History of the periodic table

The history of the periodic table reflects over two centuries of growth in the understanding of the chemical and physical properties of the elements, with major contributions made by Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, John Newlands, Julius Lothar Meyer, Dmitri Mendeleev, Glenn T. Seaborg, and others.

Similar ideas existed in other ancient traditions, such as Indian philosophy with five elements: Earth, water, fire, air and aether collectively called 'pañca bhūta'.

[3] Of the chemical elements shown on the periodic table, nine – carbon, sulfur, iron, copper, silver, tin, gold, mercury, and lead – have been known since antiquity, as they are found in their native form and are relatively simple to mine with primitive tools.

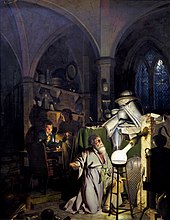

In 1669, or later, his experiments with distilled human urine resulted in the production of a glowing white substance, which he called "cold fire" (kaltes Feuer).

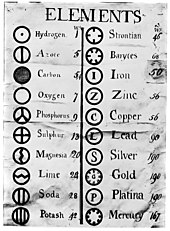

In 1808–10, British natural philosopher John Dalton published a method by which to arrive at provisional atomic weights for the elements known in his day, from stoichiometric measurements and reasonable inferences.

In 1860, the modern scientific consensus emerged at the first international chemical conference, the Karlsruhe Congress, and a revised list of elements and atomic masses was adopted.

[citation needed] In 1869, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev arranged 63 elements by increasing atomic weight in several columns, noting recurring chemical properties across them.

[34][a] Mendeleev continued to improve his ordering; in 1870, it gained a tabular shape, and each column was given its own highest oxide,[35] and in 1871, he further developed it and formulated what he termed the "law of periodicity".

That person is rightly regarded as the creator of a particular scientific idea who perceives not merely its philosophical, but its real aspect, and who understands so to illustrate the matter so that everyone can become convinced of its truth.

Compared to the rest of the work, Mendeleev's 1869 list misplaces seven then known elements: indium, thorium, and five rare-earth metals: yttrium, cerium, lanthanum, erbium, and didymium.

These elements (all thought to be divalent at the time) puzzled Mendeleev as they did not show a regular increase in valency despite their seemingly consequential atomic weights.

He measured the heat capacity of indium, uranium, and cerium to demonstrate their higher assumed valency (which was soon confirmed by Prussian chemist Robert Bunsen).

[56][f] In 1889, Mendeleev noted at the Faraday Lecture to the Royal Institution in London that he had not expected to live long enough "to mention their discovery to the Chemical Society of Great Britain as a confirmation of the exactitude and generality of the periodic law".

But a study of this arrangement, it must be allowed, is a somewhat tantalising pleasure; for, although the properties of elements do undoubtedly vary qualitatively, and, indeed, show approximate quantitative relations to their position in the periodic table, yet there are inexplicable deviations from regularity, which hold forth hopes of the discovery of a still more far-reaching generalisation.

[64] While the notion of a possibility of a group between that of halogens and that of alkali metals had existed (some scientists believed that several atomic weight values between halogens and alkali metals were missing, especially since places in this half of group VIII remained vacant),[65] argon did not easily match the position between chlorine and potassium because its atomic weight exceeded those of both chlorine and potassium.

[68] In 1896, Ramsay tested a report of American chemist William Francis Hillebrand, who found a stream of an unreactive gas from a sample of uraninite.

[69] Following this discovery, Ramsay, using fractional distillation to separate the components air, discovered several more such gases in 1898:[70] metargon, krypton, neon, and xenon; detailed spectroscopic analysis of the first of these demonstrated it was argon contaminated by a carbon-based impurity.

[77] Two weeks before that discussion, Belgian botanist Léo Errera had proposed to the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium to put those elements in a new group 0.

It was also believed that radioactive decay violated one of the central principles of the periodic table, namely that chemical elements could not undergo transmutations and always had unique identities.

Moseley, along with Charles Galton Darwin, Niels Bohr, and George de Hevesy, proposed that the nuclear charge (Z) might be mathematically related to physical properties.

[91] In 1913, amateur Dutch physicist Antonius van den Broek was the first to propose that the atomic number (nuclear charge) determined the placement of elements in the periodic table.

[92] With this, Moseley obtained the first accurate measurements of atomic numbers and determined an absolute sequence to the elements, allowing him to restructure the periodic table.

For example, his measurements of X-ray wavelengths enabled him to correctly place argon (Z = 18) before potassium (Z = 19), cobalt (Z = 27) before nickel (Z = 28), as well as tellurium (Z = 52) before iodine (Z = 53), in line with periodic trends.

[98] The chemist Charles Rugeley Bury made the next major step toward our modern theory in 1921, by suggesting that eight and eighteen electrons in a shell form stable configurations.

The elements from actinium to uranium were instead believed to form part of a fourth series of transition metals because of their high oxidation states; accordingly, they were placed in groups 3 through 6.

However, preliminary investigations of their chemistry suggested a greater similarity to uranium than to lighter transition metals, challenging their placement in the periodic table.

[111] During his Manhattan Project research in 1943, American chemist Glenn T. Seaborg experienced unexpected difficulties in isolating the elements americium and curium, as they were believed to be part of a fourth series of transition metals.

[110][113] In light of these observations and an apparent explanation for the chemistry of transuranic elements, and despite fear among his colleagues that it was a radical idea that would ruin his reputation, Seaborg nevertheless submitted it to Chemical & Engineering News and it gained widespread acceptance; new periodic tables thus placed the actinides below the lanthanides.

In the 1990s, Ken Czerwinski at University of California, Berkeley observed similarities between rutherfordium and plutonium and between dubnium and protactinium, rather than a clear continuation of periodicity in groups 4 and 5.

More recent experiments on copernicium and flerovium have yielded inconsistent results, some of which suggest that these elements behave more like the noble gas radon rather than mercury and lead, their respective congeners.