Northumbria

Northumbria (/nɔːrˈθʌmbriə/; Old English: Norþanhymbra rīċe [ˈnorˠðɑnˌhymbrɑ ˈriːt͡ʃe]; Latin: Regnum Northanhymbrorum)[2] was an early medieval Anglian kingdom in what is now Northern England and South Scotland.

Moreover, Brian Hope-Taylor has traced the origins of the name Yeavering, which looks deceptively English, back to the British gafr from Bede's mention of a township called Gefrin in the same area.

[17] The name that these two states eventually united under, Northumbria, might have been coined by Bede and made popular through his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

[18] Information on the early royal genealogies for Bernicia and Deira comes from Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People and Nennius' Historia Brittonum.

[25] While violent conflicts between Bernicia and Deira played a significant part in determining which line ultimately gained supremacy in Northumbria, marriage alliances also helped bind these two territories together.

The second intermarriage was more successful, with Oswiu marrying Edwin's daughter and his own cousin Eanflæd to produce Ecgfrith, the beginning of the Northumbrian line.

Although primarily recorded in the southern provinces of England, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (particularly the D and E recensions) provide some information on Northumbria's conflicts with Vikings in the late eighth and early ninth centuries.

The E recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests that Northumbria was particularly vulnerable at this time because the Northumbrians were once again fighting amongst themselves, deposing Osberht in favour of Ælle.

[29] In Northumbria, the Norse established the Kingdom of York whose boundaries were roughly the River Tees and the Humber, giving it approximately the same dimensions as Deira.

[36] The political landscape of the area north of the Tees during the Viking conquest of Northumbria consisted of the Community of St. Cuthbert and the remnants of the English Northumbrian elites.

The land extended from the Tees to the Tyne and anyone who fled there from either the north or the south would receive sanctuary for thirty-seven days, indicating that the Community of St. Cuthbert had some juridical autonomy.

Based on their positioning and this right of sanctuary, this community probably acted as a buffer between the Norse in southern Northumbria and the Anglo-Saxons who continued to hold the north.

Oswiu succeeded where Edwin and Oswald failed as, in 655, he slew Penda during the Battle of the Winwaed, making him the first Northumbrian King also to control the kingdom of Mercia.

[53] During his reign, he presided over the Synod of Whitby, an attempt to reconcile religious differences between Roman and Celtic Christianity, in which he eventually backed Rome.

Æthelstan is widely considered one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings for his efforts to consolidate the English kingdom and the prosperity his reign brought.

After the English from Wessex absorbed the Danish-ruled territories south of the Tees, Scots invasions reduced the rump Northumbria to an earldom stretching from the Tyne to the Tweed.

[72] After the Romans left Britain in the early fifth century, Christianity did not disappear,[73] but it existed alongside Celtic paganism,[74] and possibly many other cults.

[93] During the ninth and tenth centuries, there was an increase in the number of parish churches, often including stone sculptures incorporating Scandinavian designs.

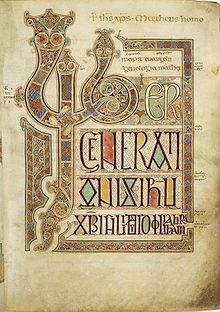

The Irish monks who converted Northumbria to Christianity, and established monasteries such as Lindisfarne, brought a style of artistic and literary production.

[95] The Irish monks brought with them an ancient Celtic decorative tradition of curvilinear forms of spirals, scrolls, and doubles curves.

This style was integrated with the abstract ornamentation of the native pagan Anglo-Saxon metalwork tradition, characterized by its bright colouring and zoomorphic interlace patterns.

[96] Insular art, rich in symbolism and meaning, is characterized by its concern for geometric design rather than naturalistic representation, love of flat areas of colour, and use of complicated interlace patterns.

[99] It heralded the end of Northumbria's position as a centre of influence, although in the years immediately following visually rich works like the Easby Cross were still being produced.

His Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) has become both a template for later historians and a crucial historical account in its own right,[100] and much of it focuses on Northumbria.

According to Bede, he "was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in English, which was his native language.

By the early 900s, however, Scandinavian-style names for both people and places became increasingly popular, as did Scandinavian ornamentation on works of art, featuring aspects of Norse mythology, and figures of animals and warriors.

Nevertheless, sporadic references to "Danes" in charters, chronicles, and laws indicate that during the lifetime of the Kingdom of Northumbria, most inhabitants of northeast England did not consider themselves Danish, and were not perceived as such by other Anglo-Saxons.

[111] The Gosforth Cross, dated to the early tenth century, stands at 14 feet (4.4 m) and is richly decorated with carvings of mythical beasts, Norse gods, and Christian symbolism.

When coinage (as opposed to bartering) regained popularity in the late 600s, Northumbrian coins featured kings' names, indicating royal control of currency.

[127] Analysis of written texts, brooches, runes and other available sources shows that Northumbrian vowel pronunciation differed from West Saxon.