Norwegian language conflict

As a result, the proximity of modern written Norwegian to Danish underpins controversies in anti-imperialistic nationalism, rural versus urban cultures, literary history, diglossia (colloquial and formal dialects, standard language), spelling reform, and orthography.

After the Treaty of Kiel transferred Norway from Denmark–Norway to Sweden–Norway in 1814, Dano-Norwegian (or "det almidelige bogmaal") was the sole official language until 1885 when Ivar Aasen's Landsmaal gained recognition.

The government attempted over several decades to bring the two language forms closer to each other with the goal of merging them but failed due to widespread resistance from both sides.

The now-abandoned official policy to merge Bokmål and Nynorsk into one written standard called Samnorsk through a series of reforms has created a wide spectrum of varieties of the two.

The Norwegian-born writer Ludvig Holberg became one of the leading exponents of standard written Danish, even as he retained a few distinctly Norwegian forms in his own writing.

Examples include Petter Dass, Johan Nordahl Brun, Jens Zetlitz, and Christian Braunmann Tullin.

åk Vilken av så mange ær dæn Fårnuftigste?—utilized many of his at-the-time controversial linguistic ideas, which included phonemic orthography, using the feminine grammatical gender in writing, and the letter ⱥ (a with a slash through it, based on ø) to replace aa.

It was forced into a new, but weaker, union with Sweden, and the situation evolved into what follows: The dissolution of Denmark–Norway occurred in the era of the emerging European nation states.

Henrik Wergeland may have been the first to do so; but it was the collected folk tales by Jørgen Moe and Peter Christen Asbjørnsen that created a distinct Norwegian written style.

Though most of these terms were probably taken straight from Aasmund Olavsson Vinje's travel accounts, the publication reflected a widespread recognition that much written Norwegian no longer was pure Danish.

Knud Knudsen, a teacher, worked instead to adapt the orthography more closely to the spoken Dano-Norwegian koiné known as "cultivated daily speech" (dannet dagligtale).

He argued that the cultivated daily speech was the best basis for a distinct Norwegian written language, because the educated classes did not belong to any specific region, they were numerous, and possessed cultural influence.

Such orthographic reforms continued in subsequent years, but in 1892 the Norwegian department of education approved the first set of optional forms in the publication of Nordahl Rolfsen's Reader for the Primary School (Læsebog for Folkeskolen).

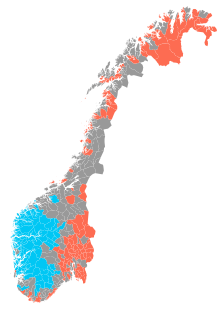

Also, in 1892, national legislation gave each local school board the right to decide whether to teach its children Riksmål or Landsmål.

The play culminates in the Landsmål proponents killing each other over what to call their country: Noregr, Thule, Ultima, Ny-Norig, or Nyrig.

The greatest controversy erupted over the city of Trondheim, which had until then been known as Trondhjem, but in the Middle Ages era had been called Nidaros.

A teacher, Knut Grimstad, refused to accept this on the grounds that neither the school district nor the Norwegian national authorities had the right to impose a version of a spoken language as instruction.

Olav Andreas Eftestøl (1863-1930), the school director for this region—there were seven such appointees for the entire country—took this decision to the department in 1924, and another parliamentary debate ensued.

Having already changed the names of the languages—Riksmål became Bokmål and Landsmål Nynorsk—by parliamentary resolution of 1929, the Labour party made Koht their thought leader and spokesperson on these issues, formalizing his views into their platform.

In particular, the proponents of Riksmål felt the reforms were a frontal assault on their written language and sensibilities, since many elements of their previous norm—dannet dagligtale—were deprecated.

On the other side of the issue, the poet Arnulf Øverland galvanized Riksmålsforbundet in opposition not to Nynorsk, which he respected, but against the radical Bokmål recommended by the 1938 reforms.

Their efforts were particularly noted in Oslo, where the school board had decided to make radical forms of Bokmål the norm in 1939 (Oslo-vedtaket).

As a government agency (and monopoly) that has traditionally been strongly associated with the Nynorsk-supporting Norwegian Labour Party, NRK was required to include both languages in its broadcasts.

Still, the Riksmål advocates were outraged, since they noted that some of the most popular programs (such as the 7 pm news) were broadcast in Nynorsk, and the Bokmål was too radical in following the 1938 norms.

However, Smebye was effectively disallowed from performing on television and ended up suing and prevailing over NRK in a supreme court case.

Double consonants to denote short vowels are put in common use; the silent "h" is eliminated in a number of words; more "radical" forms in Bokmål are made primary; while Nynorsk actually offers more choices.

At the universities, students were encouraged to "speak their dialect, write Nynorsk", and radical forms of Bokmål were adopted by urban left-wing socialists.

In 1973, Norsk språkråd instructed teachers to no longer correct students who used conservative Riksmål in their writing, provided these forms were used consistently.

On 13 December 2002 the Samnorsk ideal was finally officially abandoned when the Ministry of Culture and Church affairs sent out a press release to that effect.

[13] There is further a concern in some quarters that poor grammar and usage is becoming more commonplace in the written press and broadcast media, and consequently among students and the general population.