Nuclear and radiation accidents and incidents

A nuclear and radiation accident is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "an event that has led to significant consequences to people, the environment or the facility."

[citation needed] A study published in 2005 by the World Health Organization estimates that there may eventually be up to 4,000 additional cancer deaths related to the accident among those exposed to significant radiation levels.

[27][28] Social scientist and energy policy expert, Benjamin K. Sovacool has reported that worldwide there have been 99 accidents at nuclear power plants from 1952 to 2009 (defined as incidents that either resulted in the loss of human life or more than US$50,000 of property damage, the amount the US federal government uses to define major energy accidents that must be reported), totaling US$20.5 billion in property damages.

[45] The United States 9/11 Commission found that nuclear power plants were potential targets originally considered as part of the September 11 attacks.

Non-proliferation policy experts have questioned "the use of private contractors to provide security at facilities that manufacture and store the government's most dangerous military material".

Stuxnet is a computer worm discovered in June 2010 that is believed to have been created by the United States and Israel to attack Iran's nuclear facilities.

The International Atomic Energy Agency says there is "a persistent problem with the illicit trafficking in nuclear and other radioactive materials, thefts, losses and other unauthorized activities".

In a smaller scale accident at Sarov a technician working with highly enriched uranium was irradiated while preparing an experiment involving a sphere of fissile material.

The Sarov accident is interesting because the system remained critical for many days before it could be stopped, though safely located in a shielded experimental hall.

The main cause of the release of radioactivity in the Three Mile Island accident was a pilot-operated relief valve on the primary loop which stuck in the open position.

[130] An assessment conducted by the Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique (CEA) in France concluded that no amount of technical innovation can eliminate the risk of human-induced errors associated with the operation of nuclear power plants.

[10] In 1946 Canadian Manhattan Project physicist Louis Slotin performed a risky experiment known as "tickling the dragon's tail"[131] which involved two hemispheres of neutron-reflective beryllium being brought together around a plutonium core to bring it to criticality.

The screwdriver slipped and set off a chain reaction criticality accident filling the room with harmful radiation and a flash of blue light (caused by excited, ionized air particles returning to their unexcited states).

Slotin reflexively separated the hemispheres in reaction to the heat flash and blue light, preventing further irradiation of several co-workers present in the room.

The best known example of this type of event is the 1987 Goiânia accident in Brazil, when a radiotherapy source was forgotten and abandoned in a hospital, to be later stolen and opened by scavengers.

A similar case occurred in 2000 in Samut Prakan, Thailand when the radiation source of an expired teletherapy unit was sold unregistered, and stored in an unguarded car park from which it was stolen.

[145] In his book Normal Accidents, Charles Perrow says that unexpected failures are built into society's complex and tightly coupled nuclear reactor systems.

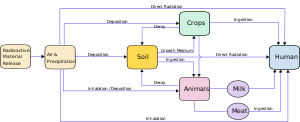

The long-term detrimental effects on agriculture, farming, and livestock, can potentially affect human health and safety long after the actual event.

In 2013, contaminated groundwater was found in between some of the affected turbine buildings in the Fukushima Daiichi facility, including locations at bordering seaports on the Pacific Ocean.

[157] Along the same coastline, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) found trace amounts of Fukushima contaminates 100 miles (150 km) off the coast of Eureka, California in November 2014.

[156] Despite the relatively dramatic increases in radiation, the contamination levels still satisfy the World Health Organization's (WHO's) standard for clean drinking water.

[158] Multiple private agencies as well as various North American governments monitor the spread of radiation throughout the Pacific to track the potential hazards it can introduce to food systems, groundwater supplies, and ecosystems.

Due to the violent nature of the accident there, a sizable portion of the resulting radioactive contamination of the atmosphere consisted of particles that were dispersed during the explosion.

Radionuclides carried by groundwater systems have resulted in the uptake of radioactive material in plants and then up the food chains into animals, and eventually humans.

In Belarus, just north of Chernobyl, about 250,000 hectares of previously usable farmland were held[clarification needed] by state officials until deemed safe.

Partially due to the already abandoned urban areas, as well as international relations currently affecting the country, remediation efforts have minimized[clarification needed] compared to the initial clean up actions and more recent accidents such as the Fukushima incident.

Notably, residents of Koyan showcased physical adaptation to the pervasive radiation, exhibiting resilience in their home environment, coupled with experiences of illness when outside it.

[169] Stawkowski's primary assertion revolves around the concept of "slow violence," portraying the subjects as resilient human beings who, despite the inevitability of illness in many families, have managed to lead long lives.

While the historical context may lead Westerners to scrutinize political and scientific research during the Soviet Union era, the residents and neighboring villages represent a lasting legacy.

The secrecy enveloping the Soviet nuclear project restricted researchers' access to data on released radioisotopes, unlike their United States counterparts, who could trace them in the environment.