Northern crested newt

Although today the most widespread Triturus species, the northern crested newt was probably confined to small refugial areas in the Carpathians during the Last Glacial Maximum.

While the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists it as Least Concern species, populations of the northern crested newt have been declining.

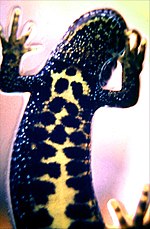

[9] The newts have rough skin, and are dark brown on the back and sides, with black spots and heavy white stippling on the flanks.

The throat is mixed yellow–black with fine white stippling, the belly yellow to orange with dark, irregular blotches.

The northern edge of its range runs from Great Britain through southern Fennoscandia to the Republic of Karelia in Russia; the southern margin runs through central France, southwest Romania, Moldavia and Ukraine, heading from there into central Russia and through the Ural Mountains.

The eastern extent of the great crested newt's range reaches into Western Siberia, running from the Perm Krai to the Kurgan Oblast.

[10] In western France, the species co-occurs and sometimes hybridises (see section Evolution below) with the marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus).

In the absence of forests, other cover-rich habitats, as for example hedgerows, scrub, swampy meadows, or quarries, can be inhabited.

[8]: 47–48,76 [12][10] Preferred aquatic breeding sites are stagnant, mid- to large-sized, unshaded water bodies with abundant underwater vegetation but without fish (which prey on larvae).

[8]: 48 Examples of other suitable secondary habitats are ditches, channels, gravel pit lakes, or garden ponds.

The aquatic phase serves not only for reproduction, but also offers more abundant prey, and immature crested newts frequently return to the water in spring even if they do not breed.

[8]: 52–58 During the terrestrial phase, the newts use hiding places such as logs, bark, planks, stone walls, or small mammal burrows; several individuals may occupy such refuges at the same time.

Since the newts generally stay very close to their aquatic breeding sites, the quality of the surrounding terrestrial habitat largely determines whether an otherwise suitable water body will be colonised.

[8]: 47–48,76 [12][14] Great crested newts may also climb vegetation during their terrestrial phase, although the exact function of this behaviour is not known at present.

The newts do not migrate very far: they may cover around 100 metres (110 yd) in one night and rarely disperse much farther than one kilometre (0.62 mi).

During the land phase, prey include earthworms and other annelids, different insects and their larvae, woodlice, and snails and slugs.

[8]: 78 They secrete the poison tetrodotoxin from their skin, albeit much less than for example the North American Pacific newts (Taricha).

[18] The bright yellow or orange underside of crested newts is a warning coloration which can be presented in case of perceived danger.

[8]: 79 Northern crested newts, like their relatives in the genus Triturus, perform a complex courtship display, where the male attracts a female through specific body movements and waves pheromones to her.

Their limited dispersal makes the newts especially vulnerable to fragmentation, i.e. the loss of connections for exchange between suitable habitats.

[12] Other threats include the introduction of fish and crayfish into breeding ponds,[12] collection for the pet trade in its eastern range,[12] warmer and wetter winters due to global warming,[8]: 110 genetic pollution through hybridisation with other, introduced crested newt species,[20] the use of road salt,[27] and potentially the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans.

[30] As required by these frameworks, its capture, disturbance, killing or trade, as well as the destruction of its habitats, are prohibited in most European countries.

[12] Preservation of natural water bodies, reduction of fertiliser and pesticide use, control or eradication of introduced predatory fish, and the connection of habitats through sufficiently wide corridors of uncultivated land are seen as effective conservation actions.

In some cases, entire populations have been moved when threatened by development projects, but such translocations need to be carefully planned to be successful.