen years, significantly advancing the understanding of chemistry in Europe and America.

[194] However, in 1811, the Swedish chemist Berzelius used the term "metalloids"[195] to describe all nonmetallic elements, noting their ability to form negatively charged ions with oxygen in aqueous solutions.

[212] In 1828 and 1859, the French chemist Dumas classified nonmetals as (1) hydrogen; (2) fluorine to iodine; (3) oxygen to sulfur; (4) nitrogen to arsenic; and (5) carbon, boron and silicon,[213] thereby anticipating the vertical groupings of Mendeleev's 1871 periodic table.

Emsley[240] pointed out the complexity of this task, asserting that no single property alone can unequivocally assign elements to either the metal or nonmetal category.

[244] Similarly, despite its common classification as a nonmetallic element, carbon (as graphite) is a semimetal which when heated experiences a decrease in electrical conductivity.

The dashed lines around the columns for metalloids signify that the treatment of these elements as a distinct type can vary depending on the author, or classification scheme in use.