Triturus

Although not immediately threatened, crested and marbled newts suffer from population declines caused mainly by habitat loss and fragmentation.

The monophyly of the genus Triturus in the strict sense is supported by molecular data[1] and synapomorphies such as a genetic defect causing 50% embryo mortality (see below, Egg deposition and development).

Substantial genetic differences between subspecies were, however, noted and eventually led to their recognition as full species, with the crested newts often collectively referred to as "T. cristatus superspecies".

[7] These types were first noted by herpetologist Willy Wolterstorff, who used the ratio of forelimb length to distance between fore- and hindlimbs to distinguish subspecies of the crested newt (now full species); this index however sometimes leads to misidentifications.

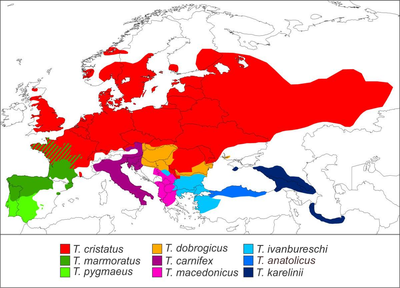

[4] Triturus newts occupy distinct geographical regions (see Distribution), but hybrid forms occur at range borders between some species and have intermediate characteristics (see Hybridisation and introgression).

[8]: 98–99 The aquatic habitats preferred by the newts are stagnant, mid- to large-sized, unshaded water bodies with abundant underwater vegetation but without fish, which prey on larvae.

[8]: 48 Examples of other suitable secondary habitats are ditches, channels, gravel pit lakes, garden ponds, or (in the Italian crested newt) rice paddies.

The Danube crested newt is more adapted to flowing water and often breeds in river margins, oxbow lakes or flooded marshland, where it frequently co-occurs with fish.

The aquatic phase serves not only for reproduction, but also offers the animals more abundant prey, and immature crested newts frequently return to the water in spring even if they do not breed.

[8]: 52–58 [9]: 142–147 During their terrestrial phase, crested and marbled newts depend on a landscape that offers cover, invertebrate prey and humidity.

Within such habitats, the newts use hiding places such as logs, bark, planks, stone walls, or small mammal burrows; several individuals may occupy such refuges at the same time.

Since the newts in general stay very close to their aquatic breeding sites, the quality of the surrounding terrestrial habitat largely determines whether an otherwise suitable water body will be colonised.

[18] The bright yellow or orange underside of crested newts is a warning coloration which can be presented in case of perceived danger.

A position characteristic for the large Triturus species is the "cat buckle", where the male's body is kinked and often rests only on the forelegs ("hand stand").

The female deposits them individually on leaves of aquatic plants, such as water cress or floating sweetgrass, usually close to the surface, and, using her hindlegs, folds the leaf around the eggs as protection from predators and radiation.

In the first days after hatching, they live on their remaining embryonic yolk supply and are not able to swim, but attach to plants or the egg capsule with two balancers, adhesive organs on their head.

Just before the transition to land, the larvae resorb their external gills; they can at this stage reach a size of 7 centimetres (2.8 in) in the larger species.

[8]: 11 Triturus species usually live at low elevation; the Danube crested newt for example is confined to lowlands up to 300 m (980 ft) above sea level.

The origin of current-day species is not fully understood so far, but one hypothesis suggests that ecological differences, notably in the adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle, may have evolved between populations and led to parapatric speciation.

[10][27] Alternatively, the complex geological history of the Balkan peninsula may have further separated populations there, with subsequent allopatric speciation and the spread of species into their current ranges.

A study using environmental niche modelling and phylogeography showed that during the Last Glacial Maximum, around 21,000 years ago, crested and marbled newts likely survived in warmer refugia mainly in southern Europe.

Today's most widespread species, the northern crested newt, was likely confined to a small refugial region in the Carpathians during the last glaciation, and from there expanded its range north-, east- and westwards when the climate rewarmed.

Hybridisation does occur in several of these contact zones, as shown by genetic data and intermediate forms, but is rare, supporting overall reproductive isolation.

This concerns especially breeding sites, which are lost through the upscaling and intensification of agriculture, drainage, urban sprawl, and artificial flooding regimes (affecting in particular the Danube crested newt).

Especially in the southern ranges, exploitation of groundwater and decreasing spring rain, possibly caused by global warming, threaten breeding ponds.

Introduction of crayfish and predatory fish threatens larval development; the Chinese sleeper has been a major concern in Eastern Europe.

Exotic plants can also degrade habitats: the swamp stonecrop replaces natural vegetation and overshadows waterbodies in the United Kingdom, and its hard leaves are unsuitable for egg-laying to crested newts.

[9]: 106–110 [13] Land habitats, equally important for newt populations, are lost through the replacement of natural forests by plantations or clear-cutting (especially in the northern range), and the conversion of structure-rich landscapes into uniform farmland.

[32] Warmer and wetter winters due to global warming may increase newt mortality by disturbing their hibernation and forcing them to expend more energy.

This includes preservation of natural water bodies, reduction of fertiliser and pesticide use, control or eradication of introduced predatory fish, and the connection of habitats through sufficiently wide corridors of uncultivated land.