Normal mode

The free motion described by the normal modes takes place at fixed frequencies.

A physical object, such as a building, bridge, or molecule, has a set of normal modes and their natural frequencies that depend on its structure, materials and boundary conditions.

In the wave theory of physics and engineering, a mode in a dynamical system is a standing wave state of excitation, in which all the components of the system will be affected sinusoidally at a fixed frequency associated with that mode.

Because no real system can perfectly fit under the standing wave framework, the mode concept is taken as a general characterization of specific states of oscillation, thus treating the dynamic system in a linear fashion, in which linear superposition of states can be performed.

Each mode is characterized by one or several frequencies,[dubious – discuss] according to the modal variable field.

For a given amplitude on the modal variable, each mode will store a specific amount of energy because of the sinusoidal excitation.

In the analysis of conservative systems with small displacements from equilibrium, important in acoustics, molecular spectra, and electrical circuits, the system can be transformed to new coordinates called normal coordinates.

[1]: 332 Consider two equal bodies (not affected by gravity), each of mass m, attached to three springs, each with spring constant k. They are attached in the following manner, forming a system that is physically symmetric: where the edge points are fixed and cannot move.

The non trivial solutions are to be found for those values of ω whereby the matrix on the left is singular; i.e. is not invertible.

The general solution is a superposition of the normal modes where c1, c2, φ1, and φ2 are determined by the initial conditions of the problem.

In a standing wave, all the space elements (i.e. (x, y, z) coordinates) are oscillating in the same frequency and in phase (reaching the equilibrium point together), but each has a different amplitude.

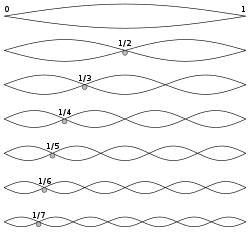

If the problem is bounded (i.e. it is defined on a finite section of space) there are countably many normal modes (usually numbered n = 1, 2, 3, ...).

In any solid at any temperature, the primary particles (e.g. atoms or molecules) are not stationary, but rather vibrate about mean positions.

In insulators the capacity of the solid to store thermal energy is due almost entirely to these vibrations.

Many physical properties of the solid (e.g. modulus of elasticity) can be predicted given knowledge of the frequencies with which the particles vibrate.

The simplest assumption (by Einstein) is that all the particles oscillate about their mean positions with the same natural frequency ν.

This is equivalent to the assumption that all atoms vibrate independently with a frequency ν. Einstein also assumed that the allowed energy states of these oscillations are harmonics, or integral multiples of hν.

The spectrum of waveforms can be described mathematically using a Fourier series of sinusoidal density fluctuations (or thermal phonons).

Thus, by replacing Einstein's identical uncoupled oscillators with the same number of coupled oscillators, Debye correlated the elastic vibrations of a one-dimensional solid with the number of mathematically special modes of vibration of a stretched string (see figure).

The normal modes of vibration of a crystal are in general superpositions of many overtones, each with an appropriate amplitude and phase.

Longer wavelength (low frequency) phonons are exactly those acoustical vibrations which are considered in the theory of sound.

In the longitudinal mode, the displacement of particles from their positions of equilibrium coincides with the propagation direction of the wave.

For transverse modes, individual particles move perpendicular to the propagation of the wave.

According to quantum theory, the mean energy of a normal vibrational mode of a crystalline solid with characteristic frequency ν is:

The waves in quantum systems are oscillations in probability amplitude rather than material displacement.

The frequency of oscillation, f, relates to the mode energy by E = hf where h is the Planck constant.

Thus a system like an atom consists of a linear combination of modes of definite energy.

For an elastic, isotropic, homogeneous sphere, spheroidal, toroidal and radial (or breathing) modes arise.

The degeneracy does not exist on Earth as it is broken by rotation, ellipticity and 3D heterogeneous velocity and density structure.

Modal cross-coupling occurs due to the rotation of the Earth, from aspherical elastic structure, or due to Earth's ellipticity and leads to a mixing of fundamental spheroidal and toroidal modes.