Caral–Supe civilization

[8] A 2001 paper in Science, providing a survey of the Caral research,[9] and a 2004 article in Nature, describing fieldwork and radiocarbon dating across a wider area,[2] revealed Caral–Supe's full significance and led to widespread interest.

[11][12] The discovery of Caral–Supe has also shifted the focus of research away from the highland areas of the Andes and lowlands adjacent to the mountains (where the Chavín, and later Inca, had their major centers) to the Peruvian littoral, or coastal regions.

Anthropologist Professor Winifred Creamer of Northern Illinois University notes that "when this civilization is in decline, we begin to find extensive canals farther north.

Ruth Shady highlights the links with the Kotosh Religious Tradition:[16] Numerous architectural features found among the settlements of Supe, including subterranean circular courts, stepped pyramids and sequential platforms, as well as material remains and their cultural implications, excavated at Aspero and the valley sites we are digging (Caral, Chupacigarro, Lurihuasi, Miraya), are shared with other settlements of the area that participated in what is known as the Kotosh Religious Tradition.

Most specific among these features include rooms with benches and hearths with subterranean ventilation ducts, wall niches, biconvex beads, and musical flutes.

Debate is ongoing regarding two related questions: the degree to which the flourishing of the Caral–Supe was based on maritime food resources, and the exact relationship this implies between the coastal and inland sites.

At Caral, the edible domesticated plants noted by Shady are squash, beans, lúcuma, guava, pacay (Inga feuilleei), and sweet potato.

Shady notes that "animal remains are almost exclusively marine" at Caral, including clams and mussels, and large amounts of anchovies and sardines.

[19][20] He confirmed a previously observed lack of ceramics at Aspero, and he deduced that "hummocks" on the site constituted the remains of artificial platform mounds.

[citation needed] This thesis of a maritime foundation was contrary to the general scholarly consensus that the rise of civilization was based on intensive agriculture, particularly of at least one cereal.

Moseley's ideas would be debated and challenged (that maritime remains and their caloric contribution were overestimated, for example),[21] but have been treated as plausible as late as 2005, when Mann conducted a summary of the literature.

They admitted the importance of agriculture to industry and to augment diet, while broadly affirming "the formative role of marine resources in early Andean civilization".

[1][22] However, Moseley wrote in 2004 that his hypothesis could be tested upon whether "the residents of Caral obtained more than 50% of their nutrition from the sea," using a dietary analysis of their bone chemistry.

Over time, seafood consumption at Caral appears to have decreased as advancements in agriculture and improved crop domestication provided a more scalable food source for the growing population compared to relying on wild fisheries.

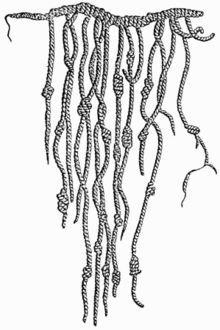

[24] The use of cotton (of the species Gossypium barbadense) played an important economic role in the relationship between the inland and the coastal settlements in this area of Peru.

New data drawn from coprolites, pollen records, and stone tool residues, combined with 126 radiocarbon dates, demonstrate that maize was widely grown, intensively processed, and constituted a primary component of the diet throughout the period from 3000 to 1800 BC.

[25] A somewhat later site, La Yerba III, on the other hand, was a permanently occupied settlement, and shows a population that was an order of magnitude greater than earlier.

[1] Haas suggests that the labour mobilization patterns revealed by the archaeological evidence, point to a unique emergence of human government, one of two alongside Sumer (or three, if Mesoamerica is included as a separate case).

[1] In exploring the basis of possible government, Haas suggests three broad bases of power for early complex societies:[citation needed] He finds the first two present in ancient Caral–Supe.

[citation needed] Economic authority would have rested on the control of cotton, edible plants, and associated trade relationships, with power centered on the inland sites.

Haas tentatively suggests that the scope of this economic power base may have extended widely: there are only two confirmed shore sites in the Caral–Supe (Aspero and Bandurria) and possibly two more, but cotton fishing nets and domesticated plants have been found up and down the Peruvian coast.

[13] Evidence regarding Caral–Supe religion is limited: in 2003, an image of the Staff God, a leering figure with a hood and fangs, was found on a gourd that dated to 2250 BC.

[23] The evidence of the development of complex government in the absence of warfare contrasts markedly to archaeological theory, which suggests that human beings move away from kin-based groups to larger units resembling "states" for mutual defense of often scarce resources.

In Caral–Supe, a vital resource was present: arable land generally, and the cotton crop specifically, but Mann noted that apparently, the move to greater complexity by the culture was not driven by the need for defense or warfare.

[citation needed] Evidence from the ground-breaking work during 1973 at Aspero, at the mouth of the Supe Valley, suggested a site of approximately 13 hectares (32 acres).

[9] In its summation of the 2001 Shady paper, the BBC suggests workers would have been "paid or compelled" to work on centralized projects of this sort, with dried anchovies possibly serving as a form of currency.

While visual arts appear absent, the people may have played instrumental music: thirty-two flutes, crafted from pelican bone, have been discovered.

The "monumental feud", as described by Archaeology, has included "public insults, a charge of plagiarism, ethics inquiries in both Peru and the United States, and complaints by Peruvian officials to the U.S.

[37] The lead author of the seminal paper of April 2001[9] was a Peruvian, Ruth Shady, with co-authors Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer, a married United States team; the co-authoring was reportedly suggested by Haas, in the hopes that the involvement of United States researchers would help secure funds for carbon dating as well as future research funding.

[43] In 2004, Haas et al. wrote that "Our recent work in the neighboring Pativilca and Fortaleza has revealed that Caral and Aspero were but two of a much larger number of major Late Archaic sites in the Norte Chico", while noting Shady only in footnotes.