North Carolina-class battleship

In planning a new battleship class in the 1930s, the US Navy was heavily constrained by international treaty limitations, which included a requirement that all new capital ships have a standard displacement of under 35,000 LT (35,600 t).

Eventually, the General Board of the United States Navy declared its preference for a battleship with a speed of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph), faster than any in US service, with a main battery of nine 14-inch (356 mm)/50 caliber Mark B guns.

After construction had begun, the United States invoked a so-called "escalator clause" in the international treaty to increase the class' main armament to nine 16-inch (406 mm)/45 caliber Mark 6 guns.

Both North Carolina and Washington saw extensive service during the Second World War in a variety of roles, primarily in the Pacific Theater where they escorted fast carrier task forces, such as during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and conducted shore bombardments.

"VII" returned to a lower speed to obtain more firepower (twelve 14-inch guns in triple turrets) and protection; as such, the design called for only 50,000 shp (37,000 kW)[C] and a length of only 640 ft (200 m).

Other problems included the design's defense against aircraft-dropped bombs, as the Bureau thought the formula used to calculate its effectiveness was not realistic, and the tapering of a fore bulkhead below the waterline could worsen underwater shell hits because the mostly unarmored bow could easily be penetrated.

These added an extra 11 feet (3.4 m) of length to "XVI" for greater speed, but the resulting weight increase meant that only eleven 14-inch guns could be mounted with a thin 10.1-inch (260 mm) belt.

The General Board liked "XVI-C" very much, seeing in it a ship that had enough protection to fight—and survive—in a battle line formed with the US' older battleships while also having enough speed to operate in a detached wing with aircraft carrier or cruiser commerce raiding groups.

Instead, he advocated a development of the previously rejected "XVI", adding additional underwater protection and patches of armor within the ship to make the magazines immune to above- and below-water shell hits from 19,000 yd (9.4 nmi; 17 km) and beyond.

After further revisions, Reeves went to Standley, the Chief of Naval Operations, who approved "XVI" in its newly modified form over the hopes of the General Board, who still thought that "XVI-C" should be built.

When figuring potential configurations for the North Carolinas, designers focused most of their planning on 14-inch weaponry; Standley's requirement meant that a switch from 14- to 16-inch, even after the ships' keels had been laid, was possible.

In a two-page letter to Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson and indirectly to Roosevelt, Reeves argued that the 16-inch gun's significantly greater armor penetration was of paramount importance, drawing examples from the First World War's Battle of Jutland, where some battleships were able to survive ten or twenty hits from large guns, but other battlecruisers were blown up in three to seven hits because the shells were able to cut through the armor protecting magazines and turrets.

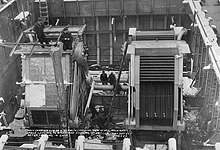

[38][39] The North Carolina class hull feature a bulbous bow and had an unusual stern design for the time by placing the two inboard propulsion shafts in skegs.

The ships' powerplant incorporated several recent developments in turbine equipment, including double helical reduction gears and high-pressure steam technology.

[55][56] Construction of the North Carolina class was slowed by the aforementioned material issues, the changes made to the basic design after this date—namely the substitution of 16-inch for 14-inch guns—and the need to add both length and strength to the slipways already present in the navy yards.

A problem shared with its sister Washington and some other ships like Atlanta, it was only cured after different propellers were tested aboard North Carolina, including four-bladed and cut-down versions of the original three-bladed.

[58][61][62][63] Repaired and refitted at the facilities in Pearl Harbor, North Carolina operated as a carrier escort for Enterprise and Saratoga for the remainder of 1942 and the majority of 1943 while they provided cover for supply and troop movements in the Solomons.

[58][64] Joining Task Force 58 in January 1944, North Carolina escorted aircraft carriers as the flagship of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee, Commander, Battleships, Pacific Fleet (ComBatPac) for much of the year, providing support for airborne strikes on Kwajalein, Namur, Truk (twice), Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Palau, Woleai, and Hollandia in January–April.

With repairs completed, the battleship joined with Enterprise on 6 June for assaults within the Marianas; as part of these, North Carolina used its main battery to bombard Saipan and Tanapag.

Surviving another typhoon, one which sank three destroyers, North Carolina continued escort duty when naval aircraft struck Formosa, Indo-China, China, the Ryukyus and Honshu in January and February 1945.

After receiving another overhaul from 9 May to 28 June, this one in the naval yard at Pearl Harbor, North Carolina operated as both a carrier escort and shore bombardier for the remainder of the war.

Of note was a 17 July bombardment of the industrial area in Hitachi, Ibaraki in company with fellow battleships Alabama, Missouri, Wisconsin and HMS King George V, along with smaller warships.

Although commissioned, its engine had not yet been run at full power—like its sister, Washington had major problems with longitudinal vibrations, which were only tempered after many tests conducted aboard North Carolina.

On 4 June, Washington hosted the commander of US naval forces in Europe, Admiral Harold Rainsford Stark, who set up a temporary headquarters on the ship for the next few days.

[68][70][71] Washington left the North Sea bound for the United States on 14 July with an escort of four destroyers; upon arrival at the New York Naval Yard on the 23rd, it was given a full overhaul which took a month to be completed.

It set sail for the Panama Canal and the Pacific Ocean on 23 August and reached its destination, Tonga Island, on 14 September, where it became the flagship of Admiral Willis "Ching" Lee.

Departing in late November, Washington first steamed to Makin to provide protection for ships there, then Ocean Island to prepare to bombard Nauru with its sister North Carolina, all four South Dakota-class battleships, and the carriers Bunker Hill and Monterey.

After temporary reinforcements to the damaged section, it was forced to sail to Pearl Harbor to be fitted with a false bow to make possible a voyage to Puget Sound.

[48][68][78][79] Washington next participated in the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, serving again as a carrier escort ship, though it was detached on the 13th to fire on Japanese positions on Saipan and Tinian.

[4][68][80][81][82][G] North Carolina and Washington remained in active duty in the years immediately after the war, possibly because their crew accommodations were more comfortable and less cramped than the four South Dakotas.